Editor’s Note: This is the last article in our series about author, knitwear designer, and amateur historian Sheena Pennell’s mission to re-create and adapt several pieces of Eleonora di Toledo’s wardrobe. (Read all of Sheena’s previous articles here.)

For most of her adult life, Eleonora di Toledo (1522–1562) was not in particularly good health. She suffered from tuberculosis, and 11 pregnancies left her body low in valuable nutrients, such as calcium and vitamin D.

By the time she and two of her sons (19-year-old Giovanni and 15-year-old Garzia) went to Pisa in 1562, the tuberculosis was taking its toll. In the final portrait painted during her life (see image at top), the difference is marked in the thinness of her face and sallow coloring. In her posthumous portraits, the artist Bronzino (1503–1572) used earlier works as references, bringing her back to the life and vigor she had when she first married Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574), as demonstrated in this image at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Examining the Burial Gown

When Eleonora’s burial gown was first examined, it was found that she had been dressed in a hurry, not at all with the care normally given to one of her station. This would have been done by her ladies as a final service to their patron, but the fear of contamination was great. Eleonora and her sons arrived in the city in the midst of a malaria outbreak (both sons died of malaria before her). At the time, nothing was known about how the disease spread, and it was feared that anyone handling her body would be contaminated. Normally, a woman of her station would wear 3 to 4 layers in public, but to save time, she was dressed only in her under dress—worn over a chemise and petticoats and underneath a more elaborate velvet gown/coat—and bodice. Besides fear of contamination, the value of her clothing could account for how scantily she was dressed; she no longer had use for elaborately embroidered gowns, and they would be a valuable inheritance for those left behind.

Eleonora’s velvet bodice was thrown on, the sides overlapping by more than an inch, displaying just how much disease had ravaged her body in her final days. The person who laced her in skipped grommets, clearly not caring how she was laced in, only that she appeared to be properly dressed when she arrived in Florence.

One thing that has made my job difficult on the reproduction side is that one of her stockings was put on inside out, but which one? Which side is the public side? The pattern is a combination of simple knit and purl stitches with a few yarnovers thrown in at the cuff; aesthetically, the stockings could be worn either way, with the cuffs standing or rolled down to cover a garter. Because of the state the stockings were found in after her bones had been removed, with the information we have, it’s almost impossible to tell how the stockings were worn, so I’ve had to make my best guess based on the images and information available.

The author’s reproduction of Eleonora’s burial stockings in progress. Photo courtesy of the author

Two silk strips were found among Eleonora’s clothing. Scholars are divided on whether they were meant to tie her hands and feet in the casket, since her body would have to travel some miles to be returned to her husband in Florence and conceivably they didn’t want her flailing around in her coffin. The other thought is that they could be the garters that held up her famous silk stockings—a strong contender because 100-percent silk stockings would be unlikely to stay put on their own.

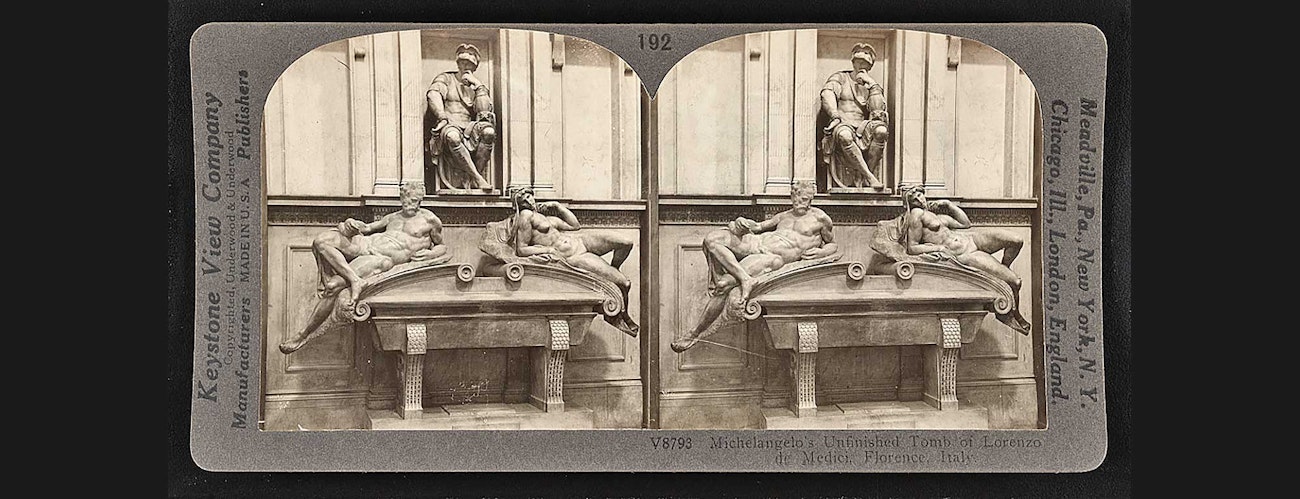

Michelangelo’s unfinished tomb of Lorenzo de Medici, Florence, Italy. Keystone View Company, Publisher. Stereoscopic image of the interior of San Lorenzo, showing the tomb of one of Cosimo’s ancestors. Cosimo and Eleonora are buried in the floor nearby, marked with simple engraved marble tiles. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Though Eleonora’s bones have been reinterred, her clothing shows great detail about her death and final days, as well as the fears and priorities of those who traveled with her and prepared her for travel and burial.

Sheena Pennell is the author, editor, knitwear designer, and amateur historian behind KnotMagick Studios. She has studied art conservation with an emphasis on textiles in Florence, Italy. The Eleonora project is based on a portion of her thesis, which focused on the challenges facing conservators working with burial garments.

If you are interested in following Sheena’s progress on The Eleonora Project and the reproduction historical garments she’s making, visit The Eleonora Project website.