As the nineteenth century drew to a close and the twentieth began, needlework began reappearing in classrooms across Europe and the United States, stitched and knitted by students as young as kindergarten age. Like those of scientific, artistic, and other academic fields, theories about the education of young children were being revolutionized. Innovators such as Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852) in Germany and Maria Montessori (1870–1952) in Italy were rejecting teaching by passive, rote memorization of facts and acquisition of academic skills in favor of a new type of learning achieved through direct and concrete experience.

Needlework, a key component of the curriculum for girls and young women in previous centuries, found a new role in these new, “object-based” curricula. Along with such hands-on activities as carpentry and cooking, embroidery and knitting were introduced to young students not as vocational training but as a means of awakening and shaping their intellect.

Kindergarten 1837

Froebel, a physical scientist as well as an educator, opened his first school for young children in 1837, declaring it a Kindergarten, a “children’s garden,” in which the spirit and intellect of students would be gently encouraged and cultivated through direct experience. Seeking to harness children’s natural urge to play and explore their environment, he built his program around a series of about twenty manipulative toys and activities, which he termed “gifts.” Froebel designed the program to embody aesthetic values such as color harmonies and geometric principles through which students would experience and appreciate the natural harmony of the universe. His gifts began with a simple set of six colored balls of crocheted wool (the First Gift) and progressed to ever more complex activities such as modeling with clay, creative paper folding, and weaving. Decorative stitching with colored thread, which produced work resembling central European folk embroidery, was Froebel’s Twelfth Gift.

Needlework projects began with simple, repetitive lines stitched through gridded or punched paper cards and advanced to complex patterns of crosshatched color. Stitchers gained an intimate connection with geometric and color relationships and textures, which Froebel believed would foster his students’ understanding of the fundamental principles shaping their cultural and natural environment.

Dewey Laboratory School 1896

As part of the Progressive Education Movement, John Dewey (1859–1952) and his wife Alice (1858–1927) aspired to create a cooperative community within their classroom, in which students learned through self-motivated explorations and activities. While setting up their experimental classroom at the University of Chicago, the Deweys were told by a dealer that the type of desks they requested was not available—the industry standard was a desk “designed for listening, not for working.”

John Dewey believed that early school experiences should reflect students’ home life and be focused on problem solving; that academic learning would be an outgrowth of their involvement in real-life occupations. Thus, his school had supporting workshops: a kitchen, a carpentry room, and a sewing room. In the sewing room, the children did needlework, and spun, dyed, and wove cloth. The needlework that the students designed and created addressed all four of what Dewey considered the “natural impulses” in children that motivate learning: the constructive impulse (to make things), the social impulse (to cooperate with and learn from others), the investigative impulse (to explore the nature of things), and the expressive impulse (to design things).

1907 Casa dei Bambini

Like Froebel and the Deweys, Maria Montessori believed in the value of self-directed activity and in training the senses through the handling of physical objects. She began her career teaching “unteachable” mentally challenged children. Her success with these pupils led her to question the lack of progress made by children attending standard schools in Italy. She concluded that the rote memorization and harsh discipline used in these schools stifled development, whereas the techniques that she had developed encouraged it. Montessori continued to develop her teaching method at a school for the young children of poor families living in newly constructed tenements in Rome, Casa dei Bambini (“Children’s Houses”). She presented her method to the world at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco, where students from the local community attended class within a glasshouse exhibit.

The environment within Maria Montessori’s classroom allowed students to choose which materials they would work with while keeping within boundaries of safe and appropriate behavior. Children mastered everyday, real-life tasks such as gardening and cooking and worked with materials that allowed them to see and correct their own mistakes.

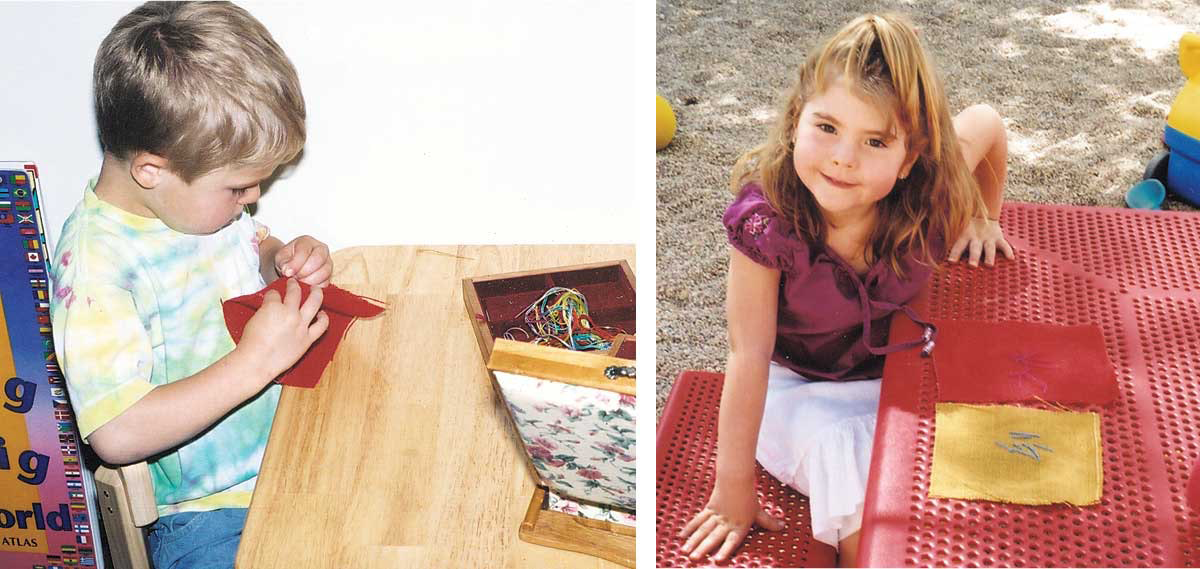

Needlework found a natural place within the Montessori classroom. Stitching not only allowed children to gain competency while wielding a real tool and producing visible results, it also developed hand-eye coordination and spatial awareness, which would prepare them for later academic work such as writing and mathematics.

Die Freie Waldorfschule, 1919

In 1919, the Austrian philosopher and scientist Rudolph Steiner (1861–1925) opened his Freie Waldorfschule (“Independent Waldorf School”) for the children of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory workers in Stuttgart, Germany. This school was the first of many Waldorf schools that eventually opened throughout Europe, Japan, and the United States. Steiner’s aim was to encourage a lifelong love of learning in his students through the use of the arts and by engaging all of their senses with each classroom project.

From these earliest days onward, crafts fulfilled an essential role in the Waldorf curriculum. Steiner saw this “handwork” as the bearer and cultivator of human culture; he believed that by creating art with their hands, students would develop their powers of reason, conceptualization, and imagination, as well as their manual dexterity and attention to detail.

All students, from first grade up through high school, did handwork, which included a variety of needlework. The youngest students began by knitting with their fingers; as they grew older, students practiced knitting with needles, weaving, constructive sewing, and embroidery. Steiner’s intent by emphasizing needlework and other crafts was not to produce professional artisans but to instill in his students a sense of competence and thereby confidence. When students create purposeful and beautiful objects with their own hands, Steiner asserted, they intimately experience the intellectual and spiritual concepts of beauty and meaning. “We are then working on the spirit of the child,” he said in 1921, “and often more truly so than when we teach him subjects that are generally thought of as spiritual and intellectual.”

Sam Kaplan and Mary Buchanan, shown with their embroidery, were Montessori students at Hope School in Fort Collins, Colorado, in 2004. Photos by Linda Moore

Preschool and Kindergarten in the Twenty-First Century

While preschool pedagogy continues to be a topic for debate, and philosophies of classroom teaching vary widely, the legacy of the hands-on approaches instituted by Froebel, the Deweys, Montessori, and Steiner continues. Kindergarten classrooms, though they may not closely resemble Froebel’s spiritually inspired “children’s garden,” are a standard of public school education. Montessori and Waldorf schools abound. Nearly all contemporary forms of early childhood education recognize the value of multisensory experience in developing analytical skills, coordination, and confidence. In this connection, the needle arts continue to be a source of competence and confidence to our society’s youngest hands and minds.

Interested in learning more about needlework education? This article and others can be found in the September/October 2004 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including September/October 2004. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Brosterman, Norman. Inventing Kindergarten. New York: Abrams, 1997.

- Wolfe, Jennifer. Learning from the Past: Historical Voices in Early Childhood Development. Mayerthorpe, Alberta, Canada: Piney Branch Press, 2000.

Linda Moore works at the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery.

Originally published April 5, 2020; updated April 3, 2023.