Historical records from the distant past don’t say much about women, and they say even less about women’s everyday lives. Yet every now and then we get fleeting glimpses of the history of textiles. In this series of posts, (see parts one and two), I’ll share tidbits about textiles and the women who made them, gathered from my years of teaching early world history at the college level. I’ll focus mostly on European and Mediterranean cultures (the ones I know best), and on weaving and spinning until knitting emerged in the 13th century and crochet developed in the 19th century.

Pottery from Athens

Historians and archeologists have a hard time studying the ancient world, and they really run into trouble trying to understand women’s lives in antiquity because sources haven’t survived very well. Fortunately, Athens left behind valuable—if ambiguous—clues to women’s roles and family life on its decorated pottery. Like their contemporaries around the world, Athenians stored food, water, wine, oil, perfume, and other items in clay vessels. They also used pottery for special occasions such as funerals, men’s drinking parties (called symposia), and weddings. Potters in the city-states of Greece painted clay vessels with beautiful images that often told stories or jokes.

Painted vases from Athens in particular became popular around the Mediterranean, and starting in the 8th century BCE, the city-state made a lot of money exporting them. In fact, one neighborhood of Athens, the Kerameikos (or Ceramicus in Latin) took its name from the Greek word for clay because potters worked there. (Yes, it’s the source of the English word “ceramic.”) Archeologists have excavated vast quantities of pottery—shards from painted vessels, intact pots, and undecorated shipping jars—made in the Kerameikos and either used in Athens or exported to another city in the Mediterranean.

Every bit of pottery can reveal something about Athenian society, trade, and/or private life. The fine decorated vessels are especially informative because different pot shapes served unique functions. When we consider the vessel’s shape and its painting, we can see how Athenians expected different members of society to behave. For instance, the painting on a drinking cup for an all-male drinking party looked very different from the decorations on a bride’s wedding vase.

Not Just Gender: Women’s Roles in Athens

In every human culture, social expectations of men and women rest on multiple factors, not just the person’s biological sex. There’s no way to compare the roles of all women to all men, or to compare women’s status in different societies or over time. Biological sex, social status, race or ethnicity, and age all mattered in Athens, no matter how the city-state was governed. It’s why historians can’t give a simple answer to questions like “What was the status of women in democratic Athens?” or “Did women have more status in Athens or in the rival city-state of Sparta?”

Historian Sarah B. Pomeroy has proposed that Athenian culture typically categorized mortal women in 3 ways (I’m not counting goddesses):

- Respectable wives and daughters of citizen men. These women had lots of protection but very little independence, and they could lose their respectability from mere rumors of bad behavior. For instance, when they went outside the home, they were expected to travel in pairs or groups to protect their bodies and their reputations.

- Sex workers, from expensive high-class courtesans down to the cheapest prostitutes called pornai—the root of the English word “pornography.” These women could have lots of independence but little protection. They could never become respectable, yet because Athenian society saw them as necessary, they could exercise lots of influence over important men in the city-state. It’s also worth noting that a culture that values “good girls” has to have “bad girls” for contrast.

- Slave women, who performed household tasks inside and outside of the dwelling place. They generally came under the household’s protection in exchange for giving up bodily autonomy. Not only did they perform errands outside of the home, they might be expected to sleep with members of the household or its honored guests.

Women on Pots

Of these three groups, respectable women and sex workers show up most frequently on Athenian pottery. We see respectable wives and daughters on jars made for weddings or women’s everyday needs. These pots seem to have encouraged women to love their husbands, make fabric, and look good doing it. For instance, the oil jar on the left depicts Eros, the god of love, visiting a seated woman. You can just see her wool basket, called a kalathos, behind her. On the jar at lower right, a woman admires her clothing in a mirror as she stands next to her wool basket; by implication, she wove the fabric she wears. Finally, on the leg guard at upper right, women prepare wool for spinning. Leg guards were made from terra-cotta, and while scholars aren’t exactly certain how they were used, there’s evidence that women used leg guards while carding wool. The guard fit over a woman’s knee and lower thigh; scratches and wear on the outer surface of surviving artifacts suggest that it would protect the woman’s leg from many a painful brush with the carder’s working surface. I might need to commission a leg guard for myself before my next fiber prep session!

Left: On an oil jar made around 480–470 BCE, a woman greets Eros as she sits next to her wool basket. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1906. Lower right: A woman stands next to her wool basket as she looks at her reflection in a mirror, on jar from about 480–470 BCE. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchased by subscription, 1896. Upper right: A leg guard showing women preparing wool for spinning. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1910

Another very famous oil jar depicts every stage of clothmaking, from fiber prep to weaving.

An oil jar from about 550–530 BCE shows women weighing wool (left), weaving fabric on an upright loom (center), and folding finished cloth and spinning yarn for weaving (right). Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fletcher Fund, 1931

It’s clear from the examples above that vase painters (or their patrons) appreciated respectable wives who fulfilled their household duties. We don’t know whether the painters meant to portray women’s lives realistically or simply to teach a lesson about what was expected of women, but there’s little to no sense of mockery in these depictions.

The same cannot be said of vase paintings that showed sex workers. Nearly any time you see a nude woman on Athenian pottery, you can be sure that scholars haven’t quite agreed on an interpretation.

There are only a few clear-cut examples where a particular painting seems to be advertising the sex worker’s services or telling men what to expect at a drinking party. Pottery used exclusively at men’s drinking parties tells us a lot about gender roles, especially for wealthier men of Athens’ citizen class. The host and guests were all free males, waited on by the host’s male or female household slaves. Any other women in attendance came to entertain the men in one way or another, so they fell into the “bad girls” category—even if they came to sing, dance, play the flute, recite poetry, or converse about philosophy rather than offering physical delights, they were never respectable women.

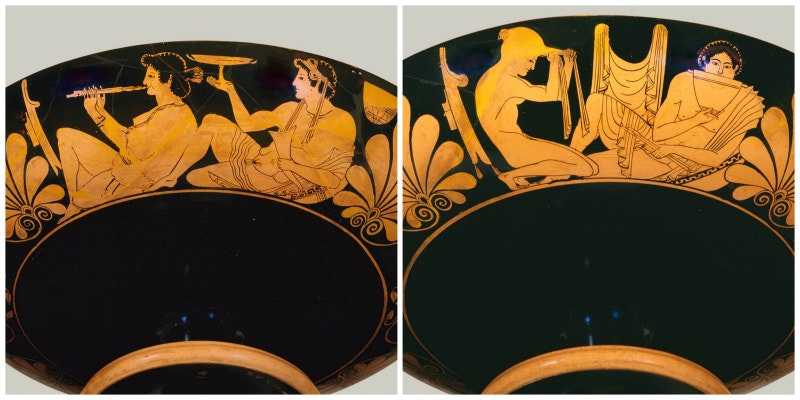

Paintings on drinking cups and wine-mixing vessels depict a lot of drinking, throwing up, and explicit sexual acts (so explicit, in fact, that many museums don’t put them on display). The fairly tame decoration on the drinking cup below carries a simple message: male symposium guests can expect music and other kinds of entertainment while they mingle with women who aren’t citizens’ wives or daughters. On one side of the cup, a guest listens to a woman play the flute. Because the painter shows her with one bare breast, she has other job duties in the night’s contract. (Other drinking cups and vessels portray similar scenes, and it’s not always clear that the flute girl is also a sex worker.) On the cup’s second side, the fully nude flute girl ties up her hair, while her male companion helpfully holds her flute.

A drinking cup from around 500 BCE shows scenes from a symposium. At left, a flute girl plays before a reclining man. At right, she binds her hair next to the man, with her robes hanging in the background. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat Gift and The Bothmer Purchase Fund, 1993

Other examples of “unrespectable” women on decorated pottery are much more ambiguous. These types of paintings show women in respectable settings, next to wool baskets and other household items, but the women are naked, which strongly suggests they’re sex workers. Consider this painting on an oil flask: a nude woman stands before a mirror, presumably in the women’s quarters of a respectable home, for the room contains a wool basket and a small chest.

An oil flask from about 450 BCE shows a nude woman standing before a mirror between her wool basket and a chest (both symbols of respectable women). Photo courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum

Scholars have found it difficult to interpret such pottery (see note 1). Did a female sex worker commission this painting of herself as a business card or advertisement? Was the artist differentiating a more cultured (and more expensive) courtesan from her humbler, cheaper sisters? Was the artist mocking the very idea of a sex worker who thought she could pass as a respectable woman? Or was this oil flask—a type of pottery used by women rather than men—some sort of private boudoir gift from a citizen husband to his respectable wife? There’s simply no way to know. While we can say definitively that Athenian society equated respectable women with the making of textiles, it’s harder to understand the joke when a wool basket appears in a less-respectable context.

Notes

- A great deal of sexy pottery has survived, and scholars largely ignored it until the 1970s, when historians became interested in feminist history, family history, and gender roles. As noted above, you may not see many such examples on display in museums. Maybe it’s because the paintings are so raunchy (my students used to call them “pornottery”), but maybe it’s also because the paintings don’t fit our cherished Western image of a rational, philosophical Athens.

Resources

- Blundell, Sue. Women in Ancient Greece. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- ———. Women in Classical Athens. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1998.

- duBois, Page. Slaves and Other Objects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Keuls, Eva C. The Reign of the Phallus. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

- Mertens, Joan R. How to Read Greek Vases. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

- Oakley, John H. The Greek Vase: Art of the Storyteller. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1995.

- “Women in Classical Greece,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wmna/hd_wmna.htm.

- “Scenes of Everyday Life in Ancient Greece,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/evdy/hd_evdy.htm.

Deb Garish is a former content manager for PieceWork magazine.

Originally published October 26, 2017; updated March 22, 2023.