I’ve always liked the color blue, but recently I’ve discovered fascinating research on the concept of the color blue throughout history. Apparently, because true blues are so rare in nature, many ancient cultures didn’t have words for blue—it’s almost like they couldn’t see it. Some research suggests that perhaps the way human eyes evolved meant these cultures literally didn’t see blue, or perhaps they perceived blue as different shades of other colors. (Note: As far as I can tell, there’s no real research on the history of the color blue in the Americas, although we do know a bit about the history of blue in Africa and the Pacific Islands. Blue dyes and pigments were used throughout the Americas before European contact, so it could very well be that the concept of blue developed there long before Egypt—sadly, there’s no way to know for certain.) The truth is, we have no idea why blue is such a recent concept, but what we do know for sure is that one of the first cultures to have a concept of the color blue was that of ancient Egypt, and for that we can probably blame their use of woad.

Woad it a plant in the mustard family, and when harvested and treated properly, the leaves can be used to create both a blue dye and a pigment. (You can read about the difference between the two here.) According to Jenny Balfour-Paul in her book Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans, woad has an unusual chemical make-up that allows it to be used both as a dye and a pigment. As a dye, it was perfect for dyeing fabrics, and as a pigment it worked well for paint and ink. Now if this sounds a bit like what some folks like to call “true indigo” (indigo plants native to India, Japan, and the Americas), that is because the chemical in woad that creates the blue dye is the same chemical found in indigos—just in a smaller concentration. (Interestingly, the murex sea snail also produces this same chemical along with a red to create its trademark purple.)

The plant is native throughout Eurasia, and as far as historians and archaeologists can tell, ancient Egyptians were the first to realize its potential as a dye around 2500 BCE. With the use of woad came words for the color blue. Eventually, woad and the color blue spread further throughout Eurasia during the rest of the Late Paleolithic and into the Iron Age. By the Medieval period, woad was a fairly common dye, and the plant was cultivated for that purpose.

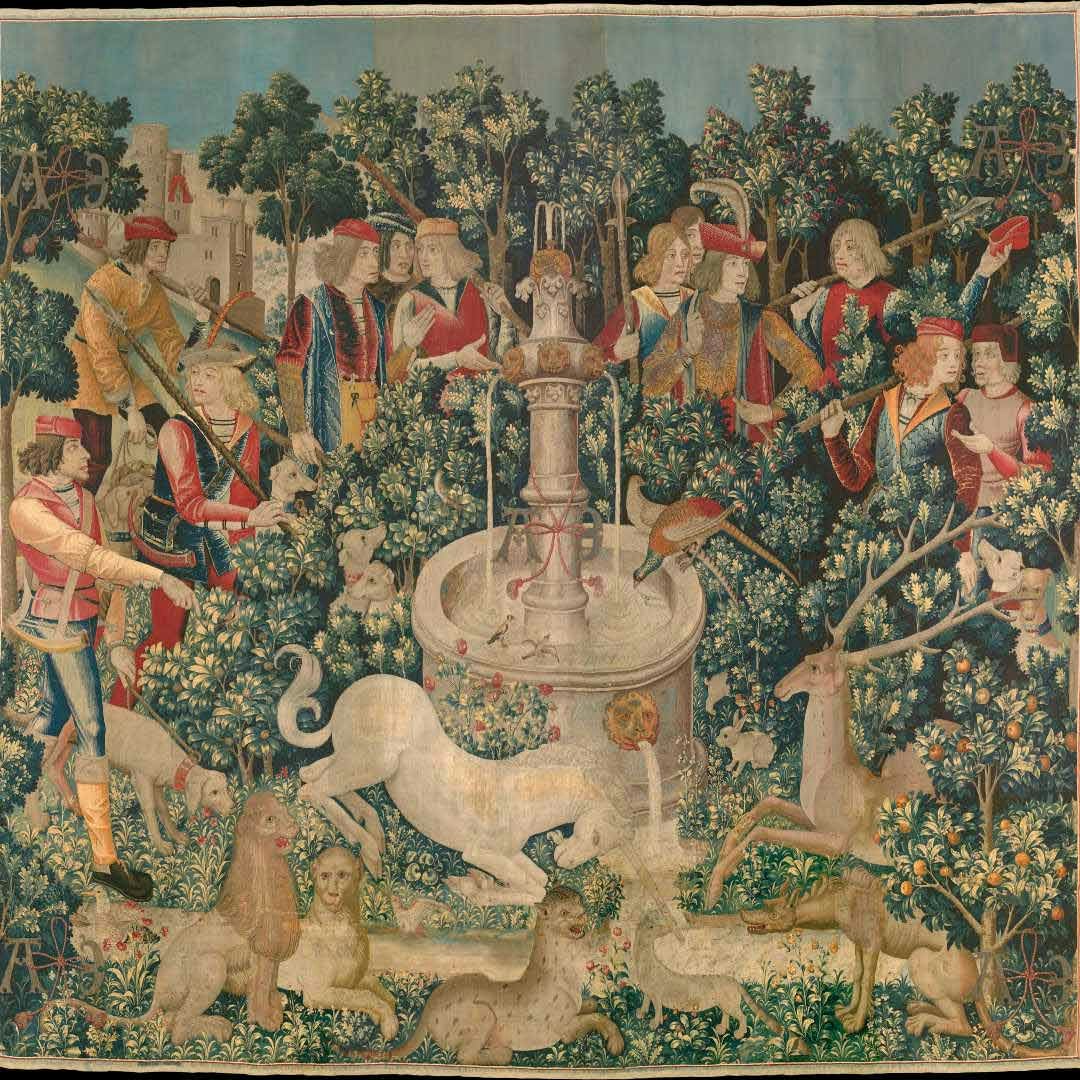

The blue in the famous Unicorn Tapestries was achieved using a blue dye. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Eventually, the small concentration of pigment in woad led to the waning of its popularity. The “true” indigo plants have a significantly higher concentration of this chemical, which means not only can you get more dye and pigment from an indigo plant versus a woad plant, but you can also get a deeper shade of blue. When routes from India opened up, it allowed for the importation of true indigo; of course, those invested in woad didn’t go without a fight. They (falsely) claimed indigo caused yarns to rot, and indigo was banned for a time in both Germany and France. The bans didn’t last, and today when we talk of natural blue dyes, most of us refer to indigo first and foremost.

Woad is still an excellent blue dye, although if you’re thinking of expanding your dye garden this year to include it, you might think again. In many places, woad is considered invasive and a noxious weed. You can read more about growing woad in a dye garden and the caveats around it here.

From the original color blue to a noxious weed, it’s been a long road for woad.

Christina