During a February 2009 Lace Forum at Lacis of Berkeley, California, where I was teaching classes in knitted lace, a participant, Teresa Mize, showed me a lace shawl belonging to her mother, Cherie Martineau Helm. Cherie, a textile collector, had purchased it in the late 1990s at the Treasure Market, a benefit for Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center. Although no documentation accompanied the shawl, Cherie recognized it as a special piece, perhaps of Russian origin. Teresa hoped that I could confirm its origin. People often approach me regarding a lace piece that they are convinced has a Russian connection, but more often than not, the piece is not Russian or is Russian but of poor quality.

When I saw Cherie’s shawl, I realized immediately that I was in the presence of a historic artifact; several characteristics pointed unquestionably to its origin in Orenburg, Russia, the birthplace of a distinctive style of knitted-lace shawls. Certain construction methods and the use of a two-ply yarn made from the down of Orenburg goats combined with silk dated the shawl to between 1880, when the down-silk yarn first came into use in the region, and 1917, just before the Russian Revolution, when the Orenburg knitting community stopped producing this type of shawl.

Left: Raveling the fringe of the circa 1880–1917 shawl. Fiber from the fringe was used to repair the holes in the shawl. Right: Pieces of the fiber removed from the fringe of the circa 1880–1917 shawl. Photos of shawl during repair courtesy of Galina Khmeleva

For its age, the shawl was in remarkably good condition, but it had a number of noticeable holes and discolored areas. I was well aware of the difficulties inherent in working with such a delicate fabric, but following discussions with Teresa, I agreed to repair the damaged areas to the best of my ability, documenting each step of the process with photographs.

Back in my studio in Fort Collins, Colorado, I examined the shawl more closely and found four large holes; twenty-two smaller holes; two large areas where the down fiber had disintegrated, leaving just the silk ply; several areas where threads were broken and/or pulled out; and six areas that appeared to be stained with tea, coffee, or perfume.

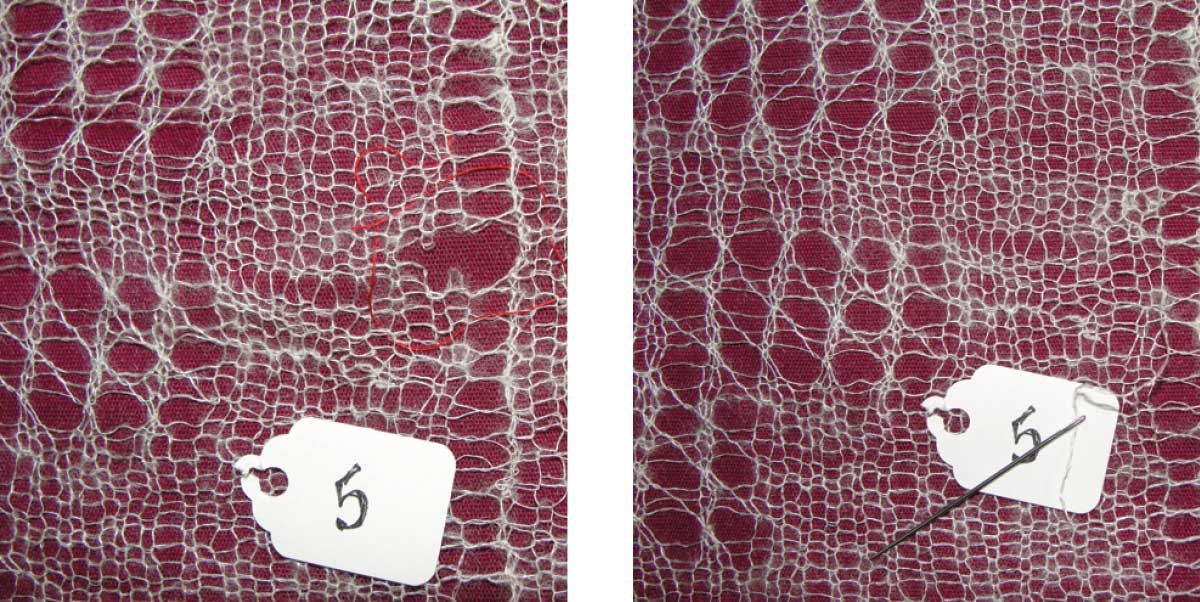

Left: A hole in the circa 1880–1917 shawl outlined with red thread. Right: The area of the circa 1880–1917 shawl with the hole in the final stages of repair.

During my many years in the textile business, I have accumulated a large collection of fibers from around the world. I considered spinning the fiber that best matched the color and micron count of the original and plying the resulting singles with antique silk from Uzbekistan, but reading Maggie Petsch’s “Repairing Mama’s Crocheted Tablecloth” (PieceWork, November/December 2007) changed my mind: I realized that a suitable restoration necessitated using the same materials as those used in the original shawl. But where could I find original materials for a shawl knitted in Russia more than 100 years ago?

Right: Tools used to repair the circa 1880–1917 shawl. The antique Russian crochet hook is from the author’s collection. Left: The repair of the circa 1880–1917 shawl in progress in the author’s studio.

Another assessment of the shawl revealed that the solution was right in front of me: I could use yarn from the knitted fringe that was attached with cotton thread to the top and bottom of the shawl. Carefully removing the cotton thread, I began to ravel the fringe fiber into usable fragments of individual threads; the longest measured about 12 inches (30 cm) long. I straightened the fibers by moistening them with water and spreading them out on a piece of cotton fabric to dry. I outlined each hole with red thread. Using a tapestry needle, crochet hook, and countless T-pins, and beginning about 1½ inches (4 cm) outside the edges of each hole, I used duplicate stitch to replicate the pattern of the area. After repairing all the holes, I reattached the fringe to the top and bottom of the shawl. I carefully dabbed a cotton cloth moistened with a mild soap solution on the discolored areas. It was many, many hours before I completed the project, truly a labor of love for me. Now that it is restored, Cherie Helm plans to donate this magnificent example of Orenburg lace knitting to The Lace Museum in Sunnyvale, California.

Galina A. Khmeleva is the owner of Skaska Designs and author of two books about the history and techniques of Orenburg lace shawls.

This article was published in the May/June 2011 issue of PieceWork.