For Mom, nothing was more joy-filled than her time spent sewing. She was an incredible seamstress who could make magic out of the simplest materials. She was naturally skilled, was constantly developing her craft, and never stopped producing some of the most beautiful clothing and quilts I had ever seen. For that, she was a true hero of mine, and I will never forget, as a child, being lulled to sleep by the hum of her sewing machine in the next room.

My sister and I put off sorting her sewing room, but one sunny winter afternoon, the time finally came. We could no longer ignore the inevitable and started dissecting the room’s contents. Bobbin-lace pillows, cupboard after cupboard full of fabrics, shelves full of patterns and books, and containers overflowing with notions of all types for every conceivable sewing situation in which one might find oneself. This dizzying array of accoutrements was punctuated by some very old and distinguishing objects we separated from the more modern items.

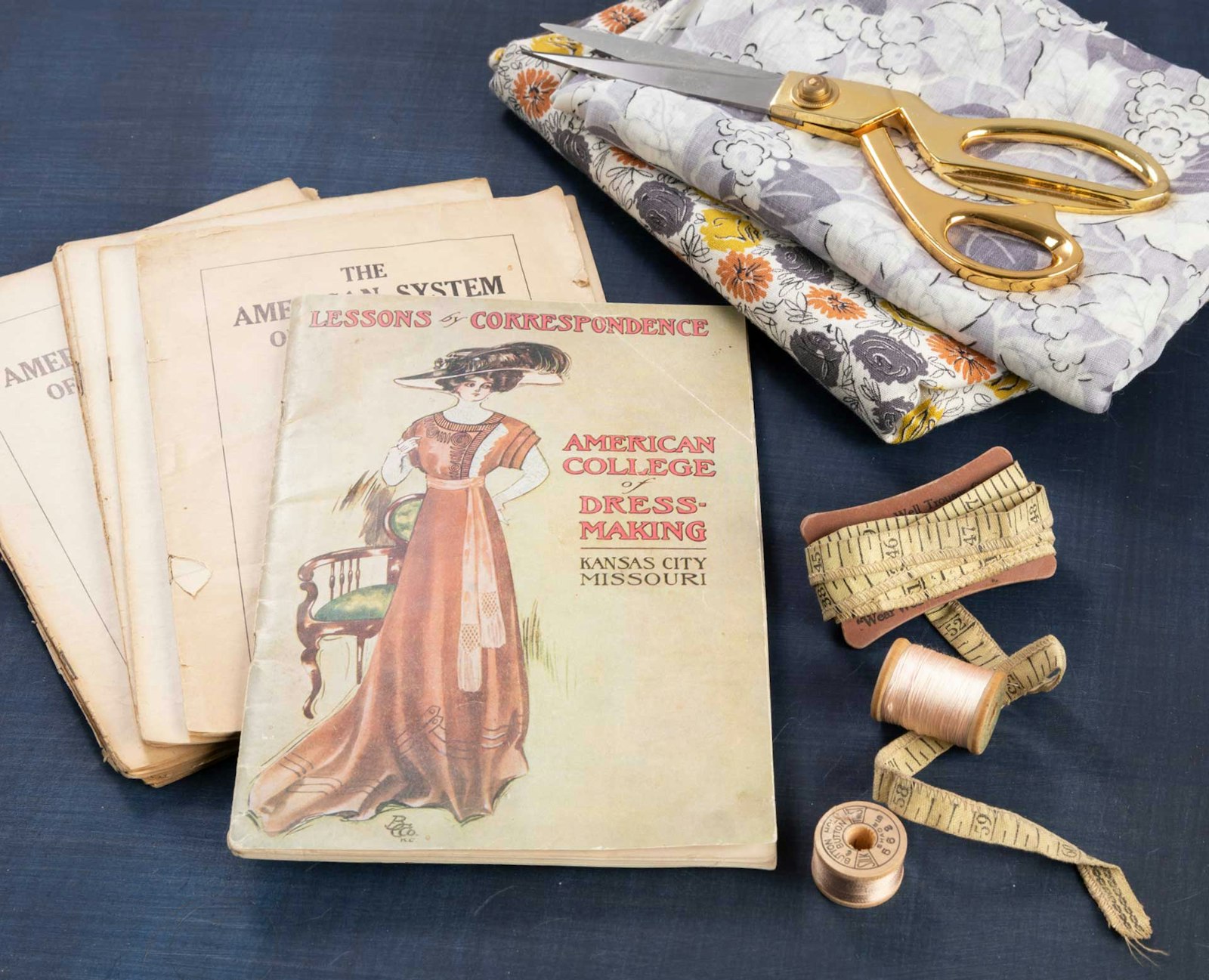

The first item I found was a set of small pamphlets entitled Lessons by Correspondence, published by the American College of Dressmaking, Kansas City, Missouri, copyright 1910. In relatively good shape, the set included 14 of 20 lessons, a pressboard tailor’s square in excellent condition, and a small booklet called Lessons by Mail. This informational booklet is simply a gem. If you were interested in learning how to become a dressmaker, this booklet contained all you would need to know including an application to the program, payment plans (either a full enrollment fee of $20 or installment plans of $5 then $2 for the next 10 months), testimonials of successful dressmakers, and a copy of the diploma you would receive upon completion of the course.

Full of persuasive content, this booklet offered the broadest appeal. The booklet states that there were “40,000 women learning to save on their dressmaking bills . . . ” because “we can teach a student wherever a letter can go.” The company argued that it could meet the needs of women across generations and social strata: “To all classes of women, we unhesitatingly offer our course of instruction. . . . Women of mature years pursue our correspondence instruction with the same zeal that they would a college course, minus the annoyance of going to school after they are grown.”

Further enticements included “women could dress better and earn $5,000 per year by putting their dressmaking skills to use, having learned from the largest institute of its kind in the world.” (By way of context, the maximum salary paid to Missouri teachers in 1910 was $200 per month.1)

The 20 lessons included in the course are full of instructions, schematics, and advice.

Diving Deeper

I was interested to discover more about the American College of Dressmaking, and I initially thought a simple Google search would surface results of even an introductory level. However, I was surprised and disappointed to find virtually no results, other than Miss Pearl Merwin, the author of the dressmaking instruction book that accompanied the lessons. I was unable to locate her biography, background of the developers of such a curriculum, or further information about the college.

What I could not find regarding the American College of Dressmaking was how it fit into the new exploration into sewing education that occurred around the turn of the century in America. Considerable research exists on this subject, ranging from the types of schools offering sewing education to the philosophical and practical reasoning behind teaching young ladies to sew.

Training schools and dressmaking apprenticeships existed throughout the United States and were especially important post–Civil War to World War I. Sewing could be a skilled hobby used for practical necessity, and it was considered to aid in molding and shaping young women of varying classes, ethnicities, and backgrounds in their roles in and out of the home. Sewing lessons could begin when a girl was young through home economics classes at schools or as lessons passed down from other women in the household. Some mothers relied upon schools and formal programs, such as the Lessons by Correspondence, to teach their daughters if they themselves worked in a factory and did not have the time to teach them.

Dressmaking also allowed women to start their own dressmaking businesses, contributing to family incomes. For some, dressmaking was a real alternative to the middle-class standard of domesticity, exposing these dressmakers to higher-class clientele. Well aware of that fact, the American College of Dressmaking persuaded the young and potential students with these words: “Wealthy women in the cities will go to the dressmaker who does the best work. For this reason, every woman should perfect her knowledge of dressmaking.”

As I researched this subject, I began to put the pieces of the puzzle together. The language that was used in the American College of Dressmaking pamphlet to recruit young ladies into this program was truly enticing. It spoke of elevating one’s sewing skills into more than just mere mending, and instead to a place of skilled and reputable business ownership. It promised benefits far beyond a simple domestic skill. The correspondence method, too, was substantial as it reached thousands of women “in almost every city, town, village, hamlet, and neighborhood in the United States and . . . in Canada, Mexico, Australia, South America, Africa, India, British West Indies, Japan, Cuba, France. . . .”

The pamphlet awakened the dream of young ladies everywhere to this exciting career as a dressmaker. I was also struck by this program’s authenticity and passion not only for dressmaking but for the dressmaker. I now wonder, who was this young lady who took these courses and whose lessons ended up in my mother’s collection of antiques? Did she earn a diploma? Was she able to branch out on her own as an entrepreneurial dressmaker? Did she help support her family? What creations did she sew? I will never know the answers to these questions. I just hope that her dreams came true.

The pamphlets included a section entitled “Letters of Endorsement” singing the praises of the American System of Dressmaking course.

The Anatomy of a Collection

For adult children whose parents now reside in nursing homes or assisted-living facilities, cleaning out one’s family home becomes a rite of passage. Beginning the process is often the most difficult first step. However, this test of courage must be met at some point in almost every child’s life. For me, it was a lesson I never expected.

My mother, Louise, left her home under unfortunate health circumstances in 2017. Her hasty exit, failing health, and requirement of skilled care prompted my siblings and me to make arrangements immediately. Knowing a return to her home was no longer possible, my sister and I knew it was time to begin the arduous process of cleaning out the family home. Since my mother was of the generation that threw nothing away, this task was not for the faint of heart.

The Anatomy of a Collection—a series of three short articles that will appear in PieceWork—brings to light items discovered in my mother’s “stash of goodies,” as she called it. This collection of antique patterns, how-to sewing books, magazines, buttons, and notions piqued my interest as both my mother’s daughter and as a professor of fashion merchandising. Knowing they had to be more than just old castaways, I began to search for the life these objects once lived. Like an archeologist on an expedition, I soon became intrigued by what I found. I thought you might, too.

Notes

1. Based on data sourced from the Official Manual of the State of Missouri and included in Prices and Wages by Decade. University of Missouri Library Guide, libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1910-1919.

Resources

- Cramer-Reichelderfer, Angela L. Fall of the American Dressmaker 1880–1920. Theses and Dissertations. Dayton, Ohio: Wright State University, 2019.

- Gordon, Sarah. Make It Yourself: Home Sewing, Gender, and Culture, 1890–1930. Columbia, Missouri: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Jill Ouellette is a professor of fashion merchandising in a small, private liberal arts college in southern Michigan, where she now resides. She brings to the classroom more than 20 years of teaching experience, work in the industry, and study abroad. Through teaching, she shares her knowledge and passion in the areas of historic fashion, textiles, corporate social responsibility, and environmentally sustainable business practices. She dedicates this series of articles to her late mother.

This article was published in the Spring 2021 issue of PieceWork.