Sol (“sun”) laces—so-called because the design radiates from the center—originally were made directly on a background fabric. Circles of running or backstitch were made, and threads were run under these stitches and across the circle like the spokes of a wheel. This made a sort of loom to support circular weaving and knotting together of the spokes, which formed the lace design. Fabric at the back was then cut away and the raw edges overcast or finished in a buttonhole stitch.

Clockwise from top left: a sun lace constructor, a wooden sun lace frame, and a pillow sun lace frame. All late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Constructor courtesy of the author; frames courtesy of the Historic Costume and Textiles Collection, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Clockwise from top left: a sun lace constructor, a wooden sun lace frame, and a pillow sun lace frame. All late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Constructor courtesy of the author; frames courtesy of the Historic Costume and Textiles Collection, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

At some point, the lace began to be made separately from the background fabric on a small pillow or other circular frame. A circle of pins formed a frame or loom across which the warp threads were strung. Some lace makers used a paper pattern to guide the spacing of the pins and the weaving and knotting of the threads.

Sun laces first appear in Spanish portraits painted during the sixteenth century; the style remained popular in Spain for the next 150 years. Also called ruedas (“wheels”), these laces may well have been brought to Spain, perhaps from Italy or the Netherlands, either by trade or seizure. No documentation, such as payments for making the lace, inventories, or bequests, has been found for these laces in Spain.

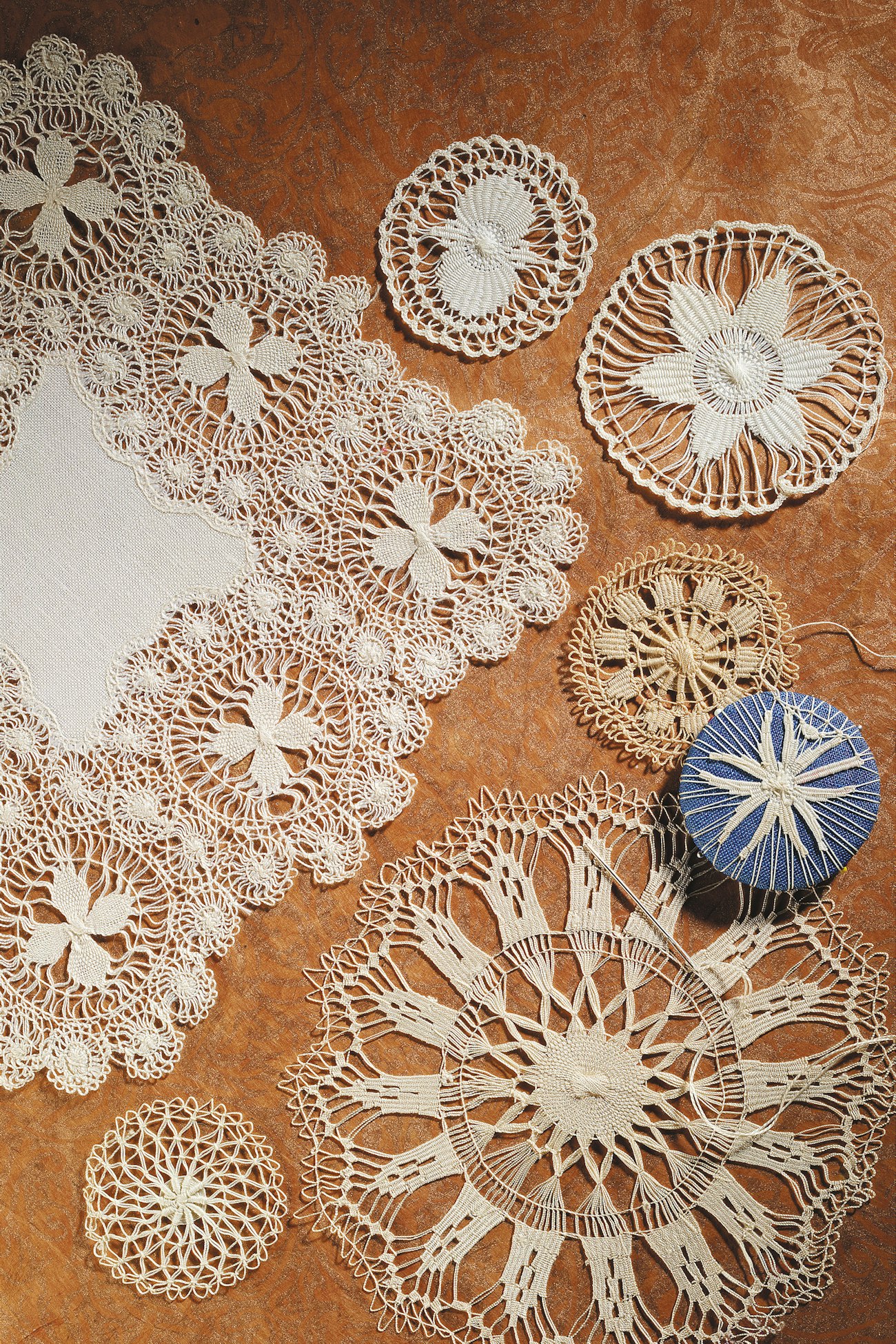

Examples of sun laces. Late nineteenth or early twentieth century. From the Historic Costume and Textiles Collection, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Photograph by Joe Coca

We do know, however, that during the sixteenth century the laces traveled to Spanish colonies in South America. A woman who accompanied the conquistadors is said to have brought the technique to Brazil, and the laces also appeared in Mexico and Bolivia. In Paraguay, a variant known as nanduti (an indigenous word for “web”) developed in the eighteenth century. Perhaps the Jesuits introduced it to help indigenous populations who had been deprived of their land earn a livelihood by making church vestments and linens. Nanduti, like other sun laces, is worked on a frame; unlike the other laces, however, that are made primarily from cotton thread, nanduti is typically made of silk.

Another variation of sun lace, called Teneriffe (or Tenerife), is still made for tourists on Tenerife, the largest of the Canary Islands, which lie off the coast of North Africa and are a province of Spain. The people of Tenerife, however, call it Brazilian lace, which suggests that the technique came to the island from South America. Teneriffe lace is also worked on a frame and usually made with cotton thread.

In eighteenth-century Dorset, England, the making of cross-wheel buttons, a kind of sun lace worked over wire covered with buttonhole stitch or crochet, was a cottage industry that provided considerable income to Dorset women.

During the late nineteenth century, a tool for making sun laces was devised. Called a constructor, it resembled a spool topped with a metal cap, whose toothed edges held the warp threads. The center of the cap could be raised slightly to exert tension on the threads while working the design and lowered to lift off the finished lace. Lace constructors are no longer being made.

Sun laces are as appealing today as they were five centuries ago. I encourage you to try your hand at this relatively easy-to-master and absolutely rewarding technique.

Interested in trying your hand at these round laces? This article and a companion project can be found in the January/February 2001 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including January/February 2001. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. Mineola, New York: Dover, 1999.

- Kliot, Jules, and Kaethe Kliot, eds. Teneriffe Lace. Berkeley, California: Lacis, 1986.

Margaret Horton learned many kinds of stitching techniques from her mother in Nottingham, England.

Originally published October 26, 2020; updated March 17, 2025.