Knitting is one of the most ancient forms of handiwork. Pieces of beautifully designed knitted fabrics have been found in the ruins of ancient Egypt and Peru. What instruments were used is not known, but the stitches are similar to those we do today: knitting and purling.

Knitting in the round or circular knitting is a form of knitting that creates a seamless tube. When working circularly, the knitting is cast on and the first and last cast-on stitches are joined. The knitting progresses spirally in rounds (comparable to rows in flat knitting). The work is done on the outside or the public side of the garment.

There are many advantages to knitting circularly. The weight of the fabric is evenly distributed on the needles, making it less stressful on the arms and wrists. In stockinette stitch, no purling is required—often perceived to be one of the greatest benefits of circular knitting. With a circular needle, there is no need to continually switch from one needle to the next, and stitches will not fall off the back end of needles as they might with double-pointed needles. The construction of garments such as sweaters is significantly simplified because knitting in the round almost entirely eliminates the finishing steps of sewing the sweater together.

The earliest knitting needles had a hook at one end, like a crochet hook, and were made of copper wire. They were filed and shaped by hand. A set consisted of five needles. While one end of the needle was hooked, the other was blunted, and in circular knitting, the hooked ends never touched because the stitches from the left-hand needle were hooked off the blunted end. At some moment in time, the hooked needle was replaced by a smooth-pointed needle. The [earliest] known hooked needles were a set of five found in a Turkish tomb in 1390.

Ancient knitting needles were made of wood, bone, ivory, briar, bamboo, copper, wire, amber, and maybe even iron. Steel needles came later. Knitters themselves made the needles, known as knitting woods, needles, skewers, pins, or wires.

Every sort of material, from steel to powdered milk, is used to make the modern knitting needle or pin today: wood, briar, bone, steel, nickel-plated steel, aluminum, lacquered aluminum, erinoid (also known as galalith), casein, vulcanite, tortoiseshell, and it goes on and on. In addition, every imaginable color is available.

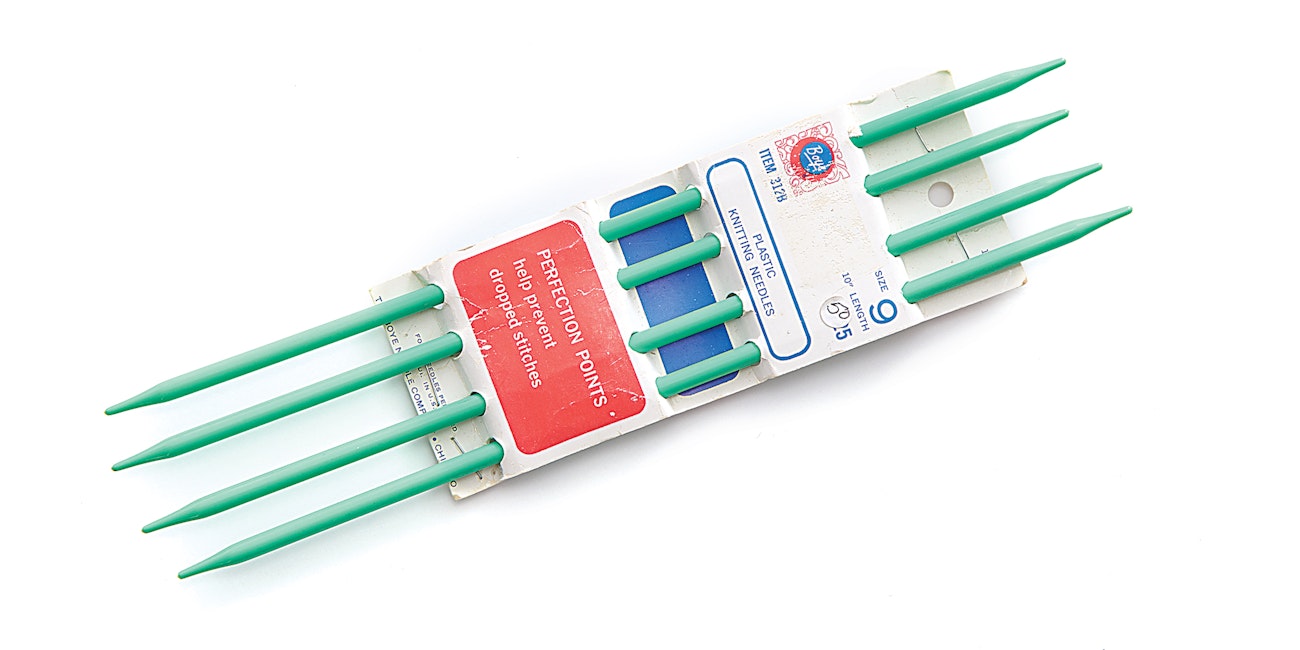

“Perfection points help prevent dropped stitches,” the Boye Needle Company proudly proclaimed on its sets of plastic double-pointed needles.

Double-Pointed Needles

Another type of needle used for circular knitting was the straight double-pointed variety. They were made of wood, bone, ivory, briar, bamboo, copper, wire, amber, iron, and steel in sets of four or five. The needles were often made in blacksmith shops, where steel wire was cut to length, tempered, and then smoothed at the tips to allow knitting from either end. These early needles were heavy, and several lengths were available to use for sweaters as well as socks. A number of fourteenth-century oil paintings, typically called Knitting Madonnas, depict Mary knitting with double-pointed needles.

Circular Needles

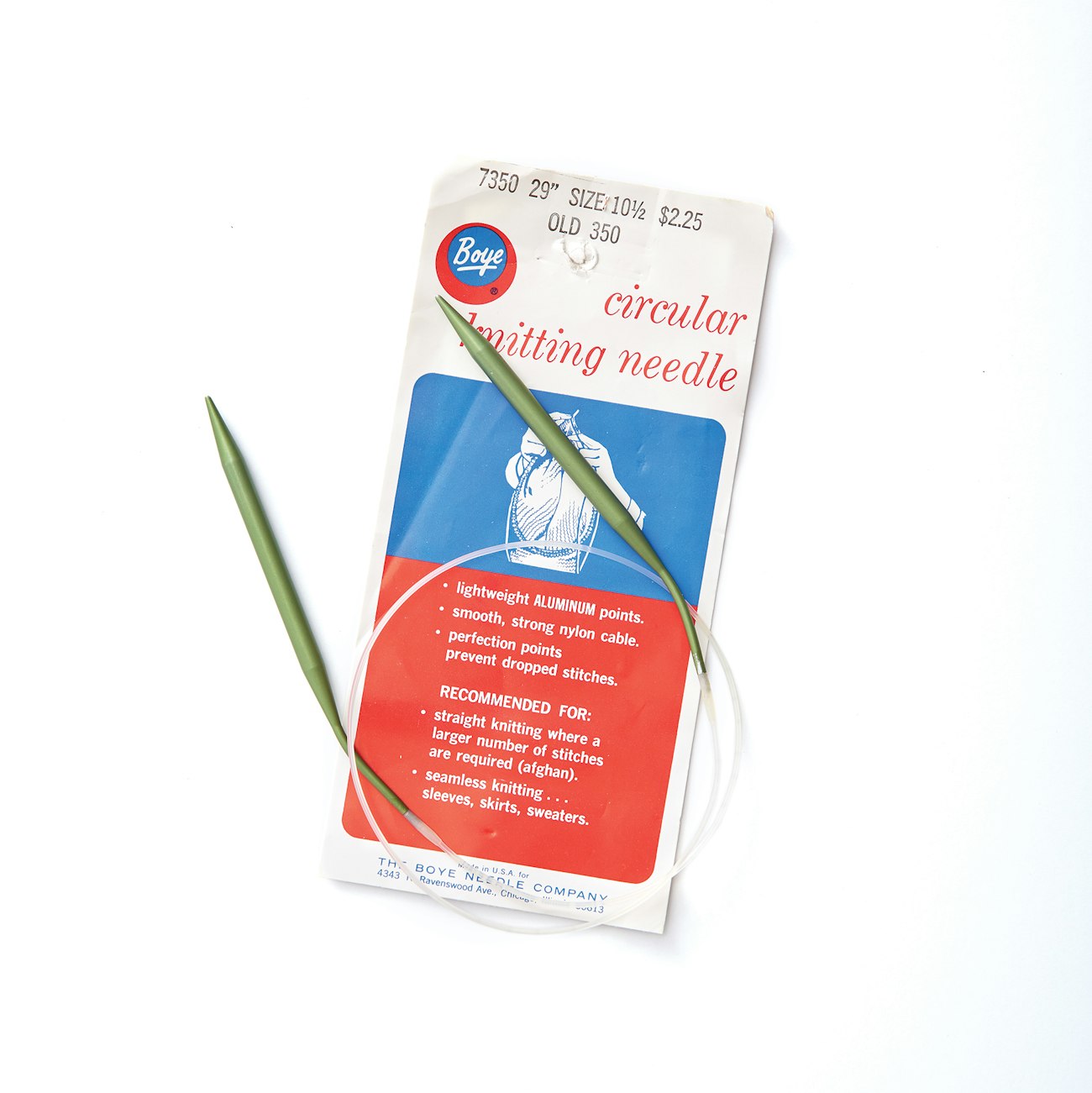

The first U.S. patent for a circular needle was issued in 1918. The circular needle looks like two short knitting needles connected by a cable. The early circular needles were made of steel wire cable with rigid ends. They were somewhat problematic because the joins where the needle tips met the wire would often catch on the knitted yarn, but knitters could “knit the new way” on circular needles, a definite advantage over straight knitting needles.

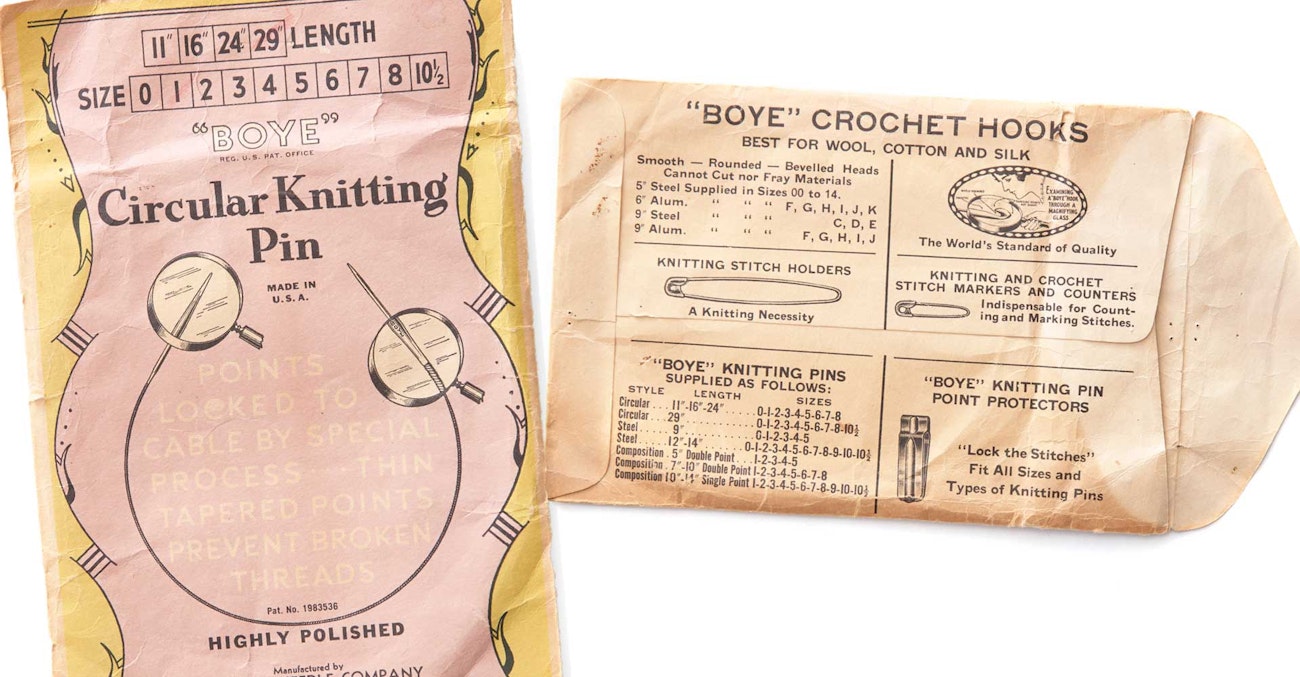

With these new needles, knitters could knit in the round without juggling four or five double-pointed needles. Made in several lengths, circular needles allowed knitters to work a tubular garment such as a skirt or vest in an endless spiral, holding hundreds of stitches on a single pair of needles. Knitting needle manufacturers like Boye marketed the innovation to advanced knitters: “You can’t drop stitches and it’s so much faster and easier.” Boye promoted also circular knitting pins with points locked to a cable by a special process, adding that “thin tapered points prevent broken threads.” Recent technology has developed a smoother join and lighter-weight needle, in lengths 9 inches to 60 inches.

Knitting in the round greatly simplified knitting. The finishing stages of sewing the back, front, and sleeves of a sweater may be almost entirely eliminated in a top-down circular sweater. This is an advantage because wherever seams are sewn, there is less elasticity.

Knitting with steeks is another circular sweater practice. First the sweater is knitted entirely in a circular tube from bottom to shoulders. At the same time, intentional openings (armholes, necks, cardigan fronts) are temporarily knitted with extra stitches. The opening sections are then reinforced by either a crochet pick-up or stitching with a sewing machine. Then the extra stitches are cut to create the opening. A Norwegian friend taught me this technique many years ago. She knits all her sweaters in this way.

Left: Envelope for a “highly polished” circular knitting pin with metal cable, from the Boye Needle Company. Right: On the opposite side of this envelope, Boye listed its circular needle sizes: 11", 16", 24" in sizes 0 to 8, and 29" needles in sizes 0 to 10½.

Two Circular Needles

Some knitters prefer knitting in the round with two circular needles. The concept is incredibly simple: you knit half the stitches on one circular needle and then knit the other half of the stitches using the second circular needle.

Magic Loop

Even though I was taught many years ago to knit socks and mitts using four double-pointed needles, my favorite knitting style today is the magic-loop method. Made popular in 2002, the magic loop creates small-circumference projects on one long circular needle. With this method, you pull out a loop of cable to divide your stitches, usually into two equal parts. Once you divide the stitches, you can use the free needle tip to knit across half the stitches. You then rotate the project and work the remaining stitches.

Using this technique allows you to knit two socks or mitts at the same time. The benefit of this is that your socks will always be the same length, and when you’re done with one sock, you’re done with both socks.

I teach the magic-loop technique and write patterns for socks and mitts using this technique. I do have a few friends who are die-hard double-pointers, and that’s okay. Whatever method you choose, make sure you take pleasure in the process and enjoy your socks.

Boye’s aluminum circular needle retained the “perfection points” but substituted nylon for the cable.

The Problem of Jogs

When knitting in the round, whether it be with double-pointed needles, two circular needles, or the magic loop, the “jog” is always a concern. When knitting stripes, or color designs, a visible step or “jog” between the rounds shows up at the beginning of a new round where you changed colors. There are several remedies for this. This is the one I prefer:

When changing colors or beginning a new stripe, knit one round of new color as usual. As you begin the second round of the new color, with your right needle tip, pick up the right leg of the stitch just below the first stitch of the round and place it on the left needle. (The stitch you are picking up is the first stitch of the last round worked with the previous color.) Knit both the first stitch of the new color and the lifted stitch together. Continue knitting the rest of the round as normal.

The Problem of Laddering

A ladder is a column of extended running threads that are surrounded on either side by normal stitches. They look like the rungs of a ladder. Ladders can occur when using any of the circular techniques. It usually happens in the area between the last stitch of one needle and the first stitch of the next. A ladder can be hardly noticeable or so wide that it appears to be a column of dropped stitches. It is not attractive.

Cat Bordhi taught me the remedy for ladders. When you come to the end of one needle and you are ready to start on the new needle, knit the first stitch and tug. You will notice that it doesn’t tighten very much. The second stitch when knitted is the stitch to tug, and it will tug up very tight. This has fixed my ladder problems substantially.

The stranded-knitting sock project that follows is written for the magic-loop technique starting at the cuff. I didn’t knit both socks at the same time as I often like to do because there would have been too many skeins to work with.

Looking for more knitting history? This article and others can be found in the Fall 2015 issue of Knitting Traditions.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Knitting Traditions Fall 2015. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Further Reading

- Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave, 1987; reprinted 2003.

Eileen Lee has a textile background, working with Levi Strauss & Co. for eighteen years where she was responsible for product development, design, and merchandising. Meadow Farm Yarn Studio in Nevada City, California, is where she has been for the last eleven years, managing the shop; teaching knitting, weaving, spinning, and dyeing; and creating knitting patterns. She now has a studio near her home where she teaches all of the above classes. She is published in several magazines including Knitting Traditions, The Unofficial Downton Abbey Knits, and PieceWork. Her patterns are available on her website mzfiber.com and Ravelry (mzfiber).

Originally published November 25, 2020; updated January 31, 2024.