A knitting magazine advising readers to get out and vote, a plea for world peace in the pages of a quilting magazine, a review of child welfare amid embroidery patterns. Incongruous as these scenarios may appear today, an American woman living a century ago would not have been surprised to find such political messages woven into the text of the current issue of the needle-arts magazine in her workbasket.

Confined to the home by both cultural expectations and necessity, most American women of the early twentieth century were excluded from politics. But even before the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted them the right to vote in August 1920, some nevertheless managed to monitor world affairs, voice their opinions, and exhort fellow housewives to social and political action—through the pages of such seemingly innocuous but widely read magazines as Needlecraft and The Modern Priscilla. (The general interest magazines of the period also explored social and political aspects of American life. Sarah Abigail Leavitt, in her book From Catharine Beecher to Martha Stewart: A Cultural History of Domestic Advice [Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2002], suggests that according to the “Big Six” magazines of that period—The Delineator, Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Pictorial Review, and Women’s Home Companion—reform in the home could lead to reform in society.) Before television, before the internet, before the widespread use of radio, when even telephone service was often unavailable or unpredictable, these needlework publications at their peaks reached a total of more than one million subscribers.

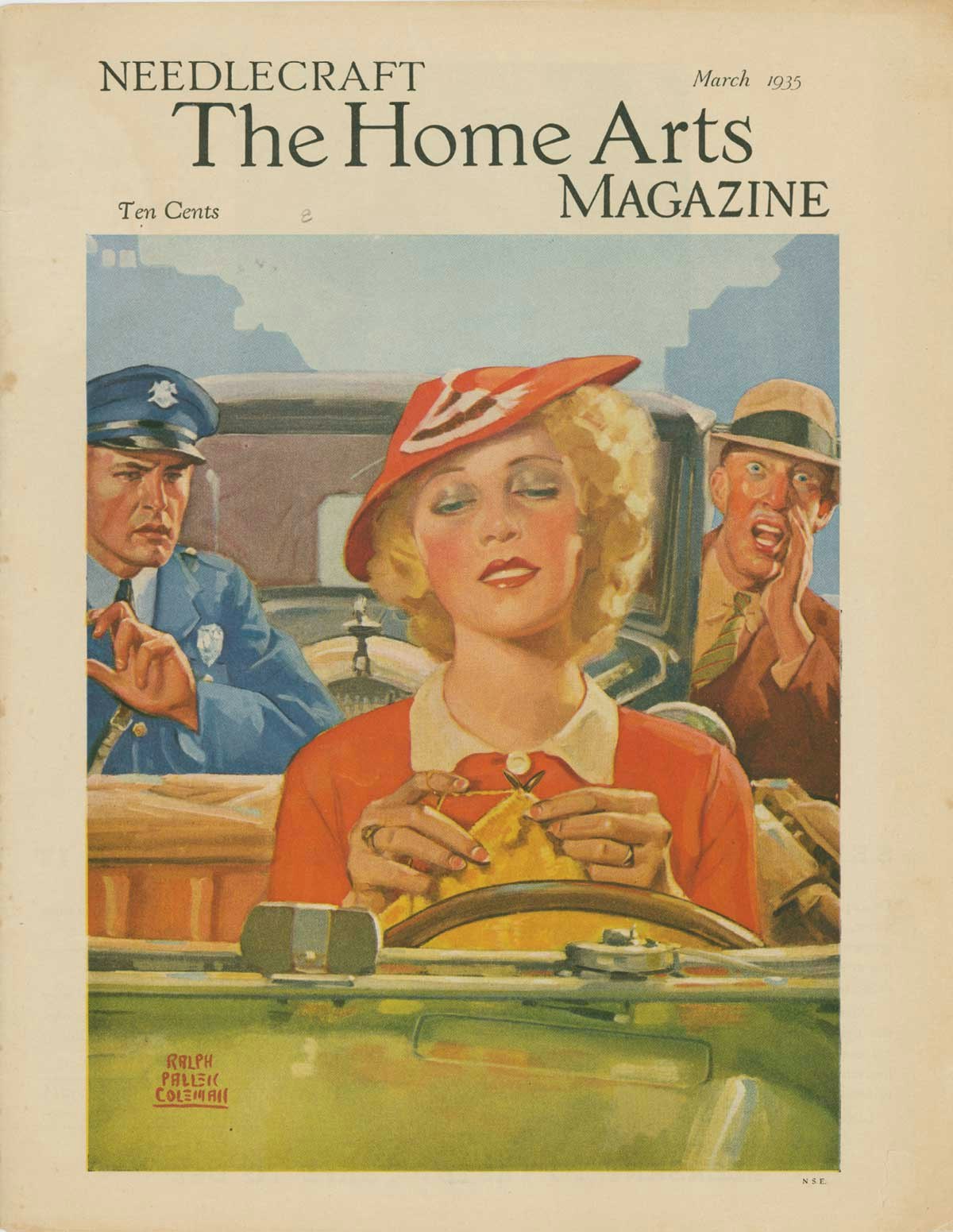

Cover of the March 1935 issue of Needlecraft—The Home Arts Magazine. All magazines from the collection of the author.

The earliest issues of Needlecraft, founded in 1909, focused on family comfort and household necessity, but in the January 1913 issue, the topic of “pin money” became a topic of continued attention. The editorial page began to offer advice on earning opportunities for women, with occasional comments on their right to independent means:

[T]he wife, mother, or sister, who cares for home and children, doing her duty faithfully, is entitled to a portion, and a generous one, of the family income, but the fact remains that she does not always or, I may say, often, receive it. . . . [T]he average woman goes without the dime rather than ask for it.

ADVERTISEMENT

The editorials on this theme encouraged women to develop their needlework skills for the production of income, suggesting ways to find or create self-employment for themselves or to cultivate community collaboratives for selling to the outside world.

Auto Knitter Hosiery Company advertisement in the February 1924 issue of Needlecraft Magazine.

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson declared the United States’ neutrality, but American women’s magazines nevertheless encouraged relief efforts for European soldiers:. “Everybody is knitting[,] . . . and the helmets and socks and mufflers are all going as fast as steam can carry them to the battlefields of the old world. . . .” declared Margaret Barton Manning, the editor of Needlecraft, in January 1915. She reminded readers that civilians abroad also needed help as indeed did families here at home:

[T]he question forces itself upon the thoughtful mind: why should all the relief go abroad? . . . It is true that Europe is suffering because of the dreadful and unnecessary conflict that has been forced upon the people there; our hearts ache for them, more than all for the helpless, innocent children upon whose young lives the blight of war has fallen, and for the mothers who must see these little ones cold and hungry and homeless, and are powerless. . . .

There are children in our big cities, doubtless in country towns as well, to whom the holidays will bring no brightness unless our relief-works think to divide up a little. The European war has entailed much suffering on our own country. There are fathers out of work, mothers hollowed-eyed, and anxious, children poorly clothed and fed. . . . There is plenty of opportunity for relief-work right at home. Let your plans include America as well as Europe. The war of competition—of striving, one man or woman against another, for the chance to labor, is scarcely less cruel than that other war which we so deplore. And both are needless. In both, too, the children are chief sufferers. . . .

Let us lend a hand in aid of suffering humanity abroad—but let us not forget the claims of our brothers and sisters at home.

Following the armistice, as the world was beginning to recuperate from war’s destruction and American soldiers were returning home from the battlefields of Europe, Needlecraft again challenged readers to help (February 1919):

Among the war-stricken people of those devastated lands over which the tides of battle erstwhile ebbed and flowed the need was never more great than now. Clothing of every sort is wanted—sorely wanted. Go to the Red Cross chapter nearest you and ask what you can do. . . . And while we are doing our bit and our best for the little ones, the needy ones in other lands—let us not forget those of our own. There are opportunities to “lend a hand” all along life’s way.

This same issue published a lengthy inventory of ways in which readers might supplement government assistance to returning veterans by offering cheerful support in their own homes and communities. A subsequent issue described the efficacy of knitting and needlework training for disabled veterans unable to return to their former professions.

Cover of the September 1935 issue of Home Arts Needlecraft magazine.

The Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, had been enacted in January 1920, seven months before women achieved the right to vote. But although they had no legal rights regarding their persons, their children, their property, or their finances, women had fought hard for prohibition as a way to protect themselves and their children from their husbands’ alcohol-induced physical and financial abuse and neglect. Once women had achieved the right to vote, however, Needlecraft and The Modern Priscilla exhorted them to use it. When the subject of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment and ending prohibition arose, The Modern Priscilla (January 1924) reminded its readers of their responsibility to work for the best interests of “the family, the community, the nation.” In a passionate, front-page appeal entitled “Liquor,” the editor urged readers to apply the marvelous power they now possessed:

If liquor is not a good thing for your family, it’s not a good thing for any family. If it does not benefit your community, it will not benefit any community. If it does not serve the best interests of the family or the community, it cannot possibly serve the best interests of the nation. . . .

The women of this country can wield a tremendous influence at the polls if they will, and the liquor question still offers an opportunity for them to show the world that their influence is for progress and righteousness. As a voter, do not fail to do your part.

Editorial in the January 1924 issue of The Modern Priscilla magazine.

Just over a decade later, Hitler’s Germany was beginning to militarize, and diplomats were struggling to avoid another conflict in Europe. In its May 1936 editorial, the recently renamed Home Arts—Needlecraft, again spoke up:

We do not want to send our boys to foreign wars and it has been satisfactorily demonstrated to us that profits are only temporary. In the long run they are just non-existent. There are no dividends on war. There is only pay, pay, pay. . . .

We know that peace can only follow world understanding and good will. Good will just does not come from a robbed victim or a plundered nation. Good will can and will come when the common people of all nations have the opportunity to work in gainful occupation and pursue peaceful, abundant lives at home. Before such a millennium can come, the natural resources of the world must be available on fair terms to all nations. . . .

War will not accomplish this. Nor will it ever be accomplished by bullying, no matter in how much state we dress it up. . . .

We shall be challenged. We shall be challenged by the short sighted, by the ignorant, by the greedy and the stupid. We shall be challenged by smart men who know what they are after and have been accustomed to getting what they want. And we must answer every challenge. . . .

ADVERTISEMENT

In the May 1931 Needlecraft, the president of the Maternity Center Association asked: “Will you help make this Mother’s Day mark the beginning of an attempt to obtain adequate maternity care for every mother in the United States? Perhaps not all realize that, as a nation, we have the highest maternal death rate of any civilized country. . . . Let this Mother’s Day . . . mean a better chance for mothers everywhere.”

Child health and welfare, child labor, and education also were addressed. The June 1932 issue featured the efforts in agricultural education and community service of the recently formed 4-H program and its contribution to development of leadership skills in young people. Following the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency in1932, Needlecraft commented enthusiastically on new White House programs to lift the country out of its Depression. The October 1933 issue spoke of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s support of the government’s program to hire unemployed artists and craftsmen to produce textiles, metalware, furniture, and other fine products for sale and characterized President Franklin Roosevelt as “an honest, able man, devoted to the welfare of his country.” It continued, “[I]f we will but do our part, each and every one of us, hoping for the best, believing in the best, standing back of our President in thought and word and deed, and lending a hand to help another, if need be, there is no manner of doubt as to results.”

In February 1935, the magazine urged every mother to cultivate compassion and tolerance in her children, and to discourage discrimination:

We must all live in the world at our door, and it may prove a mighty lonely place if we shut off from ourselves by foolish distinctions those who might become our best friends. Children of every race and creed must mingle here in America, and no ill will should be engendered among them. . . . Tell the little son or daughter that once upon a time every one in America came from one of the old countries across the sea. . . . With each came hopes, aspirations, the longing for a better life in the new land; but also came the long line of tradition and culture, a gift from that older country he was leaving behind. If each little American, as he grows, makes the most of [his] heritage, and appreciates the fine points of his neighbor, there will be much to learn and enjoy.

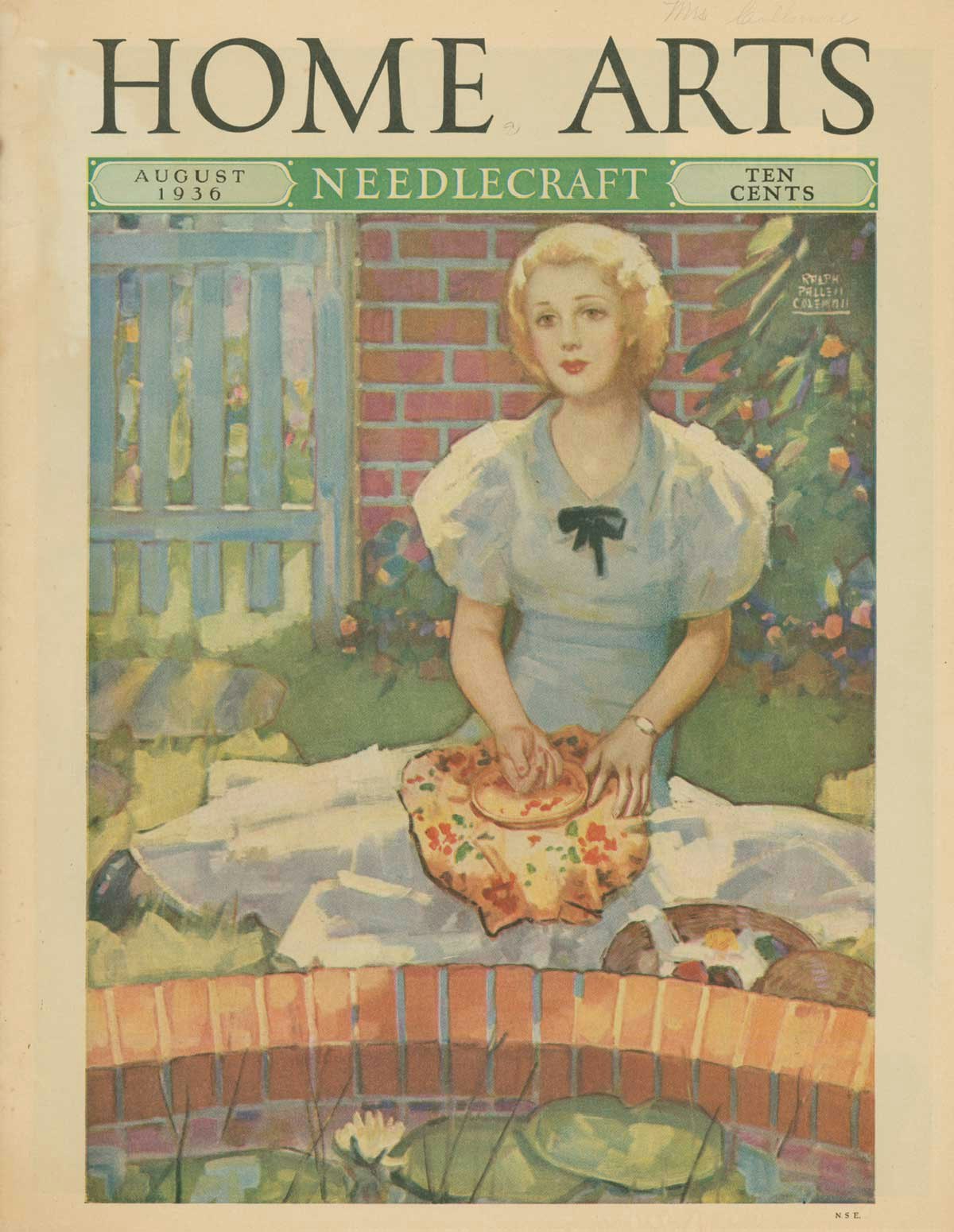

Cover of the August 1936 issue of Home Arts Needlecraft magazine.

The March issue highlighted the problem of child labor and explored the pros and cons of a proposed amendment to the Constitution:

“You and I will probably be called upon later to vote to either ratify or defeat this resolution; so it is not too soon to be thinking the matter over, that we may make up our minds on which side of the controversy we wish to be found. In any event we can all undoubtedly agree that every child has an inalienable right to leisure, wholesome recreation, opportunity for education, and freedom from adult cares while he is growing, and before he has reached his maturity. It is not only for his welfare but for the future welfare of the nation in which he lives, that this should be possible. That is a consideration we should not overlook.

Educational equality was the editorial theme in the September 1936 issue of Home Arts—Needlecraft. While editors acknowledged the rise in school attendance, they pointed out that cuts in appropriations were limiting access to school transportation and that many families couldn’t even afford shoes so that their children could walk to school. Readers were encouraged to contribute to remedies for these inequities and even nudged to demonstrate the “courage and the vision to enter public affairs,” perhaps alluding to the accomplishments of both Eleanor Roosevelt and America’s first female cabinet member, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins.

In August 1936, a key debate centered around the Townsend Plan, an “old age” pension supported by a national sales tax that would provide elderly individuals with $200 per month—no small sum by depression standards. Home Arts—Needlecraft readers were encouraged to take the plan to heart:

We have for once grasped the import of the direct and immediate personal application of this particular plan rather than considered it remote and indefinite, which one is apt to do with most public questions. . . . Quite aside from the money aspect this may well have been a good thing. Certainly if it has in any way helped us all to see that public affairs and national problems do have a personal bearing on each and every one of us, it may well be worth the cost. . . .

Although the Townsend Plan did not succeed in its original formulation, it ultimately led to the development of Franklin Roosevelt’s Social Security program.

After women had earned the right to vote, their broadening impact on national affairs was undeniable. Needlecraft and The Modern Priscilla acknowledged these changes. And, although ostensibly devoted to domestic arts, they took every opportunity to urge their readers to look beyond the home and remind them that, in fact, “the pin is mightier than the sword.”

Needlecraft and The Modern Priscilla

Needlecraft (known from 1935 as Home Arts—Needlecraft) was published from 1909 to 1941 in Augusta, Maine, and New York by Vickery and Hill and later by Needlecraft Publishing. Priscilla Publishing Company of Boston, Massachusetts, published The Modern Priscilla from 1887 to 1930. Copies of both magazines are frequently offered for sale on the Internet. —M. D. B.

Mary Dickinson Bird's longstanding interest in textile traditions and history took a new turn when her doctoral dissertation research on entomologist, educator, and early environmentalist Edith Marion Patch (1876–1954) revealed that the scientist’s sole domestic skill was needlework.

This article was pubblished in the March/April 2010 issue of PieceWork.