The history of the running stitch is really the history of the needle and thread. One can assume an eyed needle (not an awl) led to sewing, which meant the creation of the running stitch, used on clothing, shoes, hats, and other needed items such as storage bags, bedding, and shelter (and probably the whip stitch for sewing animal skins together).

The world’s earliest needle was discovered in a Siberian Denisova cave. The Denisovans were an archaic species of humans before Homo sapiens. This needle is under 3 inches (8 cm) in length, has an eye, is made of bird bone, and is thought to date back some 50,000 years. A point from another possible needle was found in a cave in South Africa and is dated around 61,000 years ago. The oldest known sewing thread is flax; it’s about 34,000 years old, was discovered in a cave in the country of Georgia, and was probably the result of naturally occurring rotted flax stems. Other types of thread like animal and human hair and other plant fibers, such as the midribs of various species of leaves and strong narrow vines, were also used.

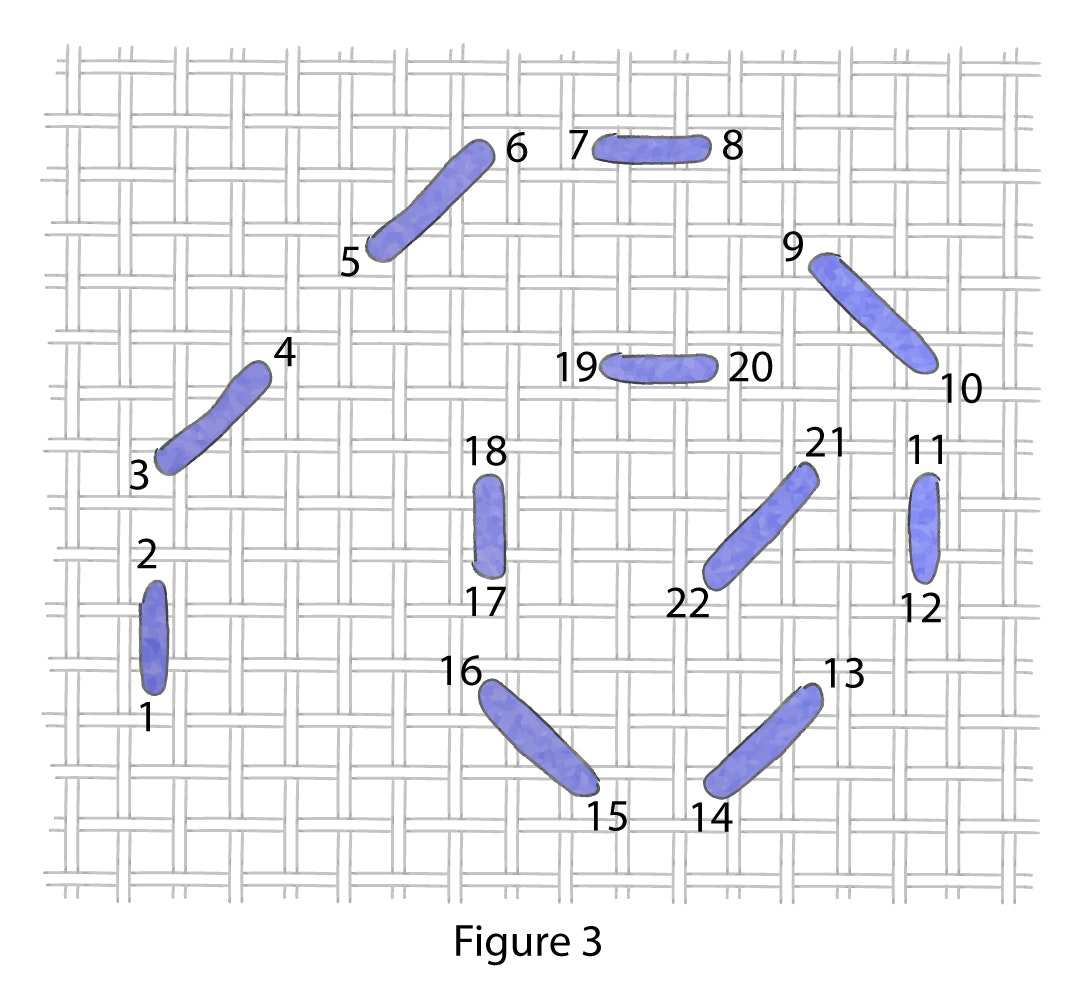

Created independently around the world, the running stitch (Figures 1, 2, and 3) is the simplest and easiest of all stitches and is a member of the line stitch family. It’s accomplished by “running” a threaded needle in and out of fabric, either in a sewing motion or as individual stab stitches. The individual stitches can be of equal or unequal lengths, equal or unequal spacing, and used on all plain and evenweave fabrics of various fiber content, including leather. It’s also used as a basic foundation stitch for many composite embroidery stitches. A longish, thin needle, either sharp or blunt, is usually preferred when multiple stitches are gathered onto the needle, but a shorter needle is easier to use for embroidery purposes, especially when working the double running stitch (Figure 4).

The quick, easy, and reversible running stitch, also known as basting or sewing stitch, can be worked horizontally (left to right or right to left, Figure 1), vertically (up or down), diagonally (Figure 2), or around curves (Figure 3). It can be stitched in rows (parallel columns or staggered), outlines, bands, borders, fillings, or as groupings (see stitched example). The length of the running stitch depends upon the weave of the ground fabric, size of the thread, and the whim of the stitcher. This very versatile stitch is used in various embroideries and samplers of all ages and from numerous nations, sewing construction (tacks, tucks, gathering fabrics, as well sewing fabrics together), pattern darning (mending or embellishing), starting and ending threads in delicate embroideries to avoid knots, quilting, patchwork, crazy quilting embroidery, and smocking.

The running stitch is the basis of pattern darning embroideries throughout the ages and around the world. Pattern darning was not only used to repair fabrics but also for embellishing fabrics. Some examples of pattern darning embroideries include the Peruvian Nasca sampler from the 2nd century BCE; 13–16th century Egyptian Mamluk samplers; pattern-darning samplers from northern Europe, including Belgium, Britain, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands; Indian kantha and rafoogari for the mending of shawls, saris, and sashes; and Japanese sashiko, kogin, and boro mending stitcheries. The European samplers were generally used as teaching tools to show schoolgirls how to mend valuable worn fabrics (garments and household items, such as bed curtains and table linens) and learn the alphabet and how to read.

The reverse side of Deanna’s sampler is just as lovely as the front.

The reverse side of Deanna’s sampler is just as lovely as the front.

Almost any type of thread can be used as long as it’s compatible with the ground fabric weave. Some possibilities are stranded floss, cotton, silk, or polyester; various cotton, silk, and linen threads; pearl cottons; knitting, crochet, or crewel yarns; metallic threads; silk or polyester ribbons; sashiko thread; cording; and even narrow strips of leather. For long stitching runs in pattern darning and double running work, use an extra long length of thread. For pattern work use an away-waste knot to start and then to end the starting and ending threads, use a sharps needle to pierce several stitches on the back of the fabric. When using multiple threads, keep the threads as parallel as possible by using the railroading technique. This helps to retain the threads’ width and shine throughout the project. Except for gathering fabric, do not pull the thread taut. Let it lay gently on the fabric’s surface.

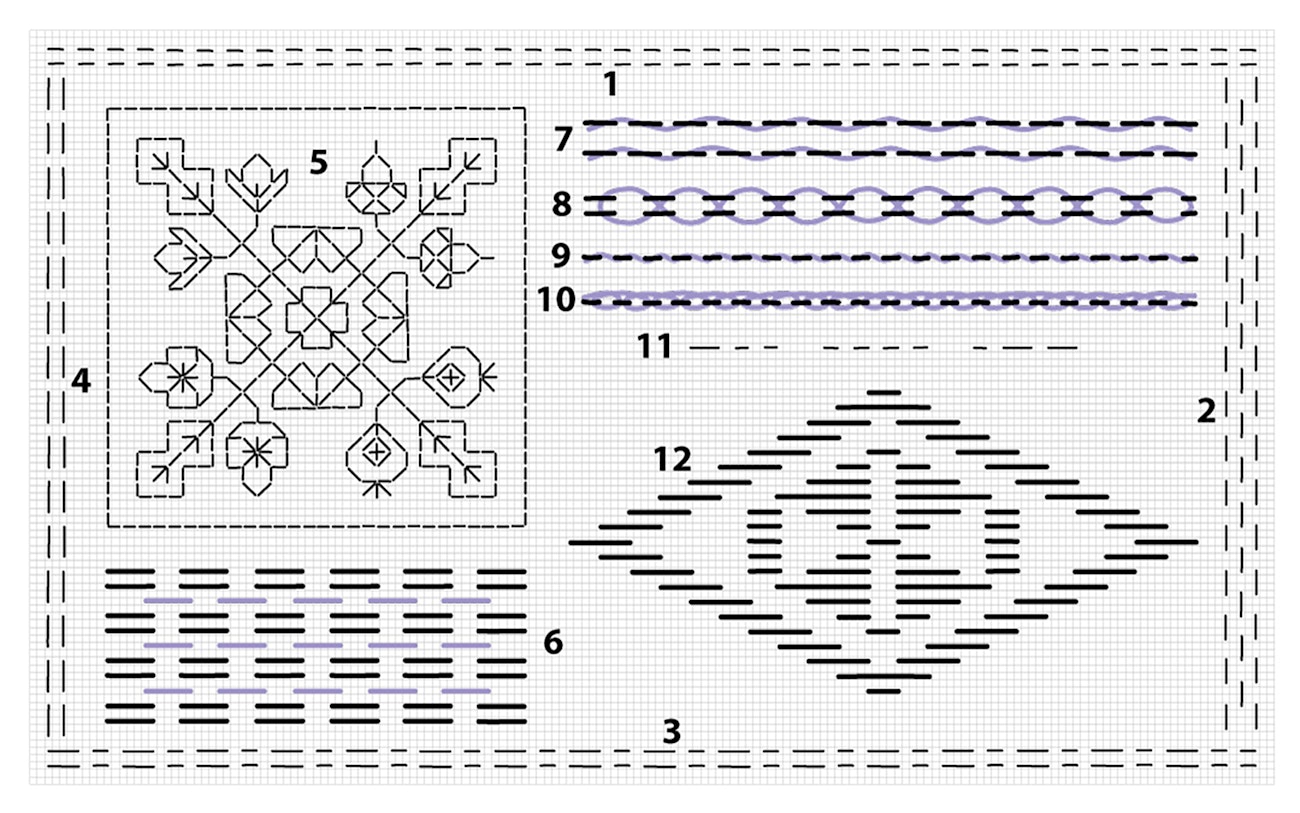

Some of the many running stitch variations include double or Holbein (Figure 4), threaded or laced (Figure 5), double threaded (Figure 6), whipped or cordonnet (Figure 7), looped (Figure 8), and pattern darning (Figure 9) to name a few.

The Running stitch with its numerous variations and its many different applications is exciting and mind-boggling.

Running Stitch Sampler Legend:

1. Running stitch border: use 2 strands of #310 over 2 and under 2 threads.

2. Staggered running stitch border: use 2 strands of #310 over 3 and under 3 threads.

3. Running stitch border: use 2 strands of #310 over 4, under 2, and over 2 threads.

4. Running stitch border: use 2 strands of #310 over 4 and under 2 threads.

5. Double running stitch design and border: use 1 strand of #310 over and under 2 threads.

6. Pattern darning design: use 3 strands each of #310 and #3746 over 6 and under 4 threads.

7. Threaded running stitch: use 2 strands each of #310 and #3746; #310 over 4 and under 2 threads except for the compensating stitches at end of row.

8. Double threaded running stitch: use 2 strands each of #310 and #3746; #310 over and under 4 threads.

9. Whipped running stitch: use 2 strands each of #310 and #3746; #310 over and under 2 threads.

10. Looped running stitch: use 2 strands each of #310 and #3746; #310 over and under 2 threads.

11. Running stitch initials in Morse Code (shown DHW): use 2 strands of #310.

12. Kogin design, use 4 strands of #310.

Deanna Hall West is PieceWork’s needlework technical editor; she previously was the editor of The Needleworker magazine.

Originally published April 23, 2019; updated September 7, 2022.