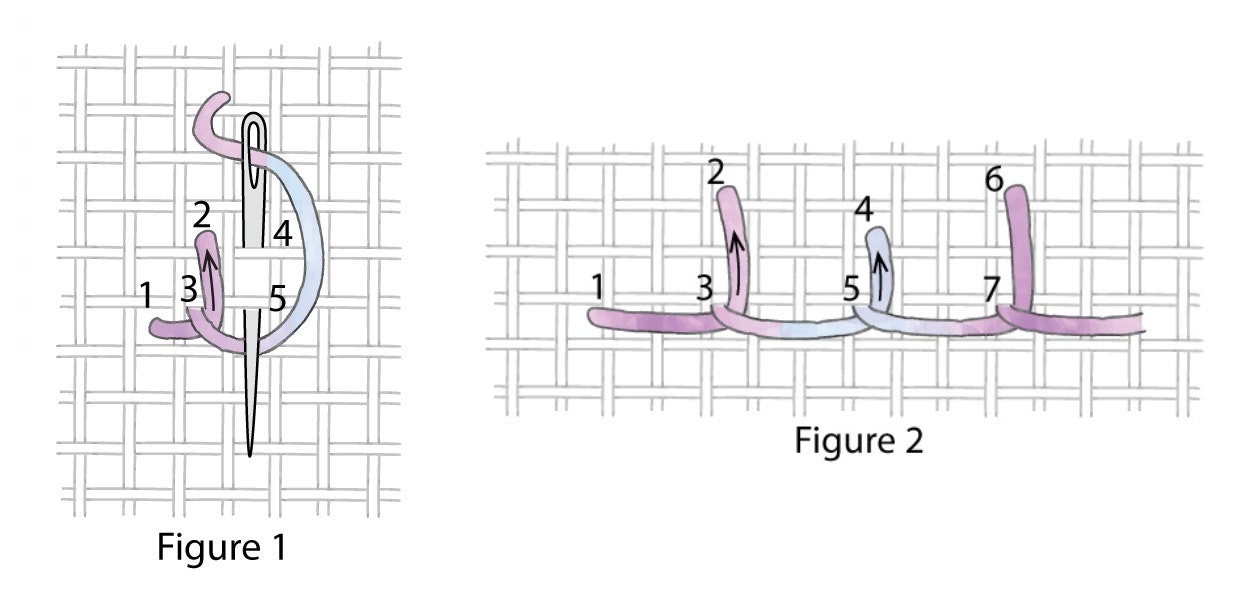

The buttonhole stitch (Figure 1) was historically used to strengthen the cut edges of buttonholes but developed into a decorative surface-embroidery stitch with numerous variations by simply modifying the height, spacing, and angles of the legs and by adding additional stitches to and around the basic stitch. This stitch belongs to the large family of flat and looped stitches and is closely worked together with no background fabric visible between the stitches.

The buttonhole stitch and all of its variations can be worked on either evenweave or nonevenweave (plain) fabrics and with many types of thread or yarn. Its best-known variation is the versatile blanket or open buttonhole stitch (Figure 2), which is simply the buttonhole stitch with its upright legs spaced at varying distances apart. Unfortunately, the buttonhole and blanket stitches have lately become almost synonymous because of their misnaming by some present-day authors and designers, but I strongly feel that the basic distinction between them, leg spacing, should still be acknowledged.

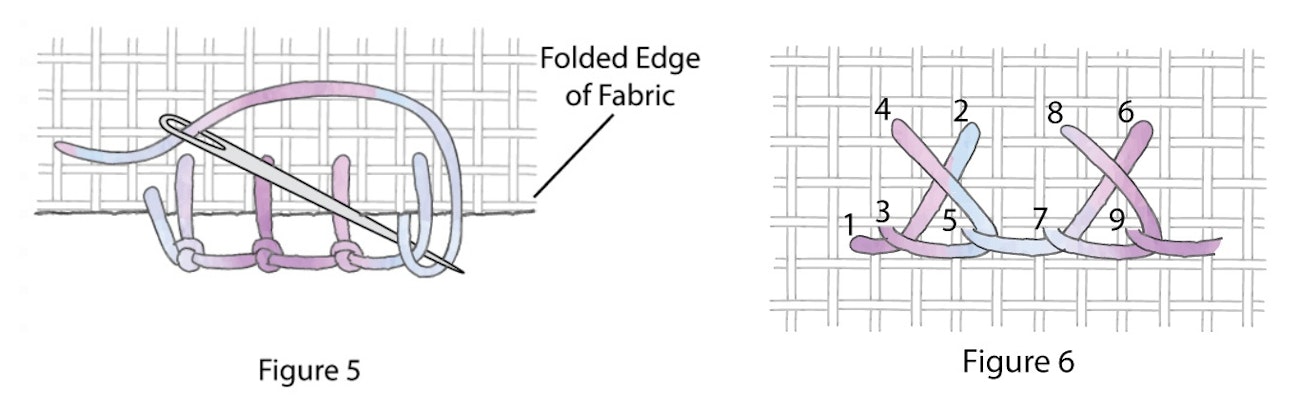

The buttonhole and blanket stitches can be worked horizontally, vertically, and diagonally and can be used for bands (straight, curved, angular, or scalloped), borders, fillings, and individual motifs. The blanket stitch is commonly used to finish the raw edges of blankets and other fabrics as well as to tack down folded hems. These two stitches are extensively used in other embroidery disciplines, including cutwork, needle-made laces from many different countries, Hardanger, crazy quilting, couching ribbon and cords to fabric surfaces, and appliqué work. They are also useful as a pulled stitch to secure cut fabric threads and to serve as an anchoring area for starting and stopping other stitching threads.

These two stitches are well represented on 16th- and 17th-century whitework items (samplers, ruffs, and cuffs), Elizabethan-era clothing, and the colorful traditional band samplers. The buttonhole stitch appeared on the Jane Bostocke sampler (1598), which is the earliest, signed sampler known to date and is presently housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

As I have related many times while teaching sampler classes, one of my fondest early embroidery memories is taking a class at a public school in 5th grade. The home economics teacher taught all of the girls (boys weren’t allowed in sewing classes back then!) the buttonhole and blanket stitches in a couple of minutes at the start of one class period. Then she announced that for the rest of the class period, we would be experimenting with producing our own variations of these two stitches without consulting each other or the classroom’s stitch reference books. Stunned silence reigned for several minutes, then we got busy stitching with an occasional excited comment about our new stitch discoveries. Later we compared our “new” variations, took notes on some of the more unusual or best-liked ones, and generally agreed that this was an extremely fun and enlightening class. Later, we used the newly learned buttonhole stitch to finish some handmade buttonholes and to create dainty belt loops for a dress project.

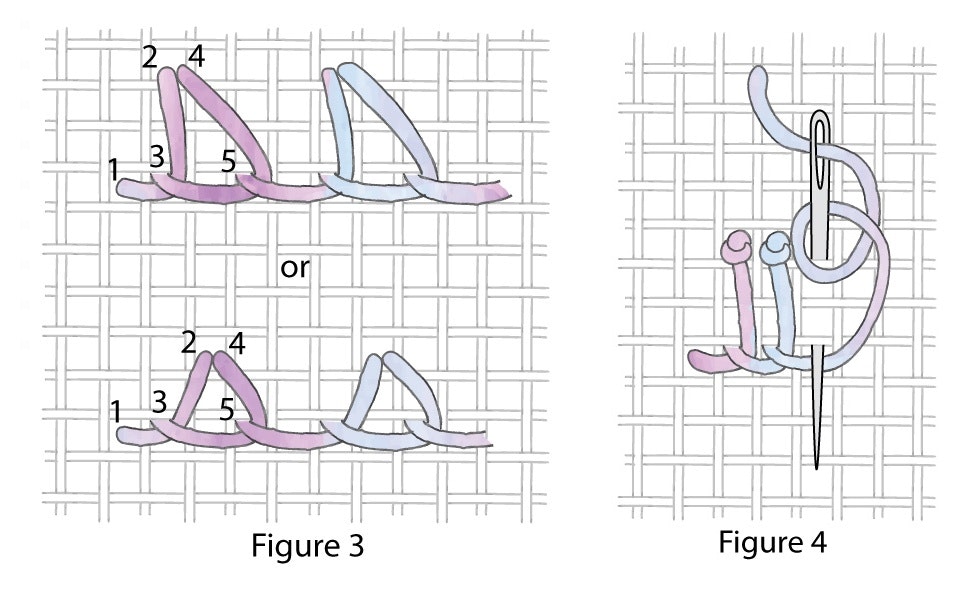

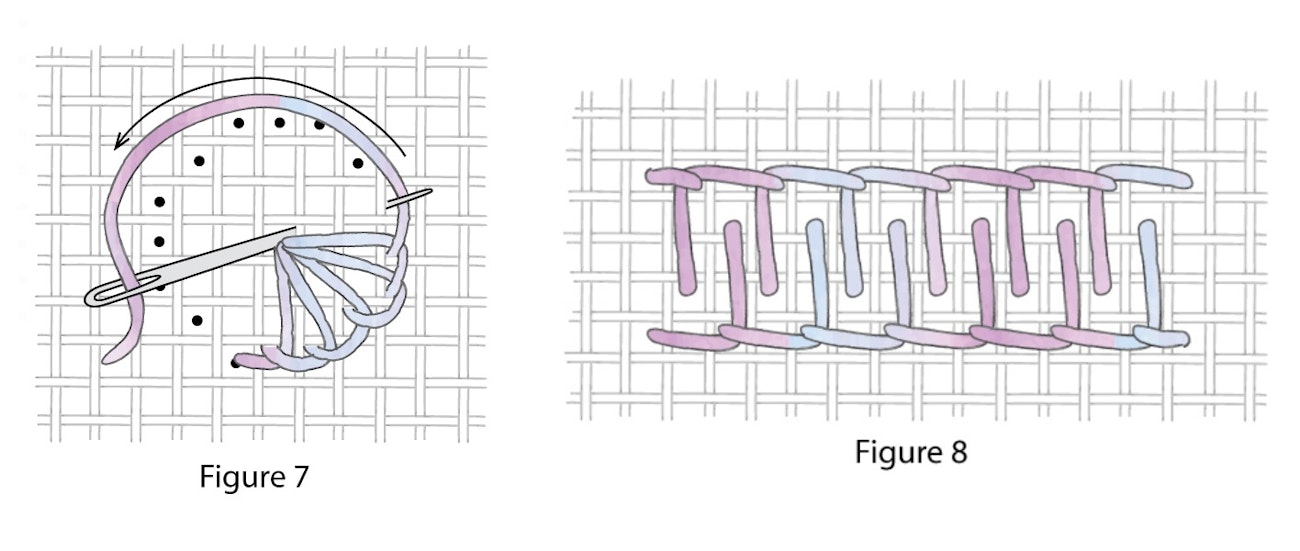

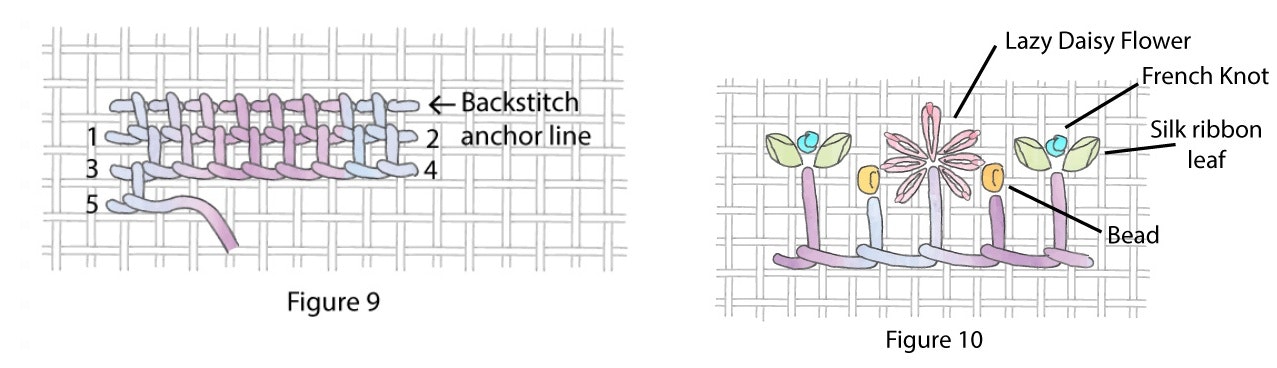

A few of the better known and more widely used variations of the buttonhole and blanket stitches include the closed (Figure 3), open (Figure 4), knotted (also known as knot or Antwerp edging, Figure 5), crossed (Figure 6), buttonhole wheel (Figure 7), double (great for couching, Figure 8) and detached (Figure 9). The detached-buttonhole stitch is worked entirely on the surface of the background fabric except at the beginning and ending of each stitch row. This variation was extensively used in Elizabethan-era raised embroidery. Many additional stitches, buttons, and beads can be added to these basic two stitches (Figure 10) and are especially abundant on crazy quilts, both modern and antique.

The buttonhole and blanket stitches are relatively fast and easy to stitch. Please try one, both, and/or some of their variations on future needlework or sewing projects. I think you’ll find them as fascinating, fun, and useful as I do.

Deanna Hall West is PieceWork’s needlework technical editor; she previously was the editor of The Needleworker magazine.

Originally published July 25, 2018; updated July 25, 2022.