This is the second installment of Jill’s story about her mother’s sewing and needlework collection. To start from the beginning, see “The Anatomy of a Collection: Lessons by Correspondence” in PieceWork Spring 2021. —Editor

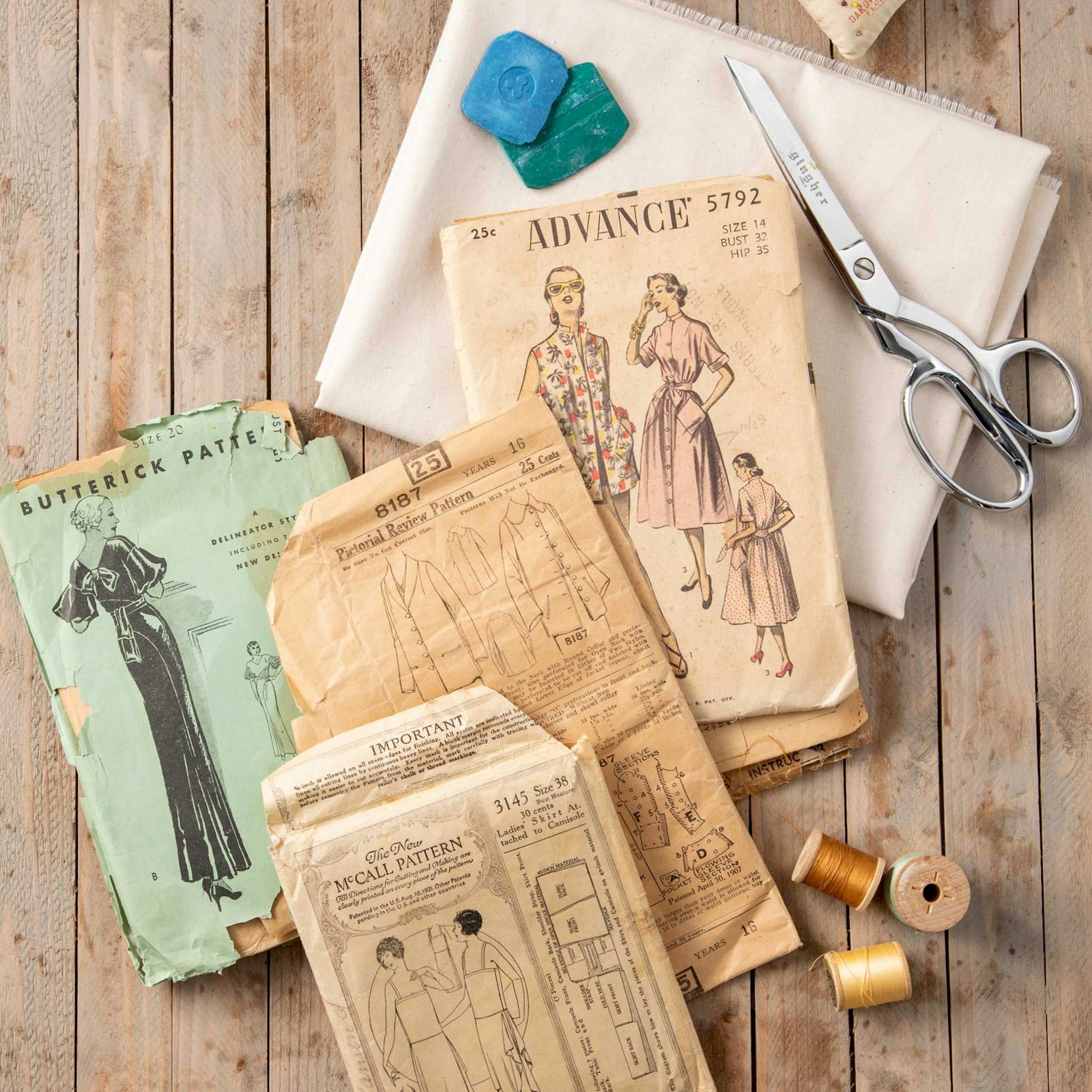

As I sat in my mother’s sewing room, sorting through her treasured fabrics, jars of buttons, and seemingly endless magazines and booklets, I was not sure where to go with the small stack of paper patterns before me. What I didn’t know in that moment is that my encounter with these aged, dusty, and (what appeared to be) lifeless remnants of tissue paper opened the door to a vast amount of concrete research material.

Old paper clothing patterns are not uncommon, and in fact, patterns and pattern-making companies have a rich, well-documented history. Today’s tissue patterns in an envelope—complete with guidelines and instructions—are not unlike patterns produced beginning in the 1860s. These patterns, made for the home sewer, eventually came with printing on the pieces, standardized sizes, grading, fabric recommendations, and detailed instructions. Some were products of large publishing companies, such as Vogue, while others came exclusively from retailers. Today, four manufacturers of sewing patterns for the home sewist from this period still remain: Butterick, McCall, Simplicity, and Vogue.

A Closer Look

This small stack of paper patterns included a Delineator-style dinner or formal afternoon gown for women and misses by Butterick Patterns. Although not dated, I could decipher that this was circa the 1930s simply by the silhouette of the gown. Next was a New McCall pattern dated August 16, 1921, containing a “Ladies’ skirt attached to camisole.” Both patterns were in excellent condition, neither having been used, and they remained precisely folded and perfectly nested in their respective envelopes.

The print on the pattern for the camisole was a beautiful denim blue color, and although tempted, I did not fully unfold every piece for fear they would not return to the envelope in a manageable form. (Such is the result of every pattern I have ever lovingly unfolded only to never return it to its pristine shape, snugly fitted into its envelope.)

I looked through the rest of the stack and began researching the three brands with which I was not familiar: Pictorial Review, Advance, and Anne Adams. I learned that the Pictorial Review pattern was the oldest of the three, dated April 30, 1907, and was for a misses’ jacket. I was happy to have found the date, since the garment illustration, simple and basic in design, exhibited no obvious distinguishable characteristics as to its period. The uniqueness of this pattern was that the complete instructions were on the outside of the envelope with no printing on the pattern pieces themselves. From what I could find, this was common for patterns during that time.

Like Vogue, Pictorial Review was originally a magazine. It was published to help promote clothing patterns developed by William Paul Ahnelt, German immigrant and owner of the American Fashion Company. This monthly women’s magazine was first published in September 1899 and at its height in 1931, entertained over 2.5 million subscribers.

A 1915 article in Pearson’s Magazine regarding the impact of Ahnelt’s influence stated, “When he landed here in 1888, fashion illustrations were not existent. Depressing woodcuts offered some idea to such as had prophetic insight as to what a gown might look like under the conditions not shown. He altered that. And if those magazines which deal wholly or in part with fashions feminine present now an attractive appearance, it is to William Paul Ahnelt that thanks are owed.”

One of the pattern envelopes contained a 1951 newspaper cut into an apron pattern.

I was surprised to find scant sources when researching Advance and Anne Adams. Regardless, the two patterns were clearly from the 1940s and 1950s, respectively, for a beach coat and a dress by Advance and an apron by Anne Adams. The former was an exclusive brand name for J. C. Penney beginning in 1933. Anne Adams, on the other hand, was a mail-order-only pattern company that advertised in newspapers throughout the United States. Owned by a larger publishing company called Reader Mail, Inc., out of New York City, it was also responsible for clothing patterns under the name of Marian Martin, needlework patterns by Alice Brooks, and quilting patterns by Laura Wheeler. With the limited information available to me, I could not find if, in fact, these were “real” women or just brand names. I believe they were the latter.

What intrigued me about the Anne Adams’s torn and well-used envelope was the pattern inside made from newspaper. Obviously not the original pattern, this newspaper appeared to be a copy of a pattern for the apron that the envelope once contained. I could conclude this from a few tissue pattern pieces and the instructions, which remained intact. This nugget continued to pique my interest as I pored over the contents of the partial newspaper articles that made up the apron pattern.

Smelling slightly musty and feeling a little dusty, this historical record, serving a double life as a pattern, was from a Detroit Free Press dated Saturday, January 20, 1951, and contained headlines that could pass for today: “England’s Flu Deaths Jump,” “Mass Slayer Jailed for Life,” and “Cold Clamps 52-Below Grip on Alaskans.” Its ads featured Kline’s and Himelhoch’s, two famous Detroit department stores. Of course, one could not miss the back side of the paper punctuated with, of course, an automotive ad by Buick. Little did the homemaker know that when she ever so carefully cut this pattern from her newspaper, she would someday delight a curious reader fascinated by the study of everyday life.

Pictorial Review, November 1930. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Lost to Time

Eventually, Pictorial Review magazine was sold and merged with a magazine called Delineator; however, it could not survive the Great Depression and met its demise in 1939. I could not find exactly how long Advance maintained its partnership with J. C. Penney, but in 1966, it was purchased by Puritan Fashions and dropped the name Advance. And finally, as far as I can tell, Anne Adams continued until around 1985.

Although they no longer exist as production companies, the patterns they printed still live on in the collections of those interested in these vintage designs. Today, a simple internet search can find all kinds of old patterns for purchase. From originals to reproductions, these old patterns are plentiful and quite affordable.

For me, these and so many other patterns bring back warm feelings of a simpler time. I remember as a young girl spending what felt like hours with my mom in our local drugstore’s sewing section. I fondly recall thumbing through page after page of pattern books in a dream-like state with a star in my eye. The prospect of me in one of those beautiful garments gave me such a thrill! I just knew my mother could—and often would—re-create a magical garment according to my own specifications, just how I imagined. Some kids loved toys; I loved clothing.

For now, I will lovingly act as caregiver for these old patterns and wonder if their previous owners imagined themselves in these garments as I do today.

The Anatomy of a Collection

For adult children whose parents now reside in nursing homes or assisted-living facilities, cleaning out one’s family home becomes a rite of passage. Beginning the process is often the most difficult first step.

My mother, Louise, left her home under unfortunate health circumstances in 2017. Her hasty exit, failing health, and the need for skilled care prompted my siblings and me to arrange for proper care immediately. A return to her home was no longer possible, and my sister and I knew it was time to begin the arduous process of cleaning out the family home. Since my mother was of the generation that threw nothing away, this task was not for the faint of heart.

The Anatomy of a Collection—a series of three short PieceWork articles—brings to light items discovered in my mother’s “stash of goodies,” as she called it. This collection of antique patterns, how-to sewing books, magazines, buttons, and notions piqued my interest as both my mother’s daughter and as a professor of fashion merchandising. Knowing they had to be more than just old castaways, I began to search for the life these objects once lived. Like an archaeologist on an expedition, I soon became intrigued by what I found. I thought you might, too.

Resources

- “Anne Adams Sewing Patterns.” The Vintage Traveler (blog), September 20, 2018. thevintagetraveler.wordpress.com/2018/09/20/anne-adams-sewing-patterns-fall-1938/

- Endres, Kathleen L., and Therese L. Lueck. Women’s Periodicals in the United States: Consumer Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 1995.

- “Laura Wheeler and Alice Brooks.” Quilt History Tidbits, quilthistorytidbits--oldnewlydiscovered.yolasite.com/laura-wheeler-and-alice-brooks.php

- Martyn, Wyndham. “The Man Who Was Converted.” Pearson’s Magazine 34, 5 (July 1915), 109–114.

- “More About Marion Martin, Anne Adams, Alice Brooks, and Their Sisters.” Witness2fashion (blog), January 5, 2015. witness2fashion.wordpress.com/tag/reader-mail-patterns/

Jill Ouellette is a professor of fashion merchandising in a small, private liberal arts college in southern Michigan, where she now resides. She brings to the classroom more than 20 years of teaching experience, work in the industry, and study abroad. Through teaching, she shares her knowledge and passion in the areas of historical fashion, textiles, corporate social responsibility, and environmentally sustainable business practices. She dedicates this series of articles to her late mother.