In this three-part series, the author examines the concepts in a sewing exhibition at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC. You can catch up by reading Part 1 on how and where girls learned their sewing skills, continue to Part 2 on sewing duties and technology, and finish with Part 3 below.

Textiles—like all objects from the past—contain meanings, as well as clues to the lives of the people who made them. A museum curator’s job is to study surviving objects and parse out their significance to their makers and owners. In an upcoming exhibition at the DAR Museum, we will be looking at items American women sewed (or, in some cases, knitted) in the 1700s and 1800s, to consider the many meanings embedded in their threads.

A large pictorial embroidery, expensively framed, for example, proclaimed the skill of its maker, the ability of her parents to send her to school (where she could spend time on ornamental sewing) and do without her help at home, and their pride in her accomplishments. Perhaps the subject matter of the Queen of Sheba holding her own against the famously wise King Solomon was a subtle statement celebrating women’s education, which was gradually becoming more widespread—and the curriculum, more academic—at this time.

Silk-on-silk embroidery with spangles by Elizabeth Meyers of Philadelphia, 1818, with painted background and figures by Godfrey Folwell. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 961,2020.13, gift of Kathryn Reeves-Hoche

Silk-on-silk embroidery with spangles by Elizabeth Meyers of Philadelphia, 1818, with painted background and figures by Godfrey Folwell. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 961,2020.13, gift of Kathryn Reeves-Hoche

In the exhibition, we also include some modern pieces, to show how women are still using their needles to express their emotions, aspects of their identity, and their opinions or concerns for improving their communities and the world. Not all of the illustrations here will be included in the exhibit, but they are examples of themes explored within.

Some meanings are clear and intended by their maker, like gifts of love or friendship. In the eighteenth century, many women stitched needlebooks for friends and family; for a male relation, a pocketbook (we’d call it a wallet) in crewelwork, Queen stitch, or Irish stitch (what we now call bargello) was a popular choice. These colorful items often have a man’s name and a date embroidered at the top, hidden by the flap, as Richard Alsop’s does, so we know that men were using them.

Pocketbook, gift of Mary Wright Alsop of Connecticut to her husband Richard, 1773. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 961, gift of Julia Rogers

Pocketbook, gift of Mary Wright Alsop of Connecticut to her husband Richard, 1773. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 961, gift of Julia Rogers

Textiles can also express identity, whether personal, regional, religious, or national. In the days before ready-to-wear clothing dominated our wardrobes, women essentially designed their own clothes in consultation with their dressmakers. Responding to fashion plates and what she saw her neighbors wearing, a woman would decide on a fabric and color, then pick and choose elements of current trends to suit her personal taste and comfort level. The early-1820s wearer of the gauze dress below probably liked the fashion for the bold, padded satin trim at the sleeves and hem, but she was not yet ready to lower the waistline as fashion plates were suggesting.

Silk-gauze and silk-satin dress with cotton wadding, 1821–23. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 2017.16, gift of Louisa Eifrig Rauth

Silk-gauze and silk-satin dress with cotton wadding, 1821–23. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 2017.16, gift of Louisa Eifrig Rauth

Regional styles, which developed in samplers and quilts, were quite possibly unconscious expressions on the part of their makers. But with the distance of time and through study by collectors and scholars, we can recognize the origin of a piece and learn about its maker, as well as about aesthetics and the spread of styles in her area. The Sykes family put together an album quilt whose colors, patterns, and arrangement of on-point blocks with sashing all communicate their southern New Jersey Quaker background.

Left: Sykes family album quilt, 1847, Burlington County, New Jersey. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 94.23, gift of Dorothy Truitt. Right: “Comb of Kaiulani,” quilt by unknown maker, Hawaii, 1920s. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, 2023.6

Left: Sykes family album quilt, 1847, Burlington County, New Jersey. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 94.23, gift of Dorothy Truitt. Right: “Comb of Kaiulani,” quilt by unknown maker, Hawaii, 1920s. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, 2023.6

Other textiles very consciously express regional allegiance. Hawaiians developed a distinctive style of quilt that combined American appliqué quilting and their own approach to design. Stylized motifs represent local flora and are influenced by traditional kapas, the beaten bark cloth made by indigenous Hawaiians before the arrival of American missionaries. The design of the one shown here is known as “The Comb of Kaiulani,” honoring Hawaii’s last princess, who died in 1899, a year after the United States annexed Hawaii—against the will of its people. The pattern title most likely intended to convey nostalgia for the years of Hawaiian rule—but it was also a popular pattern, so we cannot be sure what was in the mind of the quilt’s maker.

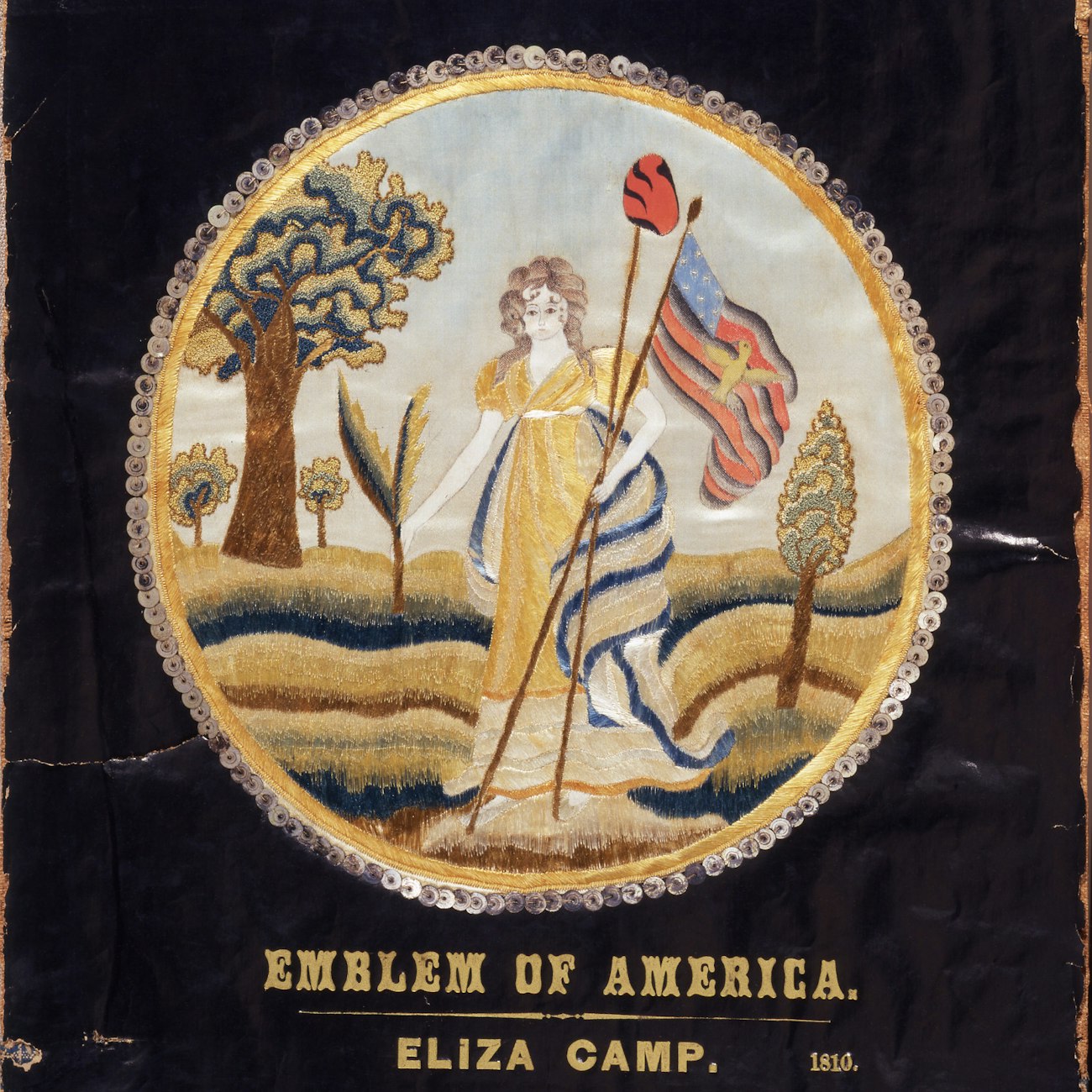

National identity and patriotism have also been expressed in textiles and dress. After the American Revolution, allegorical figures of America or Liberty were popular, with eagles and flags of secondary importance. Eliza Camp’s “Emblem of America,” copying a print by that title, features the red Roman Liberty cap draped on a “Liberty Pole” and skips the eagle entirely; it is typical of Federal-era iconography.

Silk embroidery on silk needlework with watercolor and spangles by Eliza Camp, 1810. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 82.44, gift of Marguerite Durkee

Silk embroidery on silk needlework with watercolor and spangles by Eliza Camp, 1810. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 82.44, gift of Marguerite Durkee

Subtler patriotic sentiments can also be found: Thousands of “Colonial” costumes were made for bicentennial events in 1976, most made from patterns published by Butterick and McCall’s. One made from a Butterick pattern, not in American-flag colors but in pastels approximating what a Colonial woman would have worn, will be included in the exhibition.

Cotton dress, 1976, made and lent by Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz. Photograph by Mark Gulezian. Courtesy of Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz

Cotton dress, 1976, made and lent by Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz. Photograph by Mark Gulezian. Courtesy of Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz

Before American women had the vote or were “allowed” by social convention to speak out publicly about politics or social issues, they used their needles to express their opinions and to support causes they cared about. Sewing for charity was a time-honored tradition, and “sewing societies” were founded in communities large and small. Some were focused on abolition; other groups sewed for their church or for the poor. During the Civil War, sewing societies on both sides sprang into action, sewing clothing and bedding for the troops and, later, things to sell at “Sanitary Fairs,” organized to support troop hospitals.

This doll was won at a charity fair in about 1860 in Massachusetts. Dolls for sale for raffle, often with full wardrobes, were popular offerings at such fairs. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 4119, gift of Alice Staples Lane

This doll was won at a charity fair in about 1860 in Massachusetts. Dolls for sale for raffle, often with full wardrobes, were popular offerings at such fairs. The Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 4119, gift of Alice Staples Lane

First-wave feminists at the turn of the twentieth century largely rejected the needle as a means to support their causes, preferring more direct action. Of course, women have continued by the millions to enjoy quilting, embroidery, and other needle skills in ways similar to their eighteenth- and nineteenth-century predecessors. But a new generation has rediscovered and reclaimed the “feminine” needle to express themselves politically, and today’s “craftivism” is represented in the exhibition, with quilts addressing racial justice, interfaith understanding, climate change, and other topics of note.

“Pussy hat” worn at the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, DC, and mittens, worn at Black Lives Matter and other marches in Minnesota. Hat made by Stephanie Szurek, worn and lent by Sarah Krispel. Mittens made and lent by Jennifer O’Brien

“Pussy hat” worn at the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, DC, and mittens, worn at Black Lives Matter and other marches in Minnesota. Hat made by Stephanie Szurek, worn and lent by Sarah Krispel. Mittens made and lent by Jennifer O’Brien

This exhibit is somewhat unusual in that it combines clothing, quilts, samplers and other needlework, even household linens, to discuss the huge role sewing played in women’s lives in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is unusual for the DAR Museum to include contemporary pieces, as our collecting and interpreting focus is usually pre-1900. We are excited to bring together nearly 150 objects from 1750 to 2023 (with even more in our adjacent study gallery and period rooms), inviting our visitors to consider all these needle skills together in the context of American women’s lives.

Sewn in America: Making, Meaning, Memory will be on view at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC, from March 15 through December 28, 2024.

Alden O’Brien has a BA in art history from Barnard College and an MA in Museum Studies in Costume and Textiles from the Fashion Institute of Technology. She has been curator of costume at the DAR since 1990, and over time she has been given charge of the dolls and toys, quilts, and most recently the samplers and needlework. She has curated nearly a dozen exhibitions; the next one, combining clothing, quilts, needlework, and household linens, will open in March 2024.