In Part One of Sheena Pennell’s series on Eleonora di Toledo, the author discussed the inspiration behind her quest to re-create the original burial stockings of Eleonora di Toledo.

Part Two detailed her investigations that led to calculating the dimensions, gauge, and yarn that she would ultimately use to make her reproduction of the stockings as historically accurate as possible.

Here, Sheena delves into knitting guilds in the 1500s and reveals some of the duties of Eleonora’s lady-in-waiting.

Today, many knitters belong to guilds such as The Knitting Guild Association (TKGA), but in the 1500s, guilds were more like unions. While each one was a little different, they had the same general goals:

- provide training

- ensure pay equal to the level of training

- standardize quality

- care for widows/orphans if a member were injured or killed

Depending on the size of the guild and its importance in the local community, it might even be involved in local government. We don’t know a lot about knitting guilds in Italy/Florence, but by comparing them to similar organizations in other parts of Europe and to the wool and silk workers’ guilds in Florence, we can get a rough idea of what life was like for members.

Children often learned to spin and knit as young as three years old. Around age 10, a boy (women were excluded from most guild roles) would be apprenticed to a master knitter. He would probably do little knitting apart from stockinette tubes such as stocking legs. Toes, heels, and pattern stitches were considered too advanced. This would be his only knitting until the master was satisfied with his speed and tension. Other duties might include tasks such as winding yarn, untangling skeins, weaving in ends, and running errands.

After three years, the apprentice became a journeyman. As the name implies, he would travel far and wide, learning from masters in other cities and countries. To become a master, he would be tested. Again, we don’t know the specifics of what the Florentine guild required, but another European knitting guild asked for a carpet, embroidered gloves or stockings, shirt or waistcoat, and felted cap—all to be completed within 13 weeks. If the journeyman succeeded, he would be one of the agucchiatori (master knitters). Considering how long it’s taking me to knit these stockings, I’m pretty sure I’d never make it past journeyman!

The author’s stockings in progress

The author’s stockings in progress

Only guild members could do business in the city. Nonmembers risked arrest, fines, or worse. Journeymen and master knitters would be issued tokens to show guild membership, which served as a business license and résumé, assuring fellow knitters and potential clients of their skills.

While we know that the Medici supported guilds, we also know they often took talented artisans under their wing, even if they did not belong to a guild or didn’t qualify for guild membership because of religious or immigrant status (yes, many guilds specified members had to be Catholic or Protestant and native-born). These favorites were often paid much higher rates and were exempt from guild rules.

We know from palace inventories that Eleonora di Toledo had at least three pairs of stockings made by a lady in waiting. These could have been a gift from one friend to another, or they could have been part of her duties to her lady, as things such as mending, alternations, and fancywork or the making of soft accessories often fell to someone in the household rather than to professionals.

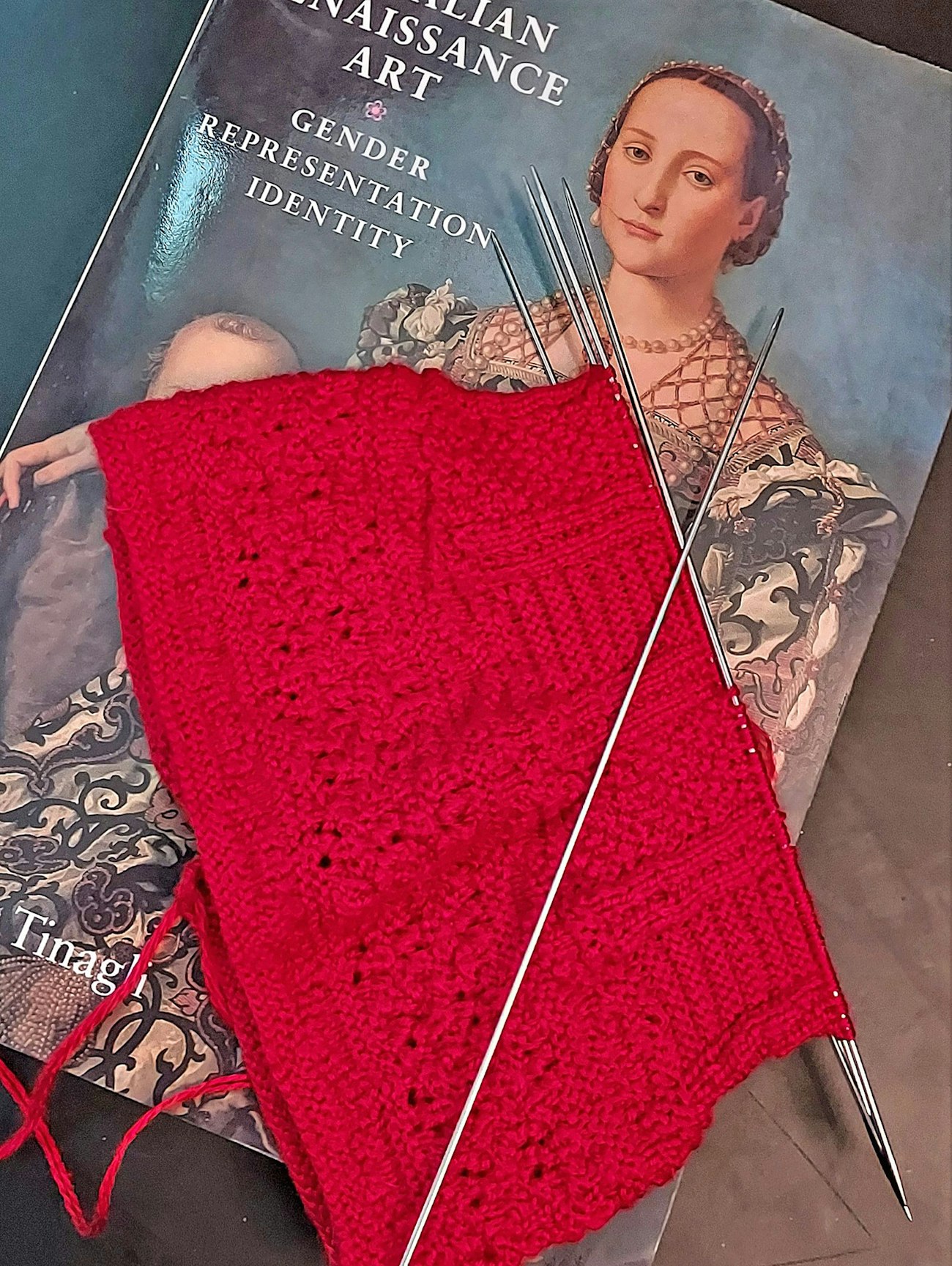

The author’s in-progress stockings, with one of her research books, Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity by Paola Tinagli, showing a portrait of Eleonora on the cover

The author’s in-progress stockings, with one of her research books, Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity by Paola Tinagli, showing a portrait of Eleonora on the cover

We don’t know who made Eleonora’s burial stockings, or what happened to the others in her wardrobe. All we know for sure is that Eleonora owned more than one pair of red, handknit stockings, and they were clear favorites in her wardrobe.

Sheena Pennell is the author, editor, knitwear designer, and amateur historian behind KnotMagick Studios. She has studied art conservation with an emphasis on textiles in Florence, Italy. The Eleonora project is based on a portion of her thesis, which focused on the challenges facing conservators working with burial garments.