This special guide from PieceWork invites you on a winter expedition. You can visit winter markets, ponder Polar exploration, and even ride in a chilly open carriage. Even if the thought of warm woolies leaves you cold at the moment, read on to enjoy this brief visit to some very chilly spots.

In this collection, we’ve gathered five noteworthy excerpts from the PieceWork archive that explore this month’s winter theme. These include:

- The unlikely tale of Edith (Jackie) Ronne and how she came to be the first lady of Antarctica

- How a balaclava helped Sir Douglas Mawson explore our southern-most continent

- A stop at Jokkmokk Winter Market, the largest and oldest continuously held winter festival north of the Arctic Circle

- Plus, two mitten patterns to download: one based on a pair of Sami mittens and the other on carriage mittens

As our gift to you, we've made this All Access guide free for everyone to access. We hope you enjoy these feature articles and patterns that we've carefully curated especially for you.

~ The Editors of PieceWork

Edith (Jackie) Ronne: First Lady of Antarctica

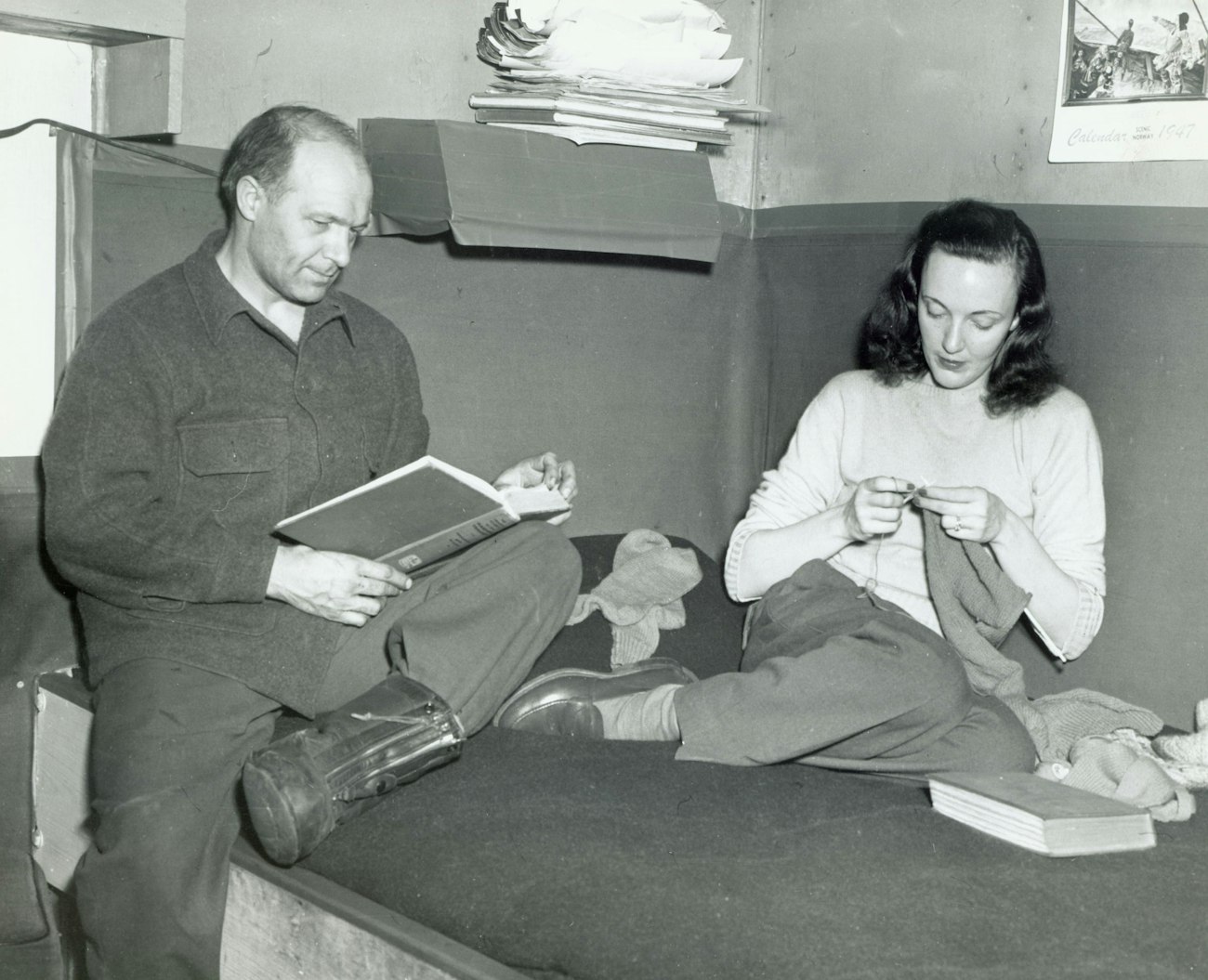

Finn and Jackie Ronne in their living quarters. Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1947–1948). Photo courtesy of the Ronne Family

Finn and Jackie Ronne in their living quarters. Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1947–1948). Photo courtesy of the Ronne Family

The woman who became known as the First Lady of Antarctica almost did not make it to the Antarctic. Edith (Jackie) Ronne, the wife of famed explorer Finn Ronne, had intended to say goodbye to her husband in Beaumont, Texas, before he departed on a fifteen-month expedition to the frozen continent—the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (1947–1948). For her trip from Washington, D.C. to Beaumont, Jackie packed only a good suit, a good dress, a skirt and a sweater, nylon stockings, and high-heeled shoes.

Finn and Jackie had planned that Jackie would handle background work for the expedition from their home in Washington, D.C., where Jackie worked in the U.S. State Department’s Division of International Information and Cultural Affairs. When insurance issues delayed the expedition’s departure from Beaumont, Jackie agreed to accompany her husband to Panama to discuss the matters she would have to take care of while he was away.

On the way to Panama, Finn—whose native language was Norwegian—realized that Jackie’s excellent writing skills would be required to prepare dispatches and articles on the expedition’s behalf. According to Jackie, when Finn told her that he wanted her to accompany the expedition to the Antarctic, “I just blew an entire gasket and said there is no chance I am going to do that! I have a very good job with the State Department. No woman has ever gone on an Antarctic expedition before. I’m not interested in the publicity of going. . . .”

But Finn was an extremely persistent man, and, stop-by-stop, he cajoled Jackie into accompanying him from Panama to Valparaiso, Chile, where Jackie finally agreed to join the expedition. But not wanting to be the only woman in the expedition party, Jackie asked that another woman come along, and Jennie Darlington, the Canadian wife of the expedition’s chief pilot, was added to the party. Jackie became the first American woman to set foot on the continent of Antarctica, and Jackie and Jennie became the first women to winter over in the Antarctic.

In Puentas Arenas, Chile, the expedition’s last stop en route to the Antarctic, Jackie—an avid knitter—went in search of some knitting wool. She found a shop where she could purchase either American- or Chilean-produced wool. She chose the Chilean wool because it was different and it was cheaper. But the shop had no knitting needles or knitting patterns. Another English-speaking shopper overheard Jackie say that she was going to be spending a year in the Antarctic, and intrigued by Jackie’s story—and perhaps horrified at the prospect of a knitter being stranded for a year with copious amounts of yarn but no knitting needles—the other shopper ran home and retrieved her own collection of knitting needles, which she gave to Jackie. In later years, Jackie repeatedly lamented that she had been unable to send a message of appreciation to that gracious knitter, because Jackie had neither her name nor address.

During her months in the Antarctic, Jackie knitted mittens, headbands, hats, scarves, sweaters, regular socks, and after-ski socks (with added innersoles), with only her memory to guide her in turning a heel. Some of these knitted items are on display in the National Museum of the United States Navy (U.S. Navy Museum) located at the Washington Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.

Mimi Seyferth

The Mawson Balaclava

Hand-tinted photograph of members of the British, Australian, and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929–1931. Sir Douglas Mawson, the only one wearing a balaclava, is in the second row, third from right. Photo courtesy of South Australian Museum

Hand-tinted photograph of members of the British, Australian, and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929–1931. Sir Douglas Mawson, the only one wearing a balaclava, is in the second row, third from right. Photo courtesy of South Australian Museum

Sir Douglas Mawson (1882–1958), Australian geologist, explorer, and academic, was one of the first scientists to explore the continent of Antarctica. He accompanied Ernest Shackleton (1874–1922) on the British Antarctic Expedition (1907–1909) and later commanded the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911–1914) with the purpose of charting the coastline directly south of Australia. Upon his return, he was greeted as a national hero and knighted. He made a second Antarctic expedition (1929– 1931), after which he became a professor of geology at the University of Adelaide.

A photograph of Mawson wearing his Antarctic expedition balaclava shows a man well prepared for extreme environments. In the group photograph taken in 1930, he is the only man wearing a balaclava drawn down over his face, while his seventeen fellow scientists are all wearing standard-issue headgear provided by the Jaeger clothing company.

Mawson’s balaclava is handknitted from different colors of wool. What looks like a simple garment made to protect the explorer against extreme conditions is, on closer inspection, a work of fine detail and excellent workmanship, created with great care and thought.

Although there is no proof, it is believed that the balaclava was made by his wife, Paquita Mawson (1891–1974). She became engaged to Mawson at the age of nineteen, shortly before he left on his first Antarctic expedition in 1911; they married shortly after his return in 1914. Is it coincidence that their wedding took place in a town called Balaclava in Victoria?

Ansie van der Walt

Jokkmokk Winter Market

Per Kuhmunen leads the reindeer caravan down the main streets of Jokkmokk during the town’s Winter Market. Per’s čuipi (hat) has the large, red pom-pom (diehppi) on top. Jokkmokk, Sweden. 2011. Photo by Petter Johansson and courtesy of Jokkmokk Winter-Market/ Jokkmokk Municipality

Per Kuhmunen leads the reindeer caravan down the main streets of Jokkmokk during the town’s Winter Market. Per’s čuipi (hat) has the large, red pom-pom (diehppi) on top. Jokkmokk, Sweden. 2011. Photo by Petter Johansson and courtesy of Jokkmokk Winter-Market/ Jokkmokk Municipality

The Jokkmokk Winter Market in Jokkmokk, Sweden, is the largest and oldest continuously held winter festival north of the Arctic Circle. Sweden’s King Carl IX (1550–1611) established the Jokkmokk market day by royal decree in 1605 as a means of officially collecting taxes from the Sami people, providing a venue for trading fur and leather goods, and establishing a post where the Lutheran priests could baptize, marry, and confirm the Sami people. It has remained an important Sami gathering place and market. (The Swedish Sami parliament uses the self-name “Sami” for the people, but in other areas it is spelled Sámi or Saami.)

The Sami are the indigenous people of northern Fennoscandia and have lived in this region of Sweden for thousands of years. (They have also been called “Lapps”; today, this term is considered an ethnic slur.) The Sami homeland— a land the Sami refer to as Sábme—extends across the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. Today, about 100,000 Sami live in Sábme, about 15,000 of them in Sweden.

[. . .]

Along with his family, Per Kuhmunen is one of the most photographed and easily recognizable people from the Jokkmokk Winter Market. I have found photographs of him in five different gákti [traditional clothes] that his wife, Dagny, has made, each with a different foundational color— red, green, black, medium blue, and light blue. She made them all by sewing machine with wool cloth and trim. In addition, she handsewed the older, traditional reindeer fur gákti, the best choice for the coldest weather. Per has two different belts he wears with these traditional jackets: a black one from the Jokkmokk region and a white one from Juhls Silver Gallery in Kautokeino, Norway. One of the most recognizable textiles from this area of the North Sami region is the man’s traditional cap or čuipi. It is fantastic! Perhaps the cap itself is fairly normal, but it is overshadowed by the large, red pom-pom (diehppi) on top. In my conversation with Dagny, the question I was most anxious to have answered was how many balls of yarn it takes to make the hat’s pom-pom. The answer was overshadowed by the chore of its making. “After I am done with it, I try not to think about it,” Dagny said. According to tradition and the stories Dagny was told as a girl, the size of the pom-pom indicated a man’s wealth—that is, the number of his reindeer.

I learned long ago that it is rude to ask Sami how many reindeer a herder owns; it is equivalent to asking an American acquaintance how much money he or she has in the bank. However, perhaps it is hard not to brag a little bit. When Dagny was making a pom-pom for Per’s hat, he asked her to make it “very large.” I pressed her, “Exactly how many balls of yarn did you use?” The pom-pom is so large that she couldn’t put it in quantities of balls. “About 1 to 2 kilograms [3 to 4 pounds] worth,” she said. That represents a lot of reindeer and makes for a very heavy hat!

Sami gákti shoe bands also end in a pom-pom, but nothing as large as the one for the hat. Shoe bands or shoelaces are woven on a narrow loom and wound between the top of the shoes and the bottom of the fur leggings. They serve to keep the top of the boot closed and the snow out. Socks are not traditional in the gákti. Instead, women harvested sedge grass, dried it, and used it as liners for sweat absorption and as insulation for both boots and reindeer fur mittens. Knitting only became a part of the Sami gákti in the mid-1800s. Borrowed from the ethnic majority around them, knitting was almost exclusively used for hand garments. Reindeer fur mittens are still the best insulators and protection from the wind at the coldest time of winter, but handknitted mittens make a more comfortable liner against the hard seams than the sedge grass does. I have been told as well that lassoes (used on reindeer) glide more easily through handknitted mittens than through fur mittens. Although work mittens are usually one color without decoration, festival mittens can be quite a showcase of color and skill, like Per’s Karesuando mittens.

Laura Ricketts

Pattern Download: Karesuando Mittens to Knit

Karesuando Mittens to Knit was originally published in PieceWork, November/December 2015. Photo by Joe Coca

Karesuando Mittens to Knit was originally published in PieceWork, November/December 2015. Photo by Joe Coca

This mitten pattern is based on a pair of Sami mittens I saw in Lulea, Sweden, at the Norrbottens Museum. It is a typical mitten from Karesuando, which is at the farthest northern tip of Sweden. These mittens were originally meant for men. Both Per and Dagny Kuhmunen come from this area.

Unlike many of the other Sami mittens I have seen, these Karesuando mittens have a staggered mitten-tip decrease. That is, instead of decreasing at the edges of the mitten, which creates flat mitten fronts, the knitter staggers decreases evenly across the rounds up to the red tips. At that point, regular decreases create a slightly swirled tip.

The Karesuando mittens I observed at the museum had patterned thumbs, but Per Kuhmunen’s Karesuando mittens have a thumb in solid blue. This is not only easier, but eliminates the constriction that can occur much more readily in small-circumference stranded work. Download and enjoy your free copy of Karesuando Mittens to Knit in our library.

Laura Ricketts

Pattern Download: Vermont Carriage Mittens

Donna Druchunas knitted loops with a second strand of yarn carried along as the knitting was worked, then cut, brushed, and trimmed them to create the finished texture in her warm and fuzzy Vermont Carriage Mittens. Photo by Joe Coca

Donna Druchunas knitted loops with a second strand of yarn carried along as the knitting was worked, then cut, brushed, and trimmed them to create the finished texture in her warm and fuzzy Vermont Carriage Mittens. Photo by Joe Coca

Stopping by woods on a snowy evening, a lady riding in a carriage would need something especially warm to protect her hands from the bitter cold of winter. In 1850, the St. Johnsbury railroad station in Vermont was a stop on the new line that was built from Boston to Montreal. The town of St. Johnsbury was small but home to several new industrial businesses. It was the center of what would come to be known as the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. Less than 50 miles (80 km) south of the Canadian border, it was also cold.

When I stopped off for a latte at the Freighthouse Coffee Shop in Lyndonville, about 3 miles (5 km) north of St. Johnsbury, I discovered that a small gift shop and museum was tucked away upstairs from the restaurant. I found myself looking at a small collection of nineteenth-century items from the local area. Among them was a pair of mittens with a shaggy surface made of individual pieces of yarn.

The description of the mittens, handwritten on an index card, didn’t explain anything about their unusual construction. “During the winter when women came into the [St. Johnsbury, Vermont] station and had to take a carriage to another town they were given these mittens to keep their hands warm.” Download your free copy of the Vermont Carriage Mittens pattern in the PieceWork Library.

Donna Druchunas

Resources

- Druchunas, Donna. "Vermont Carriage Mittens." PieceWork January/February 2016.

- Ricketts, Laura. "Jokkmokk Winter Market." PieceWork November/December 2015.

- Ricketts, Laura. "Karesuando Mittens to Knit." PieceWork November/December 2015.

- Seyferth, Mimi. "Edith (Jackie) Ronne: First Lady of Antarctica." Knitting Traditions Spring 2015.

- van der Walt, Ansie. "The Mawson Balaclava." Knitting Traditions Spring 2015.