The onset of World War I (1914–1918) brought about a tremendous demand for handknitted socks and other garments for the troops, which in turn spurred on a nationwide knitting fervor in this country. As a result of widespread campaigns encouraging volunteer knitting, working men and women, young children, suffragists, and performing artists, among others, joined combatants’ family members to provide much-needed supplies to fighting soldiers and sailors.

Even before the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, volunteer organizations in the United States encouraged knitters to knit for British fighting troops who had begun fighting in 1914. The need for socks was especially acute. It has been said that an army’s strength depends on the health of its soldiers’ feet.

It was essential to have clean and dry socks to ward off disease, particularly in the trench warfare of World War I, where soldiers were crowded into muddy, wet, and narrow trenches. More than 74,000 Allied soldiers were afflicted by trench foot: a serious condition that could lead to gangrene and amputation. Notably, the British War Office allocated soldiers only three pairs of socks every six months. Knitters in the United States helped close the gap between the number of socks British soldiers required and the number of socks the British Army supplied.

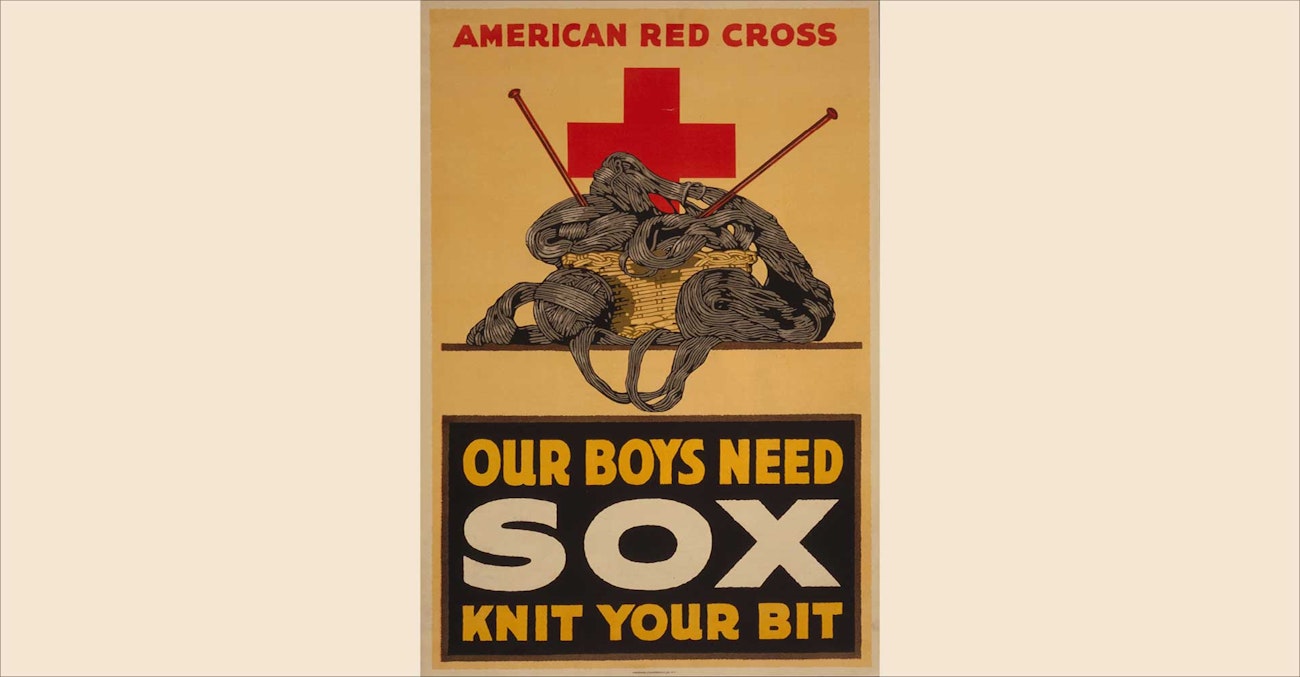

American Red Cross poster promoting sock knitting during World War I. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Divisions

The American Red Cross

The American Red Cross was the preeminent organizer of volunteer knitting activities in the United States during World War I. The Red Cross developed knitting pattern books for military garments and accessories, acquired and distributed wool for knitters, and then collected and helped the military hand out items completed by volunteer knitters.

With the intention of getting as many people to knit as possible, it also provided knitting instruction to novice knitters (including men and children), as well as places for new and experienced knitters to gather and knit. In 1917, the Red Cross founded a new organization, the American Junior Red Cross, and a focus of that group was to encourage school children to knit and to engage in other activities in support of the fighting troops.

Because the Red Cross volunteer knitters followed the specifications set forth in the Red Cross’s knitting pattern books, there was considerable uniformity in the construction and sizing of the items they produced. At a time when the sizing of knitting needles was not standardized, the Red Cross even specified the diameter of the needles, called Red Cross Needles No. 1, 2, and 3, that should be used to knit particular patterns. Red Cross knitting patterns were straightforward and could be followed by knitters of varying abilities.

The American Red Cross grew exponentially during the United States’ involvement in World War I. On May 1, 1917, shortly after the United States entered the war, the American Red Cross had 562 chapters with approximately 486,000 members, and by February 28, 1919, the American Red Cross had 3,724 chapters with approximately 20 million adult members and 11 million junior members. Among its membership were men, women, and children from all walks of life, including 5,000 Native American adults and 30,000 Native American students, many of whom were enlisted by the Red Cross as volunteer knitters.

The output of the Red Cross’s volunteer knitters was prodigious. In a 1919 report on its work during World War I, the Red Cross noted that it had provided the following number of knitted items to soldiers and sailors in the United States alone in the 20-month period ending February 28, 1919: 7,142 afghans; 985,841 helmets (or balaclavas); 901,830 mufflers; 3,592,126 pairs of socks; 4,208,935 sweaters; 1,199,420 wristlets; and 3,801 miscellaneous items. The same report states that comfort supplies, “particularly the knitted sweaters, socks, etc., made by chapter women in America,” were issued “by the million” to troops fighting in France (see note 1).

Attendees at the Knitting Bee included Civil War veteran I. E. Seelye, a knitter, pictured here with two British soldiers. Photo courtesy of the National Archives Gallery from the American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs

The Comforts Committee of the Navy League

In March 1917, the Women’s Section of the Navy League formed the Comforts Committee of the Navy League to supply sailors with knitted clothing. By August 1917, the Comforts Committee had enlisted one hundred thousand volunteers who completed more than seventy thousand sets of knitted garments including vests, mufflers, wristlets, and helmets. These items were made from either navy blue or oxford grey wool.

From July 30 to August 1, 1918, the Comforts Committee sponsored a three-day Knitting Bee in New York City’s Central Park. According to the New York Times, the chairwoman of the Comforts Committee quipped that if the weather was pleasant on the third day of the Knitting Bee (inclement weather apparently plagued the first two days of the event), “the knitters would be out in such numbers that the click of the needles would be heard in Berlin (see note 2).”

The Knitting Bee included at least 50 contests for different classes of knitting men, women, and children. Ethel Rizzo of New York City “took the first prize in the speed contest, knitting a square of twenty-one rows, twenty-eight stitches each, with five needles in eight minutes (see note 3).” Rizzo also was awarded a prize for knitting a sweater on three needles in one afternoon. The Knitting Bee raised $4,000 and during the event, knitters completed 50 sweaters, 48 mufflers, 224 pairs of socks, and 40 helmets, which all became the Committee’s property.

Ironically, the Comforts Committee itself could not forward the items completed at the Knitting Bee to Navy sailors because on August 17, 1917, the Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels (1862–1948) had issued an order prohibiting the Navy League from giving any goods to Navy personnel. According to the design and textile historian Rebecca Keyel, this order resulted from a “contentious relationship” between Daniels and the president of the Navy League and their dispute regarding the identification of the perpetrators of an explosion at a Navy yard.

Although many Comforts Committee volunteers switched to knitting for the Red Cross after Daniels issued his order, the Comforts Committee did not stop its knitting campaign. Rather than have the Comforts Committee forward donated items to the Navy, the Comforts Committee’s honorary chairman sent donated knitted items to Navy sailors in her personal capacity.

Suffragists

In a recent PieceWork article, “Another Noble Cause: Suffragist Knitters of World War I,” the textile and knitting historian Susan Strawn noted that, during World War I, The Women Citizen, the official publication of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, praised knitting as patriotic and encouraged suffragists to knit. Suffragists from throughout the United States provided The Women Citizen with reports of their knitting productivity.

Suffragists from the 27t h Assembly District of the Suffrage Party in New York City—the Knitting 27 th— knitted 712 sets of the garments prescribed by the Comforts Committee, one set for each of the 712 sailors stationed on the USS Missouri, a Maine class battleship that served as a training vessel in the Chesapeake Bay area during World War I. According to Strawn, the suffragists’ knitting represented “73,491,216 stitches, or 40,828 hours of knitting.” Strawn further notes that these suffragists knitted with donated wool, or wool that had been purchased with cash donations, resulting in “an estimated savings to the nation of $6 million to $7.5 million (see note 4).”

Knitting by Universal Motion Picture Company employees, 1917, published by the New York Herald. Photo courtesy of the National Archives Gallery from the American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs

Knitting in the Workplace

The Stage Women’s War Relief, which was organized in New York City at the beginning of World War I to coordinate volunteer efforts by women in the theater, sponsored its own knitting campaign headed by the actress Mary Boland (1882–1965), who also entertained troops in France during the war.

According to the National Archives, the Universal Motion Picture Company in New York City was one of the first business organizations in the United States to encourage its male employees to knit during their lunch hour, with female stenographers acting as the knitting instructors. Female office workers also knitted at the office while on breaks. Indeed, knitting became such an accepted part of the professional workplace that even grand jurors were found knitting.

In Knitting America, author Susan Strawn recounts the story of 800 workers (who included some men) in the Butterick Building in New York City who learned to knit in two one-half hour lessons and then, in six weeks, turned out 792 garments—a sweater, gloves, and two pairs of socks each for the 198 sailors stationed on two Navy destroyers. Thereafter, Butterick appealed to its readers to join with its employees in knitting a total of 7,032 handknitted garments for the crew of 879 sailors stationed on the Navy’s largest battleship, the USS Nevada.

Members of the fire department of Cincinnati, Ohio, making sweaters, socks, and mufflers for soldiers in France. Photo shows women members of the American Red Cross teaching firemen the art of knitting for the soldiers. Photo courtesy of the National Archives from the American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs

Knitting by Convalescing Combatants and Interned Prisoners of War

Soldiers and sailors themselves also became knitters. Wounded veterans knitted in hospitals as a rehabilitative measure. The Lafayette House, a New York City convalescent home for wounded veterans, offered knitting instruction. Allied and enemy prisoners of war also knitted, both to make clothing for themselves and to pass the time. And, even before the United States entered the war, Russian, Austrian, and German aliens, who had been detained at Ellis Island after the war started in Europe, were provided with materials to knit articles for the American Red Cross.

According to the National WWI Museum and Memorial, between the United States’ entry into the war on April 6, 1917, and the end of the war on November 11, 1918, volunteer knitters in the United States dedicated two million hours (the equivalent of 230 years of labor) and used 45 million pounds of wool in knitting for the troops. Volunteer knitters are reported to have donated 22–23 million garments for soldiers and sailors stationed domestically and overseas. Volunteer knitting allowed civilians to demonstrate their patriotism as they made meaningful contributions to their country’s war effort by knitting critically needed supplies.

Interested in learning about moonlighting makers? This article and others can be found in the Spring 2024 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Spring 2024. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Notes

- American Red Cross, The Work of the American Red Cross During the War: A Statement of Finances and Accomplishments for the Period July 1, 1917, to February 28, 1919 (Washington, DC, 1919).

- “Knitting Bee Nets $4,000,” New York Times (August 2, 1918), 7.

- “Knitting Bee Offers 50 Prizes,” New York Times (July 14, 1918), 19.

- Susan Strawn, “American Women and Wartime Hand Knitting, 1750–1950,” in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750–1950, eds. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (London and New York, 2009), 245–59.

Resources

- Burgess, Anika. “The Wool Brigades of World War I: When Knitting Was a Patriotic Duty.” Atlas Obscura, July 26, 2017. atlasobscura.com /articles/when-knitting-was-a-patriotic-duty-wwi-homefront-wool-brigades.

- Keyel, Rebecca J. “‘Knit Your Bit’: The American Red Cross Knitting Program.” Center for Knit and Crochet, April 13, 2019. centerforknitandcrochet.org/knit-your-bit-the-american-red-cross-knitting-program.

- ———. “The Navy League.” Center for Knit and Crochet, August 28, 2019. centerforknitandcrochet.org/the-navy-league.

- Korda, Holly. The Knitting Brigades of World War I: Volunteers for Victory in America and Abroad. Self-published: New Enterprise, 2019.

- Strawn, Susan. “Another Noble Cause: Suffragist Knitters of World War I.” PieceWork Summer 2023: 45–49, pieceworkmagazine.com/another-noble-cause.

- ———. Knitting America: A Glorious Heritage from Warm Socks to High Art. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2007.

Mimi Seyferth, a lawyer and knitter, lives outside Washington, DC. In conducting research for this article, she was delighted to discover a contemporary children’s book—Knit Your Bit: A World War I Story by Deborah Hopkinson, illustrated by Steven Guarnaccia (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013)—about a boy who learns to knit to participate in the Knitting Bee in Central Park and gives the one sock he is able to complete to a soldier who had lost a leg in combat.