A hot, humid city on the coast of West Africa is an unlikely place to find a long tradition of making and wearing woolen needlepoint carpet slippers. In Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, however, distinctive hand-embroidered slippers are part of Krio women’s traditional dress, although they are time-consuming to make, expensive to buy, and totally impractical for the climate.

The Krio people are descendants of four groups of settlers taken to the colony of Freetown between 1787 and about 1830. The initial group arrived in February 1787 and was composed of about 350 blacks from London as well as some sixty-five whites from England who sought their fortune overseas. Most of these first settlers became victims of the climate, disease, poor soil, and an indigenous community that killed many and enslaved a few. In 1792, the Sierra Leone Company, a chartered association of British businessmen and benefactors whose aims included suppressing the slave trade and introducing Christianity along the coast of West Africa, organized an expedition of about 1,150 settlers for Freetown from Nova Scotia. These Black Loyalists were former slaves and indentured servants from the American colonies who had sided with the British during the Revolutionary War (1775–1783). They had spent the intervening years in dreadful conditions in Nova Scotia, where they never were given the land promised to them and largely were employed as farm laborers in a harsh climate with scant resources. The Maroons, arriving in 1800, were blacks from Jamaica who had revolted against British masters but were tricked into leaving their strongholds after a peace offer, captured, and removed to Nova Scotia and then on to Freetown. After Great Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807, British ships began stopping slave ships and shipping Africans taken from them—known as Liberated Africans or Recaptives—to Sierra Leone regardless of their actual place of origin.

Stripped of their original ethnic connections, these groups gradually formed a new culture with its own language, Krio (a combination of English and several African languages, as well as a smattering of other European languages, with a West African grammatical structure), customs, food, and distinctive clothing. Clothing, one of the principal features distinguishing the indigenous inhabitants from the settlers, played an important role in the development of Krio society and in the history of Sierra Leone. Krio women’s dress amalgamated influences of then-current Western fashion with influences from Colonial America, early-nineteenth-century London, and various African styles that the Liberated Africans had retained.

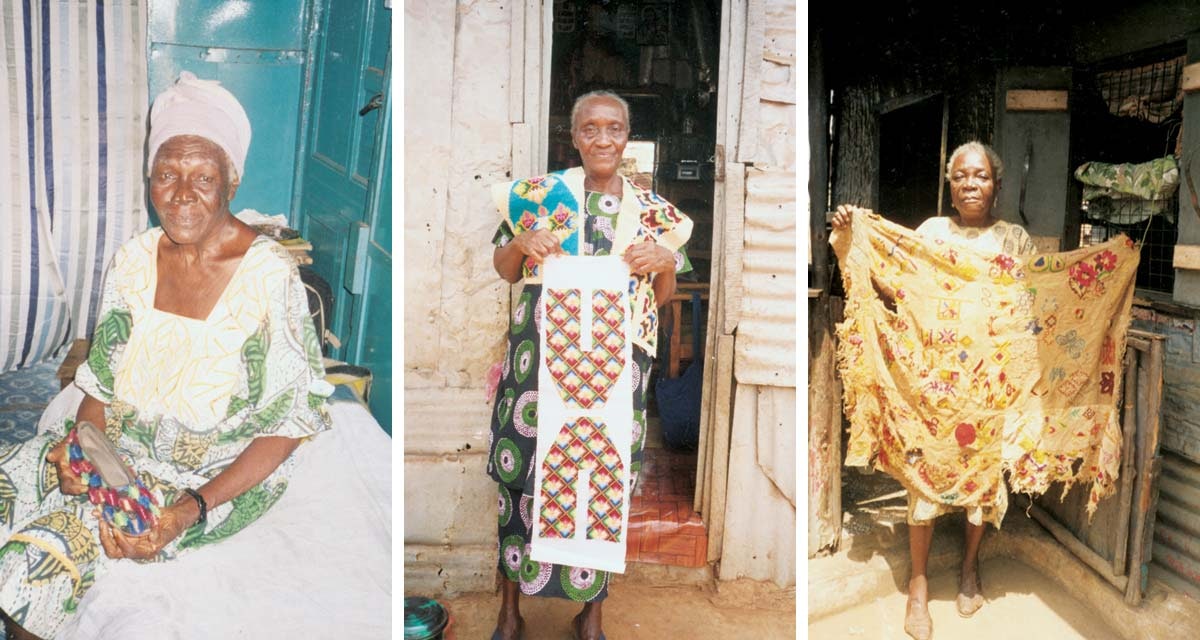

Left to right: Photo of “Grandma” Comfort Bull, holding a completed carpet slipper, in her house in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2003. Photo of Marion Wilson, holding a finished carpet slipper pattern, in front of her house in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2003. Photo of Claris Davis, holding her pattern canvas for carpet slippers, in front of her house in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2003. Photos by the author

By the late 1800s, carpet slippers had become an element of the Krio costume, but the exact origin of the slippers has not been determined. Such slippers were worn in England and America, and the techniques used to make them likely were brought to Sierra Leone with the settlers. From the outset, all the materials necessary to make the slippers had to be imported. Even when a new style of dress supplanted the old, as happened in the 1950s, the carpet slippers remained as part of the outfit.

Some of the designs, the bright colors, and the stitches (including tent and cross) used on the carpet slippers resemble Berlin work, a type of needlepoint worked on canvas that was popular in Europe throughout much of the nineteenth century (see “Berlin Work,” PieceWork, March/April 1995). Nevertheless, the resemblance seems only superficial as Krio embroiderers never use the patterns and color charts on gridded paper that are requisites of Berlin work.

In 2002, after finding no information about the carpet slippers of Sierra Leone in numerous museums, including The Textile Museum and the African Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Victoria and Albert in London, I began interviewing seven women in Freetown who still “marked” (embroidered) carpet slippers, using imported wool (sometimes, polyester) yarns on common needlepoint canvas, also imported. Each woman owns a number of old canvases that document the stitches and motifs used in her repertoire of patterns and serve as references for her projects. I borrowed four of these canvases, all of which have been handed down for generations, to chart the patterns.

The average age of the women I interviewed was eighty-two, and each said that she had learned to mark slippers from her mother, who had learned from her mother, and so forth back more than 100 years. No one whom I interviewed had any memory of a printed paper pattern or color chart. The pattern canvases I saw used the same names for the same designs on each canvas most of the time, although color variations for the designs were common. Each canvas, however, had a few patterns that were unique to it. New patterns were created if a client so desired and if the woman marking the slippers had the skill to draft a pattern that would fit a standard size slipper. I did not find any slippers that combined more than one pattern at a time.

Left: part of a pattern canvas in the family of Claris Davis, needlepoint, wool on canvas, Freetown, Sierra Leone, circa 1920. Right: part of a pattern canvas in the family of Doia Macauley, needlepoint, wool on canvas, Freetown, Sierra Leone, circa 1949.

Left: part of a pattern canvas in the family of Claris Davis, needlepoint, wool on canvas, Freetown, Sierra Leone, circa 1920. Right: part of a pattern canvas in the family of Doia Macauley, needlepoint, wool on canvas, Freetown, Sierra Leone, circa 1949.

As with American quilt names, the names of the patterns used on carpet slippers evoke history, everyday life, sentiment, opinions, and life circumstances. Some are named for natural objects such as clouds or cowrie shells. Others are named for fruits and vegetables, including mango, cabbage, yabas (onions), and “pear” (avocado). Many have Krio names: Bajuma Sawa-Sawa (bajuma, a very old woman who is always well dressed; sawa-sawa, a plant with edible leaves) and Troki’s Back (troki, a turtle).

Prince of Wales Feather commemorates the 1920 visit of the Prince of Wales to Sierra Leone. Annie Walsh School was designed in 1949 to mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the oldest secondary school for girls in Sierra Leone, which is still in operation. Designs that express opinions and circumstances include Work for No Man after Four; You Hook Me, I Hook You; Who Able Me? (Who Can Beat Me?); If You Love Me, Take Care of Me; and Confusion. Animal names, such as Eagle, Water Snake, Cocktail (a biting insect that lives under stones), Butterfly, and Scorpion, are among the most popular. Patterns named for everyday objects include Radio Box, Necklace, Granny’s Spectacles, Flower Pot, and Torch Light (flashlight). During my two-year survey of Freetown’s most accomplished “markers,” I found sixty-four different named pattern designs on pattern canvases.

The embroiderers whom I interviewed are considered specialists; they charge for their work according to the complexity of the design and the number of colors used. Comfort Bull, eighty-six years old in 2003 and known to all as Grandma Bull, told me that if you know how to mark slippers well you can vary a design as you wish or as a client wishes. Several of the women who mark canvases also told me that a woman never lends her pattern canvas to anyone else.

On average, it takes two weeks to needlepoint the fabric for a pair of carpet slippers. The finished fabric, called “houses” because of their shape, are then taken to a shoemaker to be lined, shaped, and soled.

When I first lived in Sierra Leone in the early 1970s, Krio clothing, including the carpet slippers, was more commonly worn in Freetown than it is now; women could be seen shopping, collecting children from school, and generally going about everyday activities in their distinctive Krio dress. By 2002, however, women in traditional dress were a rare sight, and even when you saw one, she would not be wearing carpet slippers. Today, carpet slippers usually are seen only on special occasions, such as wakes and funerals, wedding receptions, church meetings, and Saturday parties.

As it did with almost everything else in Sierra Leone, the eleven-year Civil War (1991–2002) devastated the carpet slipper tradition. If the imported materials can be found at all, the price to have slippers made is prohibitive, and cobblers are hard to find in Freetown since the war. And because the younger generation sees no profit in making the slippers, young girls are not learning the time-consuming craft.

With no new embroiderers being trained to replace the elderly ones, it is clear that the carpet slipper tradition is in danger of dying out. None of the women I interviewed had daughters or granddaughters who were interested in learning the skill. Perhaps as Sierra Leone continues to recover economically, politically, and socially from the effects of the war and the wounds begin to heal, a new pride in old traditions will revive, and among them will be the marking of Krio carpet slippers.

Interested in more embroidery? This article and others can be found in the July/August 2007 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including July/August 2007. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Davis, Louise. “Shoes and Embroidery.” Embroidery, Summer 1980.

- Porter, A. T. Creoldom: A Study of the Development of Freetown Society. London: Oxford University Press, 1963. Out of print.

- Wass, Betty M. “The Kaba Sloht: Women’s Dress and Ethnic Consciousness in Krio Society.” Paper presented at the African Studies Association and Latin American Studies Meeting, Houston, Texas, November 1977.

- Wyse, Akintola. The Krio of Sierra Leone. Washington, D.C: Howard University Press, 1991.

Lucille Chaveas has a master’s degree in Museum Studies from The George Washington University and is a National Quilting Association certified teacher. With her husband, Peter R. Chaveas, who served in the Foreign Service, she lived overseas for nearly thirty-seven years. Two of their postings were in Sierra Leone.

Originally published June 8, 2020; updated June 24, 2024.