In this three-part series, the author examines the concepts in a sewing exhibition at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC. You can catch up by reading Part 1 on how and where girls learned their sewing skills, then continue to Part 2 below, and finish with Part 3 on the meanings conveyed through what we sew.

Those of us who enjoy looking at (and collecting, or replicating) the needlework of earlier eras—quilts, samplers, the many embroidery techniques, the countless charming crafty items—may not realize, and seldom consider, that these decorative works were done in addition to the more mundane household sewing tasks that almost every American woman performed. (Of course, this was also true outside the United States, but this exhibition focuses solely on America.)

Until the second half of the 1800s, household textiles—bed linens, tablecloths, and so on—had to be sewn at home. Very little ready-made clothing was available, so the women of the house had to sew all the children’s clothing, all their own undergarments (in the early 1800s, this could include corsets, which at the time were fairly simple and unboned), and men’s shirts and undergarments.

Some, but certainly not all, of the garments women would sew and knit at home are shown here, from L to R: nightcap (1840s), petticoat (1825–45), pocket (1750–1790), shift (1795–1815), stockings (1820s), apron (1914), drawers (1840s). Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Some, but certainly not all, of the garments women would sew and knit at home are shown here, from L to R: nightcap (1840s), petticoat (1825–45), pocket (1750–1790), shift (1795–1815), stockings (1820s), apron (1914), drawers (1840s). Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Women also often sewed men’s trousers and waistcoats at home, after tailors first fit and cut them. (Coats required more specialized tailoring skills.) Many women also did much of the sewing of their dresses even if they hired a dressmaker for help with fitting and cutting the bodice pattern, as many experts advised. Catherine Beecher, author of the best-selling housekeeping manual A Treatise on Domestic Economy, advised getting a dress “fitted (not sewed) at the best mantua-makers. . . and cut out a pattern” after which “a lady of common ingenuity can cut and fit a dress.” Women’s diaries detailing their sewing show that this advice was often heeded.

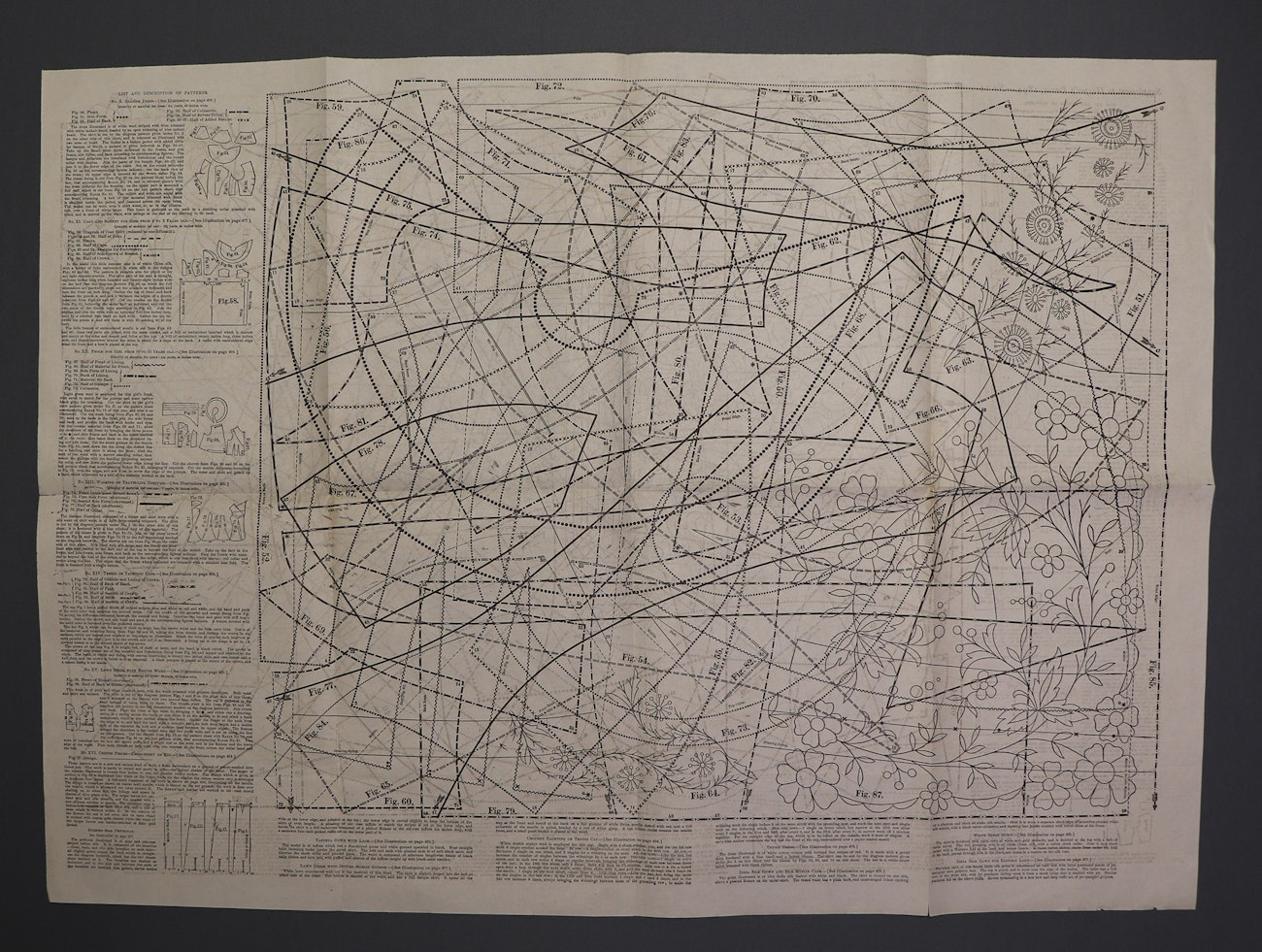

American garment patterns began appearing in the 1850s with small-scale drawings in magazines. During this decade, a few periodicals offered full-size overlapping patterns, which required tracing coded lines off an easily torn paper insert. And of course, both of these systems offered only one “average,” ideal size—fitting the pattern to your individual body was up to you.

Harper’s Bazar, 1896. Larger pattern pieces would have to be cut in two different pieces. Sleeve patterns were reused in several bodices and jackets. Garments were illustrated in the magazine pages, and the pattern outlines illustrated with a few basic instructions at the left. Collection of the author

Harper’s Bazar, 1896. Larger pattern pieces would have to be cut in two different pieces. Sleeve patterns were reused in several bodices and jackets. Garments were illustrated in the magazine pages, and the pattern outlines illustrated with a few basic instructions at the left. Collection of the author

A good fit was important, not only for the satisfaction of a well-made, good-looking garment but because women were constantly being told that “dress is an index of character.” For most of the nineteenth century, dresses were meant to fit snugly to the corseted figure. Without decent cutting and fitting skills, you might easily end up with a bodice straining at the seams or with badly matched patterns. It’s tempting to wonder whether the casual loosely gathered bodices of the 1850s were popular in part because they didn’t require an exact fit.

The introduction of precut, full-size tissue-paper patterns available in multiple sizes was a big advance, even if they still required some adjustments to make them fit the individual customer. Holes and notches showed grainline, where pieces should be matched, placement of trim and tucks, and so on. Initially, only extremely rudimentary guidance was given on the envelope or a separate paper. It was not until the 1920s that notations were printed on the pieces, although various companies did make improvements on the instructions offered.

Pictorial Review pattern for “Misses’ Costume” (a day dress),1913. Bodice piece, envelope with drawing of the dress design, and insert with layout and code for the notches and holes on the pieces. Collection of Drs. K. and B. Bohleke

Pictorial Review pattern for “Misses’ Costume” (a day dress),1913. Bodice piece, envelope with drawing of the dress design, and insert with layout and code for the notches and holes on the pieces. Collection of Drs. K. and B. Bohleke

Dozens of pattern-drafting systems, allowing the amateur or professional dressmaker to customize a pattern to her measurements, were marketed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. These were not terribly difficult to master but may have been used more often by dressmakers than by home seamstresses. Nevertheless, Catherine Huff made her burgundy taffeta wedding dress from one of these systems.

Dress, 1899–1900, made by Catherine Huff, Buchanan, Michigan, from the Hollenbeck & Stodderd pattern system, 1884, Lafayette, Indiana. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 98.69.1-2. gift of Marta K. Dodd. Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Dress, 1899–1900, made by Catherine Huff, Buchanan, Michigan, from the Hollenbeck & Stodderd pattern system, 1884, Lafayette, Indiana. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum 98.69.1-2. gift of Marta K. Dodd. Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Dressmakers—from the local woman who did some sewing for her neighbors to the more elite fashionable “modistes” from the big cities—were patronized by a fairly wide swath of society, not only the social elite. But drafting systems, paper patterns, and sewing instruction manuals all helped make fashionable styles more readily available to American women who may not have been able to access a professional because of geographical distance or economic circumstance.

Because nineteenth-century women lived in wildly different circumstances—in urban, rural or frontier communities, with strict upper, middle, working, and immigrant class distinctions—it is impossible for us to generalize about what percentage of their wardrobes these women sewed throughout the decades. Wealthier women were more likely to use dressmakers and even to delegate some of the “plain sewing” of sheets and basic garments to seamstresses hired for a week or more a few times a year, but no woman was fully exempt from sewing duties. The exhibition also looks at women who sewed for others: both professional dressmakers and seamstresses and enslaved women. The sewing and knitting women elected to do in addition to their household duties can be even better appreciated when we consider how much time was already spent on those tasks.

Daughters of the American Revolution Museum: Patterns for slippers and smoking caps in Godey’s Lady’s Magazine, 1859, Peterson’s Magazine, 1863, and The Lady’s Manual of Fancy-Work, 1859, with unfinished slippers, 1850–1870, gift of Inez Armstrong, 3147, and smoking cap, 1840–1870, Friends of the Museum Purchase, 2010.39.1. Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Daughters of the American Revolution Museum: Patterns for slippers and smoking caps in Godey’s Lady’s Magazine, 1859, Peterson’s Magazine, 1863, and The Lady’s Manual of Fancy-Work, 1859, with unfinished slippers, 1850–1870, gift of Inez Armstrong, 3147, and smoking cap, 1840–1870, Friends of the Museum Purchase, 2010.39.1. Courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum

Magazines offered patterns for all kinds of handwork projects featuring embroidery, knitting, netting, beadwork, and other needle skills. The London–based magazines like Godey’s and Peterson’s (begun in the 1830s) offered countless black-and-white and color illustrations for projects to embellish clothing or make accessories and gifts, and patterns could be purchased in stores.

Sewn in America: Making, Meaning, Memory will be on view at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC, from March 15 through December 28, 2024.

Further Reading

- Bohleke, Karin J. “It Was Not Supposed to Turn Out This Way: Sewing and Fitting Errors as Indicators of Social Class,” The Daguerreian Annual, 2015. Academia.edu.

- Emery, Joy Spanabel. A History of the Paper Pattern Industry, Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Kidwell, Claudia Brush. Suiting Everyone: The Democratization of Clothing in America. National Museum of History and Technology, 1974.

Alden O’Brien has a BA in art history from Barnard College and an MA in Museum Studies in Costume and Textiles from the Fashion Institute of Technology. She has been curator of costume at the DAR since 1990, and over time she has been given charge of the dolls and toys, quilts, and most recently the samplers and needlework. She has curated nearly a dozen exhibitions; the next one, combining clothing, quilts, needlework, and household linens, will open in March 2024.