Several years ago (2015, actually), I was in the Peruvian highlands working on a book with photographer Joe Coca. We were documenting some textile techniques and had asked young people from some of the villages to show us, and the camera, how to do them. Spinning, weaving, knitting, embellishing—these kids, who ranged in age from about 10 upwards, were so skilled and so willing to share. We knew (because we asked) that most of them didn’t envision spending their lives in their home villages, though. They loved their families and traditions, but they wanted more to look forward to than the bare-bones poverty that staying might mean.

How were these kids thinking about their past and their future as they approached decision-making times in their lives? We decided to ask, in a roundabout way. Here’s what we did. We gave the Young Weavers’ Association in each of 10 villages a bunch of disposable digital cameras and asked the members to go take pictures of what they valued, of what they thought would be important to show the outside world, of what they thought was important to keep. Then we promised we would use their images to make a book that they could share with their elders.

Girls from Santo Tomás, Chumbivilcas, interview an elder in their remote village. The traditional costume here is reverse appliqué rather than handwoven.

Girls from Santo Tomás, Chumbivilcas, interview an elder in their remote village. The traditional costume here is reverse appliqué rather than handwoven.

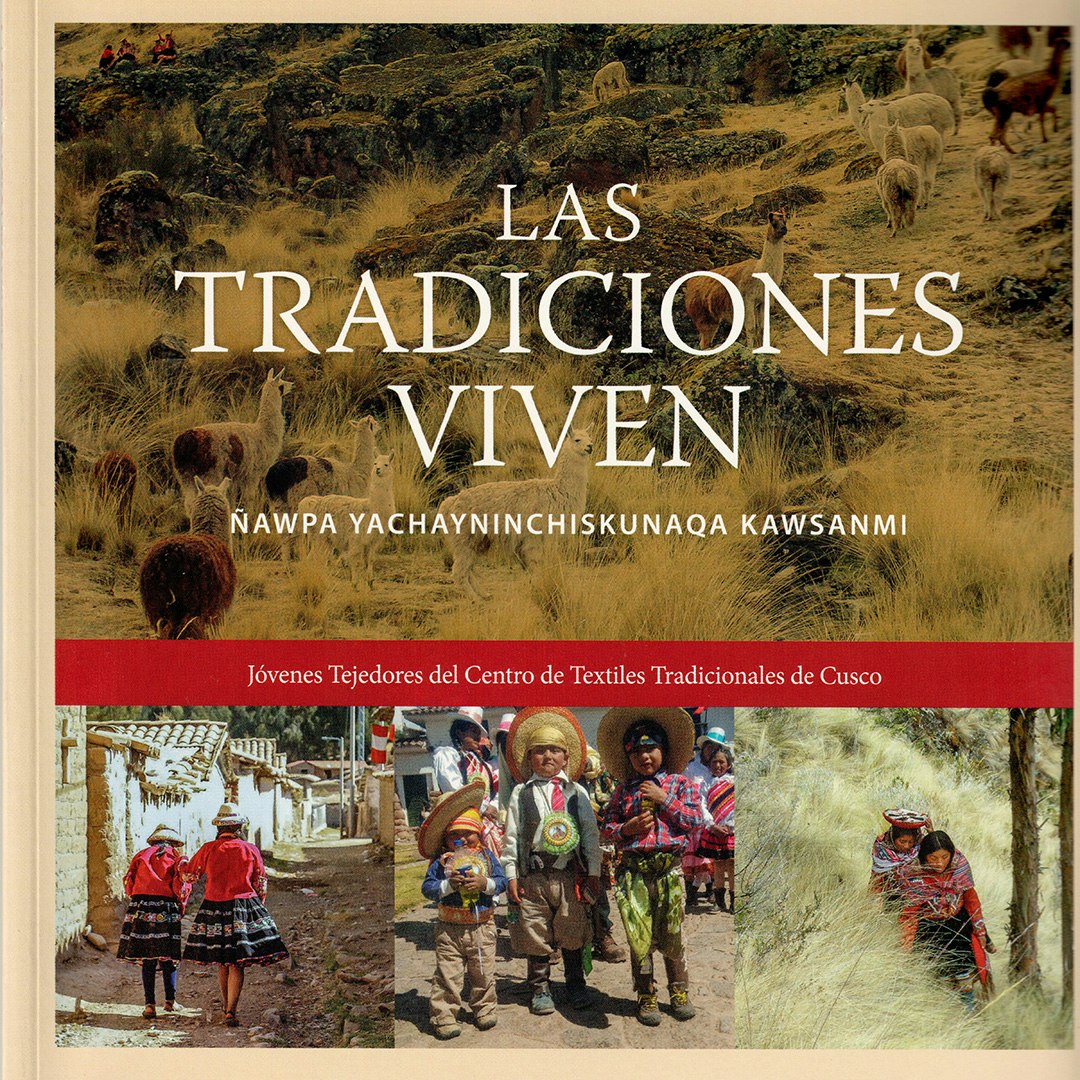

And that’s how Las Tradiciones Viven, or Ñawpa Yachayninchiskunaqa Kawsanmi, came to be. After the kids got over the fun of taking many selfies of themselves and their friends all dressed up in their best traditional outfits, they gave serious attention to the task at hand. They took close looks at the crops, the livestock, the rituals and celebrations, the family life. They recorded things I’d never seen before.

Boys interview an elder in Mahuaypampa, a heavily agricultural village.

Boys interview an elder in Mahuaypampa, a heavily agricultural village.

One group of kids from a very high Andean village actually photographed and documented a couple hundred of the varieties of potatoes for which their village is known. Of course, we couldn’t show them all in the book, but we showed a lot—and their pride in this special contribution shines through.

Spinning is the first hand skill most children learn in Accha Alta, the highest village in the CTTC network, which is known for its potatoes.

Spinning is the first hand skill most children learn in Accha Alta, the highest village in the CTTC network, which is known for its potatoes.

Other kids in other villages photographed Inca and Huari ruins that are off the beaten path but special to their communities. One documented a six-year-old boy’s first haircut, a special ceremony that I had heard of but had never hoped to see. It’s a big deal!

In the photos, there were two versions of a wedding: the modern white lacy one that some couples choose now, and the traditional one that features the best of handwoven costumes and is lavish with flowers. There are wildly energetic festivals with parades and street dancing. There’s the annual holy pilgrimage up Mount Ausangate to the glacier, complete with a bit of nontraditional graffiti. There’s a shaman creating an offering to be burned for the fertility goddess Pachamama. There’s a funeral.

Teenagers from Pitumarca make the annual pilgrimage to the ice fields of sacred Mount Ausangate. Did they leave their initials in the snow? We don’t know. But they know how to make world-class sling braids.

Teenagers from Pitumarca make the annual pilgrimage to the ice fields of sacred Mount Ausangate. Did they leave their initials in the snow? We don’t know. But they know how to make world-class sling braids.

We met with 130 young weavers one year after giving them this assignment. We did a little presentation of how a book gets made: the editing, the designing, the printing. We asked them what they wanted to call it. We asked if it should be in English. No! Not English! They wanted it in Quechua, or at least in Spanish.

Two young weavers in Patabamba test their camera.

Two young weavers in Patabamba test their camera.

We compromised on Spanish with an English translation in the back and Quechua sidebars. (Quechua is hard to write. Even native speakers don’t agree on how many vowels it contains, for instance.) We showed them a bunch of the best photos from their explorations and let them flag the ones they liked best. (Their cover choice: a very brown landscape with many llamas off in the distance. I would never have picked that, but it certainly was important.) We went off with their notes and photos, and we made a book. We had enough printed for each child to have their own copy and for copies to be sent to their villages’ archives.

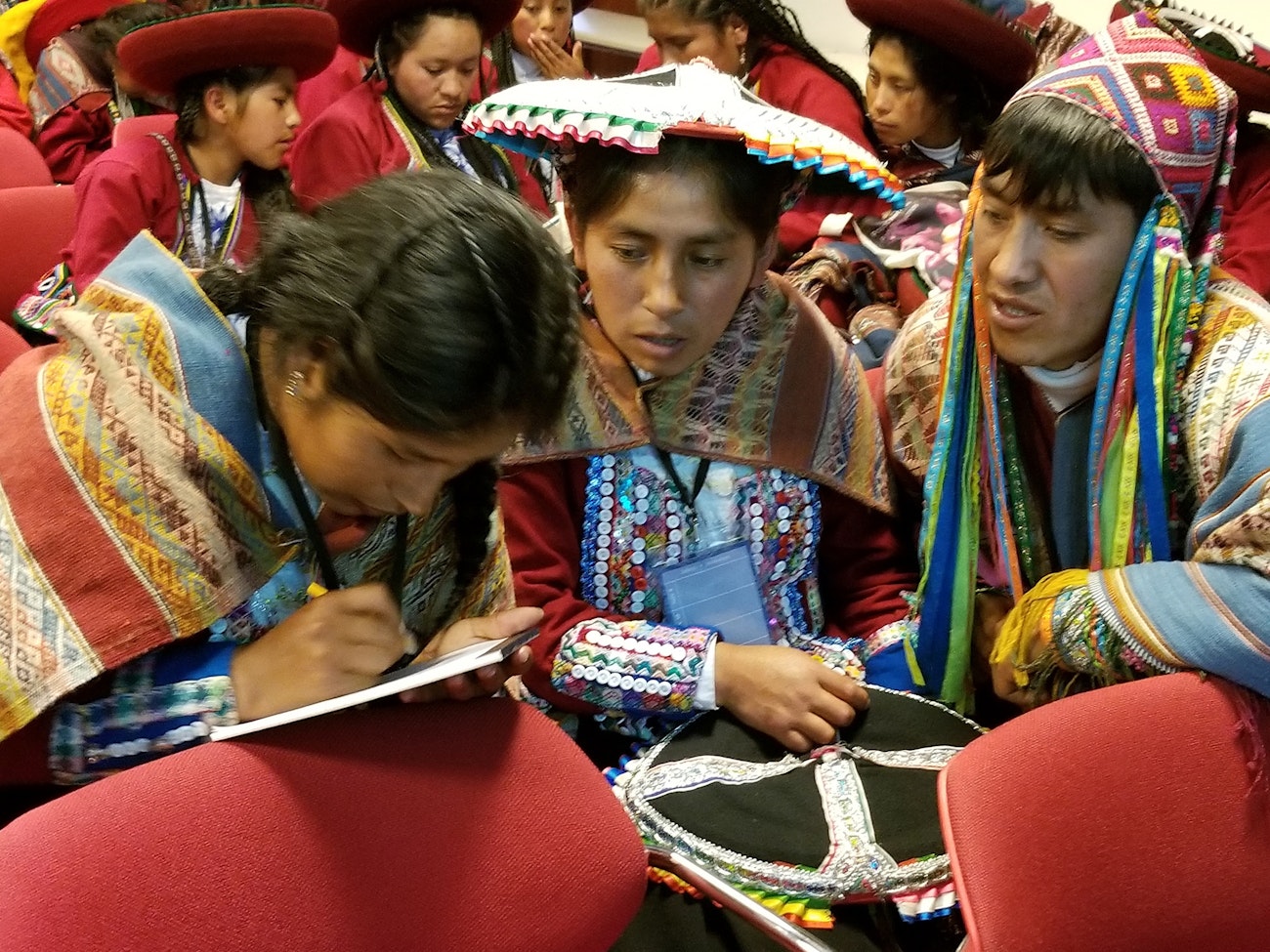

Children from Pitumarca work together crafting text for their book. They were attending Tinkuy 2017 in Cusco, a gathering of weavers of all ages from around the world. Photo by Marilyn Murphy

Children from Pitumarca work together crafting text for their book. They were attending Tinkuy 2017 in Cusco, a gathering of weavers of all ages from around the world. Photo by Marilyn Murphy

So who learned what? I hope that working on this project led some kids to have meaningful conversations with their elders and helped them feel even more fully integrated into a centuries-old lifestyle that’s abundantly worthy of preservation. For me, it was experiencing the remarkable energy and intelligent decision-making on the part of these young people, some of whom will never have more than an elementary education. It was observing their ability to work collectively in groups both large and small and to work toward consensus, as their people have always done.

Four young weavers from the remote village of Huacatinco display their best festive outfits, replete with lots of beads.

Four young weavers from the remote village of Huacatinco display their best festive outfits, replete with lots of beads.

One of the children who contributed to the book when she was 11 and 12 years old, Hilda Yesica Mamani Chura, is now 17 and has traveled far from her village of Accha Alta to study accounting and finance at Instituto Khipu in Cusco. Her hope is to be able to help her home village acquire financing to continue their traditional crafts, and she also hopes to go back to help teach younger children the skills at which she has become so adept. What has become of her copy of the book she worked so hard on? I have no idea. But I hope it helped cement her commitment to a life that will straddle the old and the new and all the challenges that will present.

Las Tradiciones Viven

(Traditions Live: The Next Generation of Weavers)

A PDF download of the whole book, including an English translation, can be found at andeantextilearts.org. An optional $10 donation is requested.

Las Tradiciones Viven

(Traditions Live: The Next Generation of Weavers)

A PDF download of the whole book, including an English translation, can be found at andeantextilearts.org. An optional $10 donation is requested.

Interested in other ways of learning craft? This article and others can be found in the Spring 2023 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Spring 2023. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Andean Textile Arts, andeantextilearts.org.

- Weave a Real Peace (WARP), weavearealpeace.org. WARP is a networking organization for people involved in indigenous textiles and their creation. Information on Hilda Yesica Mamani Chura was taken from a webinar presented by this organization.

Linda Ligon is a cofounder of Long Thread Media.