In 1753, 13-year-old Mary Wright made a journey that would have been unusual for any young woman living in colonial Connecticut: she traveled 100 miles for the sake of her education. There were no schools for girls near her home in Middletown, nor opportunities for “improvement.” But Mary—or Molly, as she was called then—was the only child of Hannah and Joseph Wright,and her father was the owner of a brickyard that had made him one of the most prosperous men in Middletown. From birth, she had never wanted for anything.

Perhaps if Molly had had a brother, he would have been the one to have been sent to school instead. Perhaps her parents viewed her education as a symbol of their own rising status in their community, or perhaps another family member or friend suggested it. Or perhaps it was Molly herself who asked to go away to school, to catch a glimpse of a world beyond rural Middletown.

It’s likely that her father accompanied her, traveling by ship down the Connecticut River, and then along the New England coast to Newport, Rhode Island. It is believed that he enrolled her in the popular boarding school owned by Sarah Haggar Wheaten Osborn. Mrs. Osborn was a deeply religious woman and a spiritual leader in her community, as well as a reassuringly trustworthy teacher for the Wrights’ daughter. Mrs. Osborn’s school had none of the more frivolous classes—French, dancing, music—that would become common later in the century. Instead, her curriculum was more straightforward, advertised as “Reading, Writing, Plain Work, Embroidery, Tent Stitch, Samplers &c, on reasonable terms.”

The emphasis on needlework over other subjects shows its importance in colonial New England. Needlework skills of all kinds were marks of virtuous accomplishment, gentility, and modest industry—all highly prized qualities for girls from prosperous families. To become exemplary wives and mothers, these girls were expected to be not only ornamental themselves, but also able to produce ornamental objects for their homes and families.

Schoolgirl Stitching in Newport

For young Molly, Newport itself must have been an education. With a population of around 10,000, Newport was one of the largest cities in the Colonies,a cosmopolitan port with a much more diverse population than she ever would have encountered in Middletown. Walking through the town with her teachers, Molly would have passed people not only from Europe, but also from Africa and Asia. The salty ocean air would have mixed with the smoke of hundreds of fireplaces, the smells of open-air markets and cattle for sale, and the fermenting tang from the 22 distilleries that created the rum that was essential to Newport’s trading. Ships from around the world docked in the harbor, and the shops rivaled those in London and Paris for the wealth of their goods.

Even Molly’s needlework reflected Newport’s international trade. The fine linen used for her embroidery could have come from Ireland. Her steel needles could have come from Redditch or Birmingham in England. The wool threads for the best crewelwork were spun from British sheep, while silk was imported from China or India by way of England.

Embroidered picture, Mary Wright (1740–1829), circa 1754, Newport, Rhode Island, linen embroidered with wool and silk thread, 7 5/8 x 7 5/8 in. (19.4 x 19.4 cm), Rogers Fund, 1946, Accession Number 46.15. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Embroidered picture, Mary Wright (1740–1829), circa 1754, Newport, Rhode Island, linen embroidered with wool and silk thread, 7 5/8 x 7 5/8 in. (19.4 x 19.4 cm), Rogers Fund, 1946, Accession Number 46.15. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Even the colors of the wool and silk often relied on imported dyes: cochineal from Mexico produced reds, indigo from India made blues and violets, turmeric from southeast Asia created the best golden yellows. When Mrs. Osborn drew designs for her students to work, they were copied from prints imported from London, and they featured artists from England and the Netherlands.

A number of Molly’s needlework pieces survive from her time in Newport, carefully preserved by her descendants through the centuries. It’s clear from these pieces that Molly thrived in her new school. Soon she was stitching elaborate tent-stitch pictures of fashionable ladies in bucolic settings, as well as chair seats featuring swirling flowers, and a pocketbook in delicate queen’s stitch. Often, she included her own name or initials, proudly signing her work for posterity. The detail and care of these pieces prove that Molly was stitching not just to please her teachers and parents, but also for her own pleasure. For a young teenager, she was remarkably accomplished.

Flat, folding pocketbooks carried paper money, bills, and important letters, much like wallets today, and they were popular small projects for needleworkers. While in Newport, Molly made one for her father, worked in wool tent stitch. The design features a tree of life, blossominginto flowers: a lovely symbolism for a father and daughter. Molly included his name, plus her own initials, further linking them together.

Today the pocketbook is worn and so threadbarethat the faded inked design beneath the stitches shows through, a victim of time and moths. But it’s also easy to imagine her father causing the wear, repeatedly pulling the pocketbook from his coat pocket to show off his daughter’s accomplishments at her boarding school, much as modern parents wear T-shirts from their children’s colleges, eager for any excuse to do a bit of boasting.

Mrs. Richard Alsop

It’s not known how long Molly studied with Mrs.Osborn in Newport. Soon after her twentieth birthday, in 1760, Molly—now known as Mary—married 34-year-old Richard Alsop in Middletown. The Alsops were a wealthy and well-connected New York family. Richard was already a prosperous merchant, having begun his career in the counting houses of New York merchant Philip Livingston—the Colonial equivalent to a top business school. By the time he wed Mary, he had branched out on his own, as a merchant and shipowner in the lucrative West Indies trade, with cargo that ranged from horses to coffee, molasses, rum, and steel. He also served as a representative to the state’s General Assembly and participated in local town commissions.

Mary’s responsibilities were focused on her ever-growing family. Like many eighteenth-century women, she was often either pregnant or tending to a young infant. Over the course of her marriage, she gave birth approximately every 18 months, with eight of her ten children surviving beyond childhood.

The large gambrel-roofed house that Richard’s success provided would have been her responsibility, and she would have had to entertain her husband’s guests and business associates, as well as look after her children. Yet as a wealthy woman, Mary would not have done all this alone. Records show that she had several servants, some of whom were enslaved. Her aging parents still lived nearby, and their welfare also would have been her responsibility as a dutiful daughter.

For Mary, her family’s wealth meant that she could afford imported materials and had time to create decorative needlework. She embroidered practical items, such as chair slips for mahogany chairs and fire screens that were listed in family inventories, and frivolous items such as tiny, spangled flowers in metallic thread on silk for her gowns. Unlike many gentlewomen who ceased handiwork once they were wives and mothers, Mary’s dedication to stitching seemed only to grow and become more refined.

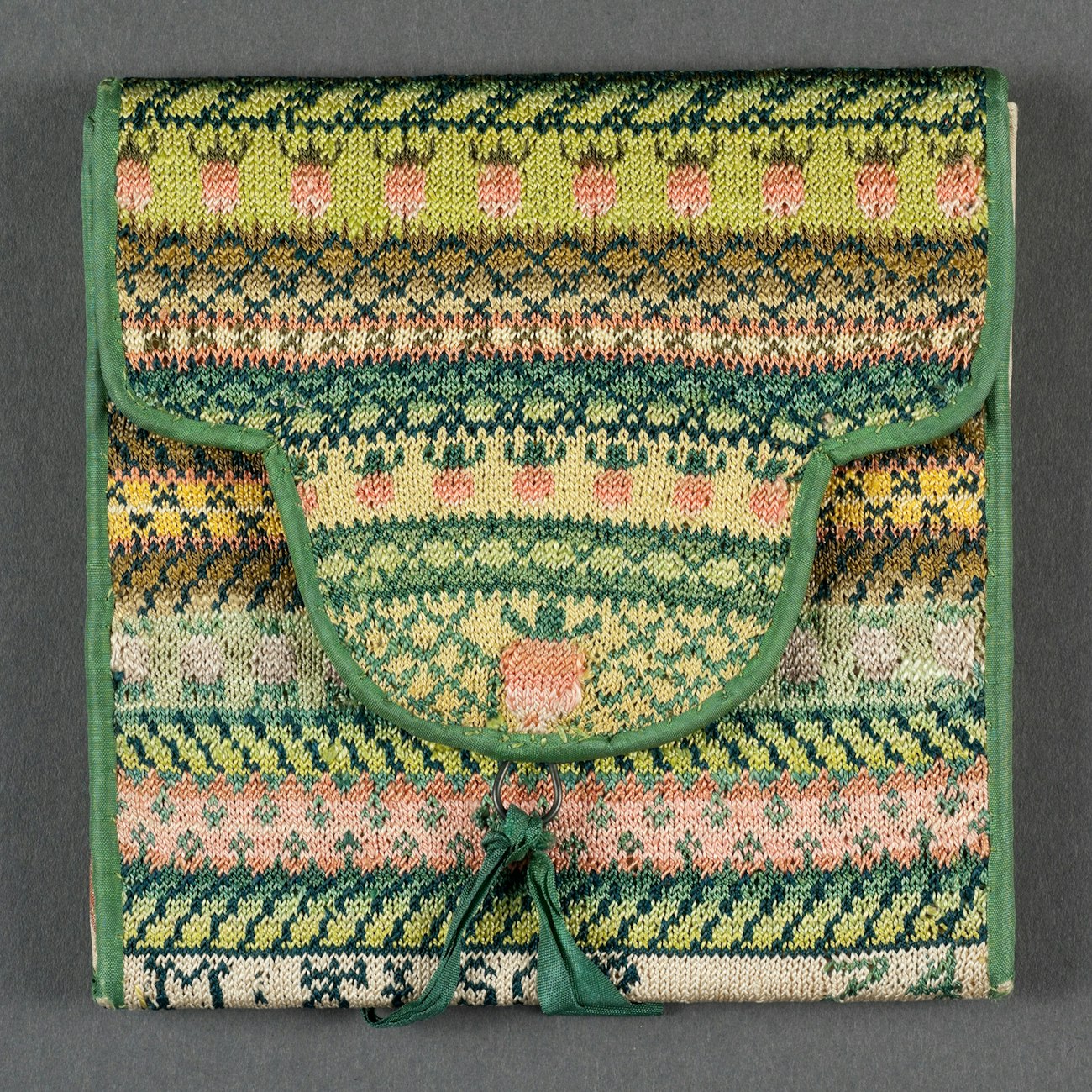

Pocketbook made by Mary Wright Alsop. Middletown, Connecticut, 1814. Silk, Linen, Canvas, Cardboard, 1955.0003.003. Gift of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

Pocketbook made by Mary Wright Alsop. Middletown, Connecticut, 1814. Silk, Linen, Canvas, Cardboard, 1955.0003.003. Gift of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

The surviving pocketbooks she created for her husband were worked in tent stitch, using both silk and wool threads, over linen at an astonishing 38 threads per inch. In one example, the overlapping flap is an elegantly curving trilobed design that echoes the same graceful arches in Georgian architecture and furnishings. Richard’s name is worked along the edge, and Mary added her own initials beside it. The edges are bound with silk, and the bright silk damask lining, reinforced with cardboard, could have been a remnant of one of Mary’s own gowns.

By the early 1770s, however, even the well-ordered lives of the Alsops had begun to feel unsteady. The first rumblings of what would become the American Revolution were already being felt in Middletown, and as a shipowner and merchant, Richard’s trade was threatened both by restrictive Acts of Parliament and the local boycotts that followed.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, in April 1776, shocked New England and drew the Colonies inexorably toward war with Great Britain. But a different tragedy came to Mary Alsop that same month: without warning, Richard died, leaving her a widow with eight children, the oldest only 15, the youngest a 2-month-old baby.

He also left her as executor of his large and complicated estate. Valued at nearly £35,000, his assets included ships, cargo, and business holdings; numerous parcels of real estate in Connecticut and Jamaica; and the debts and loans that were part of eighteenth-century business. It wasn’t typical for a husband to trust his widow with this responsibility, but in most cases, the women had brothers or fathers to assist them. But Mary’s father had died the year before, she had no brothers, and she never remarried. Instead, she herself took full responsibility, successfully guiding her late husband’s affairs until the estate was finally settled, 14 years later.

It was a formidable task. With many assets but little cash, Mary was forced to lead a financially careful life, balancing risk with necessity. Yet throughout the turbulent years of the Revolution, she successfully maintained Richard’s mercantile business, consolidated his real estate holdings, and collected debts until the estate was finally clear and her income was certain—and all the while raising her children.

Understandably, there are few examples of her needlework from this period. But there is a remarkable portrait of Mary by Ralph Earl that dates to 1792, when she was 52. She sits at the window of what is believed to be her parents’ farmhouse, where she’d been born. Her expression is determined, if a little weary; she has, after all, been through a great deal. Her extravagant cap is the literal height of Federalist fashion, a bit of frivolity that she’s permitted herself. Worn over a green silk gown, the sheer linen or silk of her apron and kerchief display are decorated with whitework or tambour embroidery, and it’s not unreasonable to assume that it’s Mary’s needlework again on display. One hand rests on a silver snuffbox, while the other holds a handkerchief. If taking snuff (common among both men and women) was Mary’s small vice, then she had earned it.

Another, later, collection of Mary’s handwork also survives, preserved now in the Winterthur museum. By the early nineteenth century, Mary’s children were grown, with five married into other prominent families and two daughters still living with her. Fashions had changed since she’d made the tent-stitch pocketbooks, and the newer men’s and women’s clothing no longer had deep pockets to accommodate bulky pocketbooks. At this time, when Mary wished to make small, useful gifts for her children and grandchildren, she turned to knitting purses.

These little drawstring bags were knit with silk thread on steel needles that would probably be a modern size 000 or smaller, which produced a minute gauge of around 20 to 22 stitches to the inch. Mary chose vibrant colors, full of contrast, and the purses are lined with equally colorful silk cloth, taffetas and ikats and damasks that had likely been tucked in Mary’s scrap basket for the decades since those fabrics were fashionable.

Also borrowed from an earlier time are the knitted designs themselves. The neat rows of stylized flowers, strawberries, and geometric elements echo the borders of cross-stitched samplers popular in Mary’s youth, while the zigzag motifs seem directly drawn from eighteenth-century flame-stitch embroidery. Clearly Mary took embroidery designs that she remembered and still found pleasing, and she translated them to knitting. She also treated the knitted pieces like woven fabric. Instead of knitting the purses seamlessly on multiple needles like stockings, she knit them as flat rectangles and seamed them into shape.

Knitted purse, early nineteenth century, inscribed L.W. Alsop. Purse (USA); silk, metal; H x W: 11 x 8 cm (4 5/16 x 3 1/8 in.);1960-35-3, Courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Museum

Knitted purse, early nineteenth century, inscribed L.W. Alsop. Purse (USA); silk, metal; H x W: 11 x 8 cm (4 5/16 x 3 1/8 in.);1960-35-3, Courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Museum

Also reminiscent of the earlier pocketbooks is the way that each has the recipient’s name knitted into the border, as well as Mary’s own initials. In some cases, the date also appears. While knitted, one example returns to the flat envelope style of the old pocketbooks, complete with the trilobed flap and a stiffened cardboard lining. Made for her daughter Fanny, the design featured not only Fanny’s name, but also the date (1814) and “M. Alsop 74”—proudly featuring her own name and age, too.

The purses are in such excellent condition that it’s possible they weren’t used by the recipients, but instead kept as mementos. Like grandmothers of every generation, Mary wasn’t above accompanying her gifts with a bit of guilt, too. “I send you a Purse which I knit for you sometime[sic] ago, hoping to have the satisfaction of giving it to you myself,” she wrote to a grandson. “Receive it as a small testimony of my affection.” One hopes that grandson immediately hurried over to thank her in person.

In 1815, Mary knitted a purse for a newborn granddaughter, named Mary Wright Alsop in her honor. The little note that Mary slipped inside the purseremains with it still: “This is for/Mary Wright Alsop/to buy a ring, or/any other article in/Memory of her affect./Grand Mother Mary Alsop/Octr 1815.” What better way for Mary to be remembered?

The author would like to honor the memory of two legendary scholars—Linda Eaton (1955–2021) and Glee Fox Krueger (1931– 2018)—for first introducing her to Mary Wright Alsop and her needlework. In addition, she would also like to thank Elizabeth Palms, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, and Neal Hurst, Colonial Williamsburg, for their assistance with this article.

Interested in reading more about the repetition of needlework? This article and others can be found in the Summer 2024 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Summer 2024. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Susan Holloway Scott is the nationally best-selling author of 55 historical novels. She lives with her family and a mess of cats near Philadelphia. For more information about her books and the fascinating people, places, and things she discovers through her research, check out her website and blog, susanhollowayscott.com.