The Victorian era (1837–1901) was in many ways an age of contradictions. Scientific and industrial progress were opening new horizons and opportunities yet society continued to adhere to strict rules of appropriate behavior for men and women. The Victorians dutifully followed those rules yet were deeply romantic and embraced sentimental symbolism as a means to express their feelings.

The increased introduction of exotic plants and an interest in the natural world led to an infatuation with horticulture, botany, and gardening. Flowers were a common subject in art, literature, and home decoration. Perhaps it is not surprising that floriography—assigning meaning to flowers—saw a resurgence at the beginning of the nineteenth century and remained popular through World War I (1914–1918).

Whimsical floral illustrations with their “meanings” decorate these Victorian trade cards by Bognard, Paris. 1840–1890. Collection of the author.

Floriography has been known since the early ages. Greeks and Romans decorated their poets, patriots, and victors with floral wreaths, laurels, and oak crowns. At the end of the Roman Empire, the practice fell into disuse but returned during the Middle Ages—a knight showed his devotion to a lady by wearing her color on his casque, and she responded to his attention by choosing special flowers to wear on her dress.

The custom of putting together a bouquet of small flowers to communicate a secret meaning is thought to have originated in Turkey, where such a missive was called a salaam (salutation). This “mysterious language of love and gallantry” was introduced to Europeans with the posthumous publication of Turkish Embassy Letters by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762). She wrote: “There is no colour, no flower, no weed, no fruit, herb, pebble, or feather that has not a verse belonging to it: and you may quarrel, reproach, or send letters of passion, friendship, or civility, or even of news, without ever inking your fingers.”

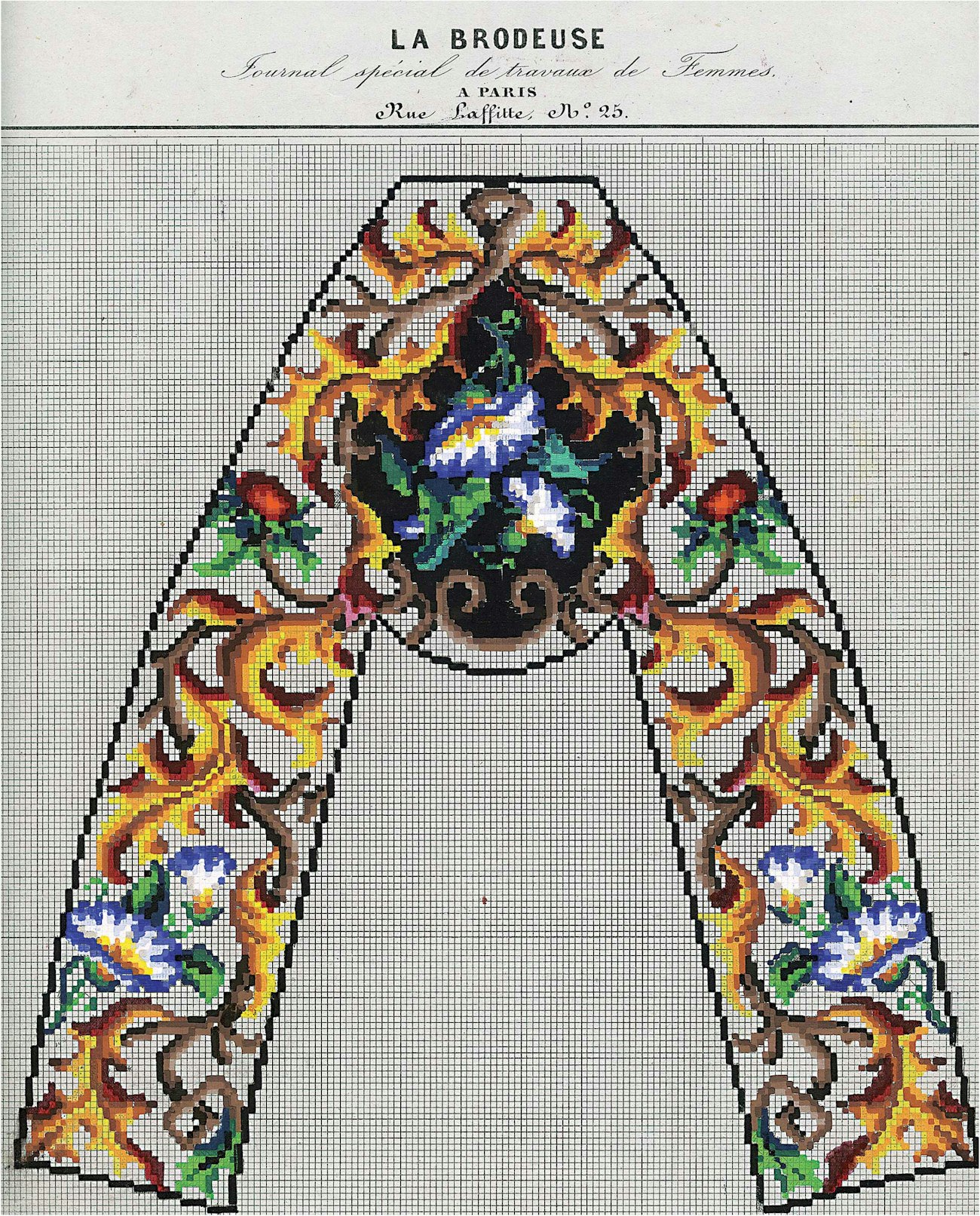

Using this slipper pattern featuring acanthus, rosebuds, and convolvulus from La Brodeuse, a Victorian woman could send a secret message to her husband or a male friend. Collection of the author.

Although Lady Mary didn’t call it “the language of flowers,” Westerners adopted the term perhaps as a result of the publication in France in 1819 of the first formal dictionary on the subject, Le Langage des Fleurs by Charlotte de La Tour (thought by some to have been the pen name of Louise Cortambert, dates unknown). One of the most popular English versions of this dictionary, still in print, is the Routledge and Sons 1884 London edition with dainty drawings by the children’s illustrator Kate Greenaway (1846–1901).

Illustrated floral dictionaries, descriptive lithographs, and entire books devoted to this subject appeared across Europe and in the United States. For many Victorians, “no spoken word could approach the delicacy of sentiment” of a flower. The books were similar in content and structure: an alphabetical list of flowers with their symbolic meanings derived from classical mythology or folklore, poetic examples and quotes, and the Floral Oracle, a fortune-telling game involving flowers.

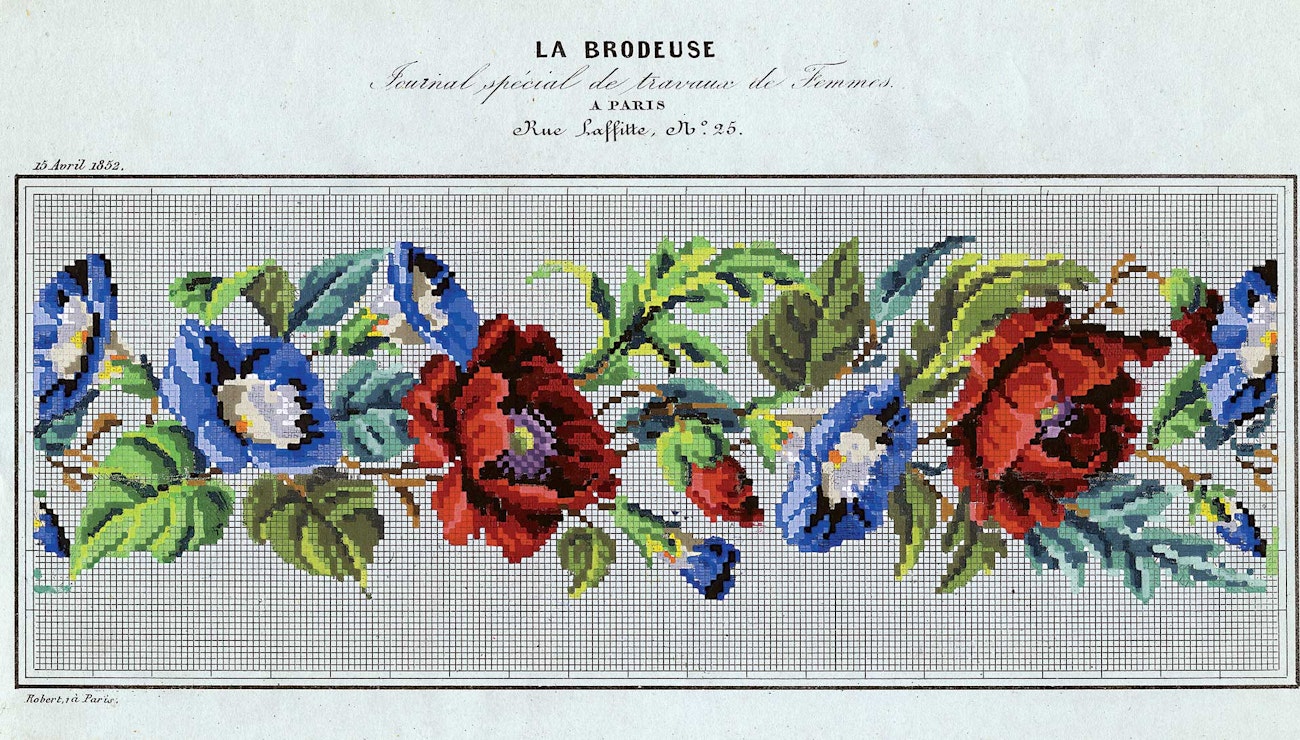

The combination of red poppies and blue convolvulus suggests that “night will bring consolation.”

Flowers, Their Language, Poetry and Sentiment, (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1870), advised: “The richly varied and magnificent flora of our American continent offers a floral vocabulary capable of almost unlimited application. . . . The numerous brilliant and original tokens already set forth in explanation of the American language of flowers prove we are not dependent upon European codes for emblematic communion.”

Although floriography was considered “a gentle art,” requiring little study, a great deal of skill and ingenuity were needed to form or explain in a sentence the meaning hidden in a flower arrangement. A small nosegay of plum blossoms, sweet pea, convolvulus, and forget-me-nots sent a lover’s message: “Don’t forget to keep your promise to meet me tonight.” A lacy bunch of ivy, snowdrops, and myrtle or rose implied, “Your friendliness bids me hope to obtain your love”; the combination of rose, ivy, and myrtle simply conveyed “beauty, friendship, and love.” Sometimes the symbolism of a flower had to be modified to reflect cultural and geographical differences. For example, while in the Muslim world fragrant almond blossoms were a symbol of hope because they bloomed on the bare branches, Victorians viewed them as a symbol of thoughtlessness and indiscretion as in England the early blooms often were damaged by frost.

The language of flowers was part of everyday correspondence, dress, arts, literature, poetry, greeting cards, scrap albums, and needlework. As language-of-flowers publications proliferated, so did embroidery designs with lavish floral bouquets, wreaths, and vases. We can picture Victorian women selecting their embroidery designs with flower symbolism in mind.

I’ve deciphered some of the possible messages in several of the Victorian needlework patterns from the nineteenth century in my collection. A pattern for slippers (probably men’s) from the French magazine La Brodeuse includes scrolls of acanthus “patron of the arts”; small red rosebuds “purity”; and blue convolvulus “night” and “repose.” Another pattern, perhaps for a bell pull, this one from the April 15, 1852, issue, might have been appropriate for a time of mourning: “May the night’s sleep bring you consolation” (red poppy, “consolation”; blue convolvulus, “nighttime”).

A bell-pull pattern from the Parisian Le Magasin Des Demoiselles might be telling a story of love with its yellow tulip (“hopeless love” or a declaration of love), nasturtium (“patriotism”—perhaps the object of affection was a military officer), large white peonies (“I am bashful”), white apple blossoms (“I prefer him; fame speaks him great and good”), sprig of red currants (“He pleases all”) and small blue flax flowers (“I feel your kindness”).

A yellow tulip symbolizing hopeless love is at the center of this Victorian bell pull. Collection of the author.

The Arum Tea Cosy from the September 1869 issue of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine speaks to traditional Victorian values. The calla lily is a sign of modesty, but also of “magnificent beauty.” Single roses underscore simplicity and beauty. Red rosebuds are “pure and lovely” whereas the stylized ivy scrolls describe a happy marriage.

Following World War I (1914–1918), the language of flowers no longer had a place in a changing world. It was relegated to the realm of sweet remembrance of a time when one could “. . . speak / Of life and joy, to those who seek / For love divine and sunny hours, / In the language of the flowers.” —The Language of Flowers (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1875)

Further Reading

Connolly, Shane. The Secret Language of Flowers: RediscoveringTraditional Meanings. New York: Rizzoli, 2004. Out of print.

Greenaway, Kate. The Language of Flowers. 1884. Reprint. Miami, Florida: Hard Press, 2012.

Kirkby, Mandy. A Victorian Flower Dictionary: The Language ofFlowers Companion. New York: Ballantine Books, 2011.

Laufer, Geraldine Adamich. Tussie-Mussies: The Language of Flowers. New York: Workman, 2000. Out of print.

Loewer, Peter Thomas. Loves Me, Loves Me Not: The HiddenLanguage of Flowers. Brentwood, Tennessee: Cool Springs Press, 2007. Out of print.

Irina Stepanova is a designer, collector, and owner of Mishutka Design Studio, mishutkadesign.com. She writes about Victoriana, and her projects and embroidery designs are a tribute to nineteenth-century women’s needlework.

This article was published in the March/April 2013 issue of PieceWork.