I was in a Colorado antiques mall in the late 1990s when a colorful woven blanket caught my eye. It was made of squares of vivid colors—orange, burgundy, blue, green, lavender, pink—that were joined with black crochet, and they reminded me of light streaming through stained-glass windows. I unfolded the blanket and felt the childhood thrill of opening a fresh box of crayons, one of those large boxes with a dazzling assortment of 120 colors.

I bought the blanket, and I was happy that I had rescued another vintage textile. I studied the 204 individually woven squares: the choice of colors struck me as unusual and suggested the use of four-ply worsted-weight wool yarn left over from other projects. I saw an artist’s eye at work. Both the colors selected for warp and weft in each square and the arrangement of the colorful squares were well-thought-out. There was no moth damage; the only flaw was a break in the orange shell-stitch crocheted edging.

Pin Looms

The squares for the blanket had been woven on a pin loom, which is most commonly a 4-inch loom with blunt pins set into a plastic frame. During other wanders through antiques malls, I had collected four Weave-It looms (the most common brand of pin loom) in their original boxes—three four-inch-square looms made by Donar Products in Medford or Winchester, Massachusetts, and a more recent two-inch-square loom from Hero Manufacturing in Middleboro, Massachusetts. Each loom had basic instructions for sewing and assembling the squares. Only one box still had its long weaving needle, but another included a pattern book—one of five published by Donar, dated 1938.

An assortment of vintage pin looms and their packaging, from the author’s collection.

An assortment of vintage pin looms and their packaging, from the author’s collection.

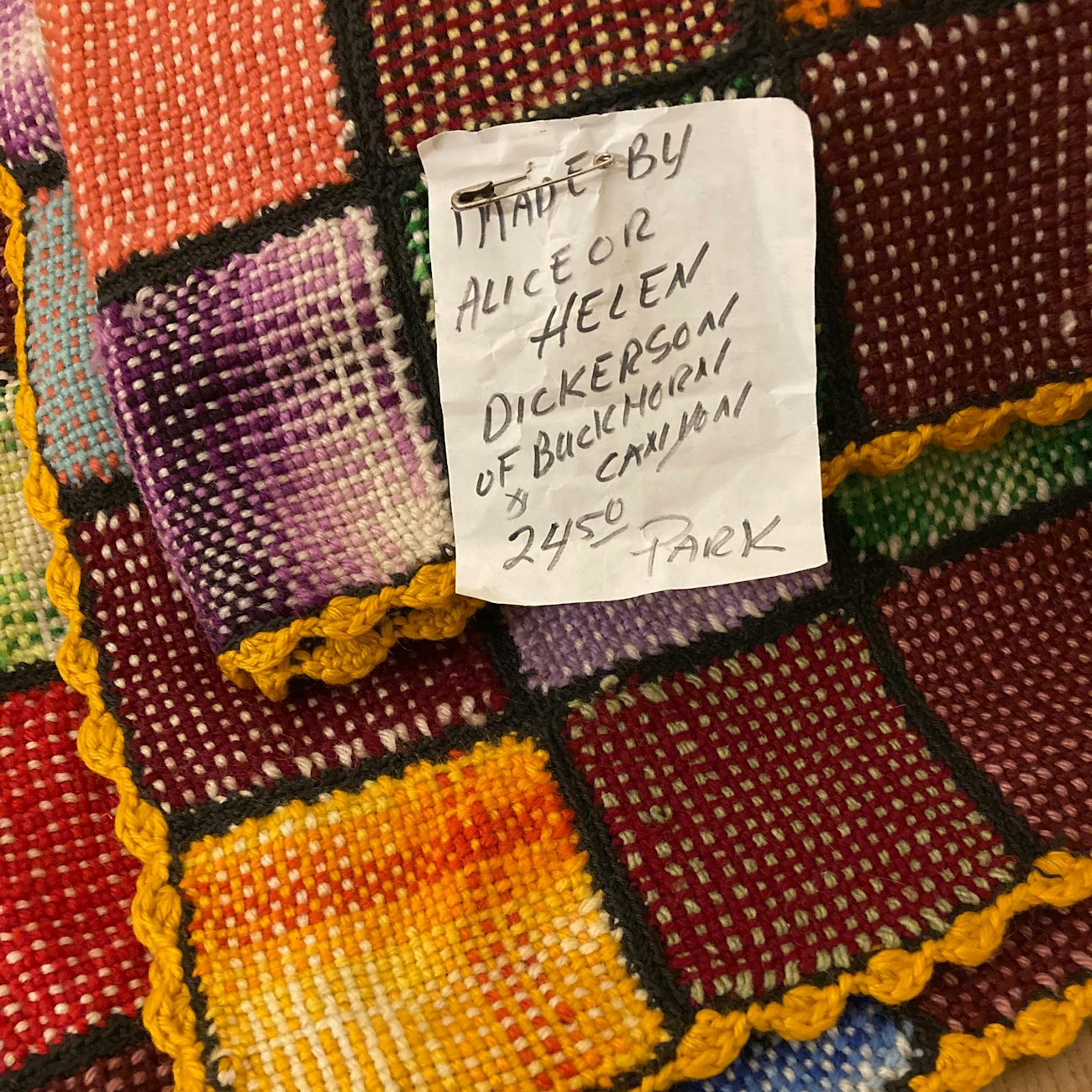

The popularity of pin looms began in the Depression-era 1930s and continued into the 1960s. My patent search dated the earliest loom to Donald R. Simonds for his “Yarn and the Like Supporting Device,” granted August 20, 1935, and assigned to Donar Products. Promotional claims on boxes and patterns emphasized the ease and economy of making dresses and coats, blankets and pillows, baby and doll clothes on a pin loom with slogans like “It’s So Simple!” and “Weave-It uses twenty to forty percent less yarn.” The blanket and little looms were interesting in themselves, but I was more intrigued by the handwritten note pinned to the blanket: “Made by Alice or Helen Dickerson of Buckhorn Canyon $24.50 Park.”

Familiar names, but exactly who were Alice and Helen Dickerson?

Finding the Dickerson Sisters

It soon became apparent to me that the Dickerson sisters were legendary in Colorado. Alice Cora Dickerson (1908–1997) and Helen Esther Dickerson (1909–1992) lived their long lives on land that their parents and grandparents had homesteaded early in the twentieth century, land in the Buckhorn Canyon, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains’ Mummy Range. After their mother, Stella H. Dickerson (1884–1964), and father, Earl Ross Dickerson (1879–1942), passed away, the sisters lived in the family cabin on their own, well into their eighties. I discovered their stories in newspaper articles, museum collections, family letters, a travel journal, and a biography.

Life had not been easy for the Dickerson family. Living at an altitude of 8,402 feet, they faced weather that could change in a heartbeat from sunny and glorious to harsh and violent. The average snowfalls reached 11 feet. Floods washed out canyon roads. Drought plagued the area during the thirties.

The family lived off the land but relied on other ways to make a scant living. They kept dairy cows, rabbits, chickens, and a few sheep, goats, and horses. With livestock and a large garden, they sold and bartered produce, eggs, and dairy products. They took in boarders, usually road crews, Forest Service, and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers. They built a sawmill in 1918, which was a major source of income, and they made the posts and poles that were necessary supplies for farms and ranches.

Their cabin had no modern conveniences—no electricity, refrigeration, or plumbing—simply an icehouse, outhouse, and wood-burning stove. “We never had it, so we don’t miss it,” Alice always said. By the late 1920s, they were able to listen to broadcasts on Crosley radio earphone sets and follow national news—like the Lindbergh baby kidnapping—from as far away as Tennessee. They did have a telephone by 1930 and, eventually, friends built an indoor bathroom for their cabin.

Hard work was part of life for the Dickerson family. At very young ages, Helen and Alice were put to work leading horses that pulled tree stumps to clear land for growing food. With few toys or other children around, the sisters learned to entertain themselves at home. As they grew older, Helen milked the cows and Alice fed them, separated the milk, and made cheese to sell. In 1933, Alice also delivered the U.S. mail in their mountain area. She turned to trapping—coyotes, bobcats, foxes, ermine—to earn badly needed cash during the Depression years. Both sisters worked in the sawmill.

The Dickersons were no strangers to the concept of use it up, wear it out, or do without. Alice remembered using feed sacks—cloth that held animal feed—for makeshift overshoes worn in the cold and snow. Sacks were folded under shoes for thickness, wound over shoe tops and up trouser legs, then tied in place with heavy twine. The overshoes did not wear well but kept feet warmer.

Their mother, Stella, took great care in sewing dresses for her daughters on her Singer treadle sewing machine. She repurposed adult clothing for them. With an artistic flair, she also stitched quilts, wove rag rugs, and hooked rugs inspired by her Buckhorn ladies’ club and women’s magazines.

The sisters had seven years of on-again, off-again schooling beginning in 1917. They and their mother stayed during the school year in a house in the tiny community of Masonville, which was 24 miles down the canyon from their home, and the girls attended classes in a one-room schoolhouse. In 1923, a severe flood reduced the Buckhorn Canyon road to a rocky creek bed that isolated the sisters at home for two years. Their mother resorted to correspondence courses with lessons that were carried by horseback through the Masonville post office. Both sisters attributed much of their education to lessons learned in the “school of hard knocks.”

During the 1930s, Helen and Alice enjoyed outings with other young people—cookouts, dances, box suppers, fairs—and each had suitors but never married. Late in life, Alice claimed their father drove off the boys, afraid of losing his daughters (and perhaps his hired help).

The Golden Eagle

In 1931, Helen and her father built a stand they called The Golden Eagle near their cabin to sell handcrafts that she, Alice, and Stella made during winter. Tourists were arriving in the region, drawn to stays at local “dude” ranches, and equally welcome were the Forest Service and CCC workers. Fort Collins residents also drove up the Buckhorn Canyon to buy handcrafts from the Dickersons, especially Helen’s handwoven baskets. Helen made postcards to promote The Golden Eagle.

Helen put the native plants of the forest into her baskets, and Alice painted scenes from the natural world around her. Helen’s willow-bark and pine-needle baskets and the bolo ties that she fashioned from elk antlers were in high demand. Alice painted mountain landscapes and the wildlife that she loved onto wooden panels and goose eggs. She painted elk among pine trees, chipmunks and butterflies, hummingbirds and columbine flowers, gray squirrels, and raccoons. Alice and Helen collaborated on some pieces. Alice painted a scene from the natural world on the wooden base of Helen’s handwoven basket.

After Helen died of cancer, in 1992, Alice lived on her own in her Buckhorn Canyon home. She lighted her cabin with gaslight, baked bread on a wood stove, watched nature programs on her solar-powered television, and, with the help of friends, planted her garden and gathered firewood.

Helen, a homebody, had been content with her life and handcrafts in the high country. Alice, on the other hand, always had a sense of adventure and was curious about the world outside Buckhorn Canyon. (As a toddler, she had a habit of running off, so her mother often tied her to a doorknob.) It was Alice who learned to drive and bought her first car, a 1928 Plymouth coupe—later traded for a 1936 pickup that she drove for 39 years.

Well into her eightieth year, Alice began traveling. Her journalist friend Elyse Deffke Bliss lured Alice to Alaska with the promise of seeing wildlife. In Alaska, Alice thrilled to the sight of Dall sheep on the Kenai Peninsula. She experienced her first jet plane and train rides, flew in a helicopter over Denali Park, fished for salmon, visited a muskox farm, and took a small plane to walk on a glacier.

Alice and Elyse traveled to the Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, Devils Tower, Dakota Badlands, Mount Rushmore, and a black-footed ferret research station. They saw Kaibab squirrels on the rim of the Grand Canyon and thousands of migrating sandhill cranes in Nebraska.

In 1995, Alice and Elyse traveled with friends to Zimbabwe. Alice encountered—at times more closely than she expected—the dazzling array of African wildlife, from leopards, hippos, elephants, and zebras to wildebeests and baboons. The array of bird life astonished her. She traveled by plane, Land Rover, dugout canoe, motorboat, shuttle bus, river barge, and, briefly, elephant. Her last journal entry reads, “The trip was most wonderful. I loved it.”

In September 1997, Alice lost her third bout with lymphoma. She was laid to rest in Grandview Cemetery in Fort Collins, Colorado, near her sister and parents. The Dickerson cabin and outbuildings on US Forest Service land were torn down and their possessions sold at auction, in accordance with an agreement made years earlier with Helen and Alice.

Did Helen or Alice Dickerson weave the pin loom blanket? After extensive reading, I have found no reference to either sister weaving with a pin loom. Alice was drawn to painting, the outdoors, and wildlife, Helen to making baskets and other handcrafts from nature. As adults who were taught to not waste anything, could they have been tempted to use the scraps of yarn at home to keep themselves warm during the long winters?

The Dickerson pin loom blanket with the seller’s note attached.

The Dickerson pin loom blanket with the seller’s note attached.

Their mother, Stella, on the other hand, wove rugs and stitched quilts and clothing—and she was known to have an artist’s eye. I suspect Stella wove the pin loom blanket that her daughters displayed in their cabin as a fond memory of her. The many colors of yarn were a testament to many other knitted, crocheted, or woven projects.

The Dickerson blanket I rescued from an antiques mall has traveled safely with me to my homes in Illinois and Washington state. Now I plan to return the blanket home to Colorado, as a donation to the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery, where all who admired the legendary Dickerson family may enjoy the story of the pin loom blanket.

Interested in reading more about sentimental handmade pieces? This article and others can be found in the Summer 2024 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Summer 2024. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Archives of the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery.

- Bliss, Elyse Deffke, from interviews with Alice Cora Dickerson. Apples of the Mummy’s Eye: The Dickerson Sisters. Self-published, 1994, 1999.

- Fleming, Barbara. “The Dickerson Sisters, Buckhorn Canyon Legends.” Fort Collins Coloradoan. September 6, 2015.

- Fort Collins History Connection, an online collaboration between the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery and the Poudre River Public Library District. https://history.fcgov.com.

Pin looms have had a resurgence of favor among contemporary handcrafters. Long Thread Media publishes Easy Weaving with Little Looms, a magazine dedicated to their use.

Susan Strawn is professor emerita of Fashion Design and Merchandising at Dominican University (Chicago), a contributing editor to PieceWork, and author of Knitting America: A Glorious History from Warm Socks to High Art (St. Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2007). She researches and writes cultural histories of textiles and makers, with a particular interest in the history of American knitting. She lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington.