In November 2015, BookPage published an interview with Delia Ray about her children’s book Finding Fortune. The idea for the story sparked when Ray visited the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum in Sanibel, Florida, and saw some clamshells with round circles punched out of them. These shells came from Muscatine, Iowa, a city about 45 minutes from her home. At the museum, Mrs. Ray discovered that Muscatine had a rich pearl-button history, and she incorporated a slice of it into her book.

After reading this interview, I was intrigued to learn more about this subject. My research revealed that Muscatine was, at one point, the pearl-button capital of the world. People would camp on the banks of the Mississippi River to fish out clamshells. Then, factory workers would operate circular saws to cut discs out of them. These discs were sanded to make the perfect button for a dress or jacket. For more than a decade, the pearl-button industry skyrocketed. In 1905, factories in Muscatine produced more than 1.5 billion buttons. The industry employed one-third of the town’s population. It created fortunes and fed families during the Great Depression. Many historians find this pearl-button fever similar to the Gold Rush.

The Invention of the Button

Before buttons were invented, our primitive ancestors used thorns, sinew, and bone or metal stick pins to hold their clothes together. The ancient Greeks and Romans wore buttons made of bone, horn, shell, wood, and bronze primarily to decorate belts. The earliest known button was found in the Mohenjo-daro region of the Indus Valley (modern-day Pakistan), and it’s about 5,000 years old.

Functional buttons appeared in the Middle Ages when they became popular as fasteners. People wore them to fasten their clothes snugly and accentuate the lines of the arms in men and the bosom in women. Buttons represented prestige and prosperity; only the rich could afford them. The lower classes were forbidden to wear them. However, the Industrial Revolution changed that. Buttons were mass produced cheaply, and everyone could afford them. In the twentieth century, buttons were mass produced from plastic, a material cheaper than bone; wood; metal; or glass.

Button-Obsessed

In North America, the button industry began with John F. Boepple, a German craftsman skilled in making buttons from horns, hooves, bone, and seashells. Pearl buttons in particular were Boepple’s best seller. In 1879, Germany imposed a new tariff on imported oceanic mother-of-pearl that hurt Boepple’s business. Boepple had heard from a friend in the United States about the freshwater mollusks in the Mississippi River that produced mother-of-pearl. He hypothesized that the riverbed would be carpeted in mussels, and in 1888, he sailed to the United States to find his fortune. In the beginning, he worked as a farm laborer in Iowa. In his spare time, he built a button-making machine. He fished mussels by himself, cut buttons out of them, polished, and sold them.

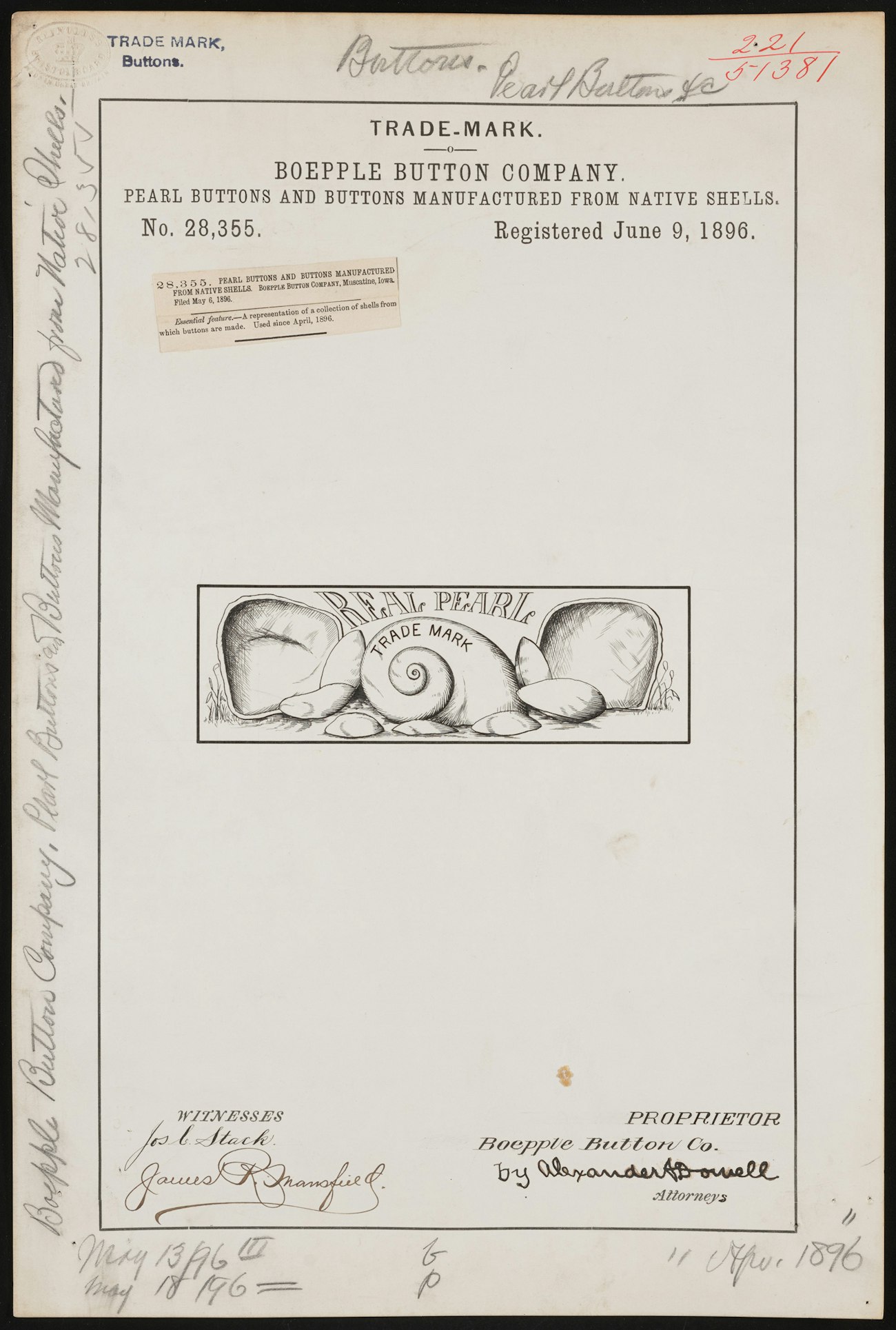

Trademark registration by Boepple Button Company for Real Pearl brand Pearl Buttons and Buttons Manufactured from Native Shells. ID Number 2023705804. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Trademark registration by Boepple Button Company for Real Pearl brand Pearl Buttons and Buttons Manufactured from Native Shells. ID Number 2023705804. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

In 1891, he opened the Boepple Button Company, a one-room factory, in Muscatine where the supply of mussels was plentiful. The company was such a success that it moved to a bigger building the next year. By 1908, Boepple’s business was booming but so was competition. Some of Boepple’s workers stole his techniques and went to work for other businesspeople. Soon other towns along the Mississippi River “adopted” Boepple’s button-making method and opened new button factories. Also, the advent of electric machinery replaced people-powered machines. Within 10 years, Muscatine or Pearl City became the largest manufacturer of freshwater-pearl buttons. Unfortunately, in 1909 Boepple was put out of business.

No More Clamshells

In the late 1930s, fishermen reported a scarcity of shells near Muscatine. So they harvested shells from new riverbeds in states such as Arkansas, Ohio, and Tennessee, and shipped them to Muscatine. Without shells, the button industry would collapse. To avoid such a disaster, in 1908, the federal government had set up the Fairport Federal Hatchery biological station in Muscatine to research and re-populate the Mississippi River with mussels. Boepple went to work for the federal government as a shell expert to help with the mussel propagation. Now instead of taking mussels from the river, he wanted to give back. He spent hours wading in the water, watching these creatures, and cataloging their behaviors until one day in 1912, he cut his heel on a sharp shell, contracted a blood infection, and died at Bellevue Hospital in Muscatine shortly after.

The Hatchery had hoped to produce enough mussel larvae to restock the riverbeds and sustain the pearl-button industry. Unfortunately, all the industrial button waste and the city sewage polluted the river waters, and the mussels died out. Soon after, the invention of plastic material replaced pearl buttons, and the industry declined. Pearl buttons couldn’t withstand modern washing machines, detergents, and cleaning chemicals the way that plastic could.

Making Pearl Buttons

When Boepple opened his first pearl-button factory in 1891, he found thousands of mussels bedded in the mud of the Mississippi River. At that time, there were more than 300 species of mussels. Boepple hired fishermen called “clammers” to mine these mussels. One way to do this was to “pollywog” in shallow waters, meaning the clammers felt for mussels with the soles of their bare feet. In deeper waters, they dragged a bar with wire hooks on the bottom of the river. When one of these hooks touched a mussel’s open mouth, the mussel slammed shut in defense and held on to the hook.

Then, the clammers pulled their catch onto their boats and removed them from the hooks. To kill them, they threw them in big vats of boiling water, pried the shells open, removed the whitish meat, and searched for pearls. Afterward, they threw the muddy-tasting meat back into the river, or used it as fish bait, fertilizer, or feed for livestock. Eventually, farmers realized that the meat of the mussel-fed livestock tasted like the Mississippi River, and they stopped using it.

From the riverbank, the shell buyers used wagons to take the mussels to the button factories where they soaked them in water for about a week to soften their shells. This prevented the shells from breaking while drilling them. A circular saw cut circular pieces, called “blanks,” out of the shell. This was a skilled job done only by men. A skilled cutter could cut as many blanks out of a shell as possible. The next step was to sort out the blanks, sand off the “bark” with emery wheels, and polish them. A machine carved a design on the face of each blank and cut two or four holes in them. The last step was to sew the buttons on cards or place them in boxes and ship them to retailers for sale.

Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History via Wikimedia Commons

Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History via Wikimedia Commons

Waste Shells and Dust

As button factories and family cutting businesses emerged in Muscatine, tons of leftover shells accumulated in alleyways. Something had to be done about the waste shells and shell dust. New machines such as the Double Automatic were invented that suctioned the shell dust. The leftover cut shells were used to pave alleyways. Farmers used shell chips and dust as a natural insecticide, grit for chickens, and plant fertilizer.

George Gebhardt, a creative Muscatine native, opened the Universal Shell Company and made a fortune out of waste shells and dust. He found out that the dust could be used as a mineral supplement for animals and that shell chips could decorate flowerpots and fishbowls. Other businesspeople made tableware, accessories, jewelry, and other novelties from the iridescent shells. Some other companies used the shell scraps to decorate belts and hairpins, make sequins, and more.

Working conditions in cutting shops were unsanitary and uncomfortable. All the machinery was made with production in mind and not safety. For example, buckets of cut shells, saw files, and other tools were scattered in work areas, while shell dust covered everything. Workers breathed in the shell dust, harming their throat and lungs. They cleaned machinery in motion risking cutting their fingers. Tiny flying shell particles caused eye injuries. The water needed to control the dust during cutting shells drenched the workers. Also, standing in the same position all day long was uncomfortable.

With the decline and end of the shell industry in North America, tons of shell leftovers were sold to Japan for use in the cultured pearl production. The implantation of a tiny shell bead into the oyster produced a valuable pearl.

Short-Lived But Significant

Mussel harvesting in the towns along the Mississippi River in the 1900s was a short-lived historical event in North America. It began in Muscatine, Iowa, in the late 1800s, when John Boepple opened his first pearl-button factory. Other businesspeople followed suit, and they made a fortune producing buttons out of freshwater mussel shells. For several decades, Muscatine reigned as the Pearl Button Capital of the World and employed thousands of men, women, and children. Sadly, mussel depletion and mass production of plastic buttons led to the decline of the pearl-button industry.

Resources

- Bonney, Margaret Atheron. “The Pearl Button Story.” The Goldfinch 2, no. 2 (November 1980), pp 11–13. paperzz.com/doc/9285549/the-goldfinch--vol.-2--no.-2--november-1980-

- Castellitto, Linda M. “How Iowa Lost Its Buttons.” BookPage. 2015.

- Cook, Harrison. “A Sift Through the Remnants of Iowa’s Forgotten Fashion Scene.” Atlas Obscura, September 11, 2019. atlasobscura.com/articles/pearl-buttons-muscatine-iowa

- National Pearl Button Museum. Muscatine, Iowa. muscatinehistory.org/

- “The Pearl Button Story.” Iowa PBS. iowapbs.org/iowapathways/mypath/2697/pearl-button-story

Harikleia Sirmans is known for her many talents. Among other things, she’s an academic librarian and an expert dressmaker. She loves sewing and needlework, and every evening, she crochets to relax. She was born and raised on the island of North Evia, Greece. Today, she lives with her husband in Valdosta, Georgia, and she makes beds, sweaters, and collars for their furry kids. Visit her at grecianneedle.com.