Little known and now perhaps even extinct, the blue-and-white embroidery of rural China was the handwork of a people who lived close to nature and whose lives were steeped in myth and tradition.

For centuries, the peasants of western (now central) and northern China embroidered their white handwoven cotton cloth with blue cotton thread (or less frequently, blue cloth with white thread). The stitches ornamented all manner of household goods—pillow slips, mirror covers, bed valances, runners, bedspreads—in designs both symbolic and decorative. Young women embroidered articles for their dowry; other women made them as gifts for use in the new household. Women also embroidered caps and jackets, aprons and sashes, children’s bibs and collars, and other articles of clothing.

In small village shops, locally grown cotton was woven into cloth 12 to 25 inches (30.5 to 63.5 cm) wide. Embroidery thread was hand-twisted and dyed with indigo from the plant Indigofera tinctoria. From three to as many as five strands of thread were used at once. Cross-stitch was the most common stitch, but occasionally double-running stitch (called erh mien ti, “with two faces,” by the Chinese because the stitch is identical on both sides of the cloth) also was used. One unusual characteristic of these embroideries is that hems were turned to the front of the cloth, where they served as another border.

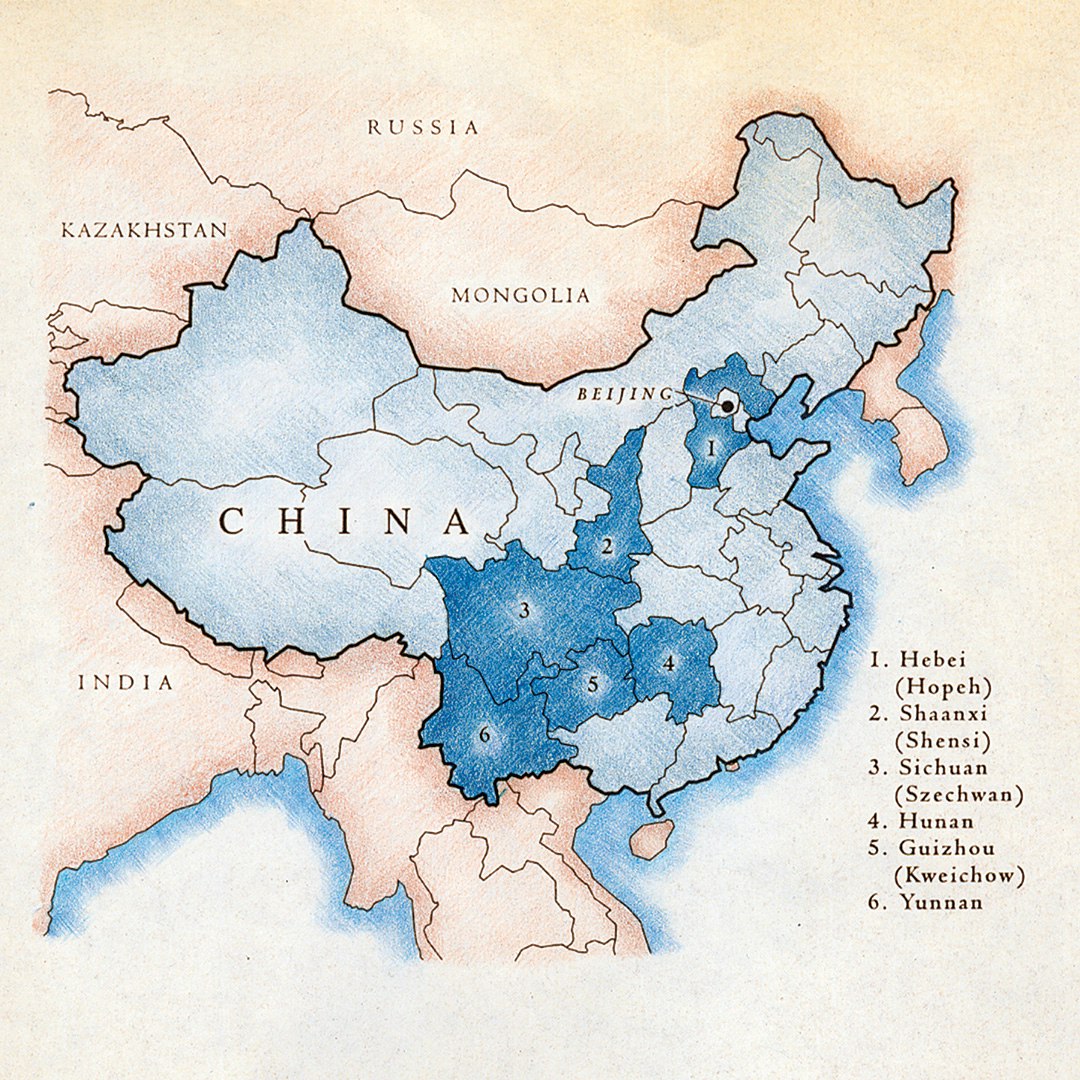

Researchers believe that this blue-and-white embroidery varied little over the centuries. It has been found in Hebei (Hopeh), Shaanxi (Shensi), Sichuan (Szechwan), Hunan, Guizhou (Kweichow), and Yunnan Provinces.

The Chinese provinces shown in dark blue are those in which blue-and-white embroideries have been found. Illustration by Ann Swanson

The Chinese provinces shown in dark blue are those in which blue-and-white embroideries have been found. Illustration by Ann Swanson

The embroideries themselves provide a library of symbols that the peasant needleworkers used. Some of the same symbols have been found on artifacts that date to China’s Tang Dynasty (618–906 CE) or even earlier. Tradition, nature, folklore, and superstition influenced the embroiderers’ repertoire of symbols. The blue-and-white embroideries were thickly populated by birds and other animals, plants, insects, fruits, and other motifs. Each motif had meaning and combinations of motifs created visual stories and puns: horses were emblems of perseverance; monkeys, of trickery; fish, of wealth, harmony, and marital joy. Apple blossoms represented beauty and peace; chrysanthemums, laughter and a life of ease. Peaches symbolized marriage, immortality, and spring; plums, long life and winter. A motif might serve as a talisman to ward off evil or attract good luck. For example, a rabbit similar to the one in the project was embroidered on a woman’s apron top to “eat” evil. Symbols might be worked singly, repeated in borders, or arranged in circular medallions.

Many symbols were handed down through families or were peculiar to a region, but others were accepted throughout China, and still others showed the influence of cultures from outside China, such as the “Buddha’s hand,” one of many religious symbols that came from India with Buddhism in the first century CE. Travelers from the Middle East and the Caucasus also left the imprint of their presence.

Interested in more of the color blue? This article and others can be found in the July/August 2012 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including July/August 2012. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Sue Lenthe is a freelance writer living in Colorado.

Originally published February 19, 2021; updated April 7, 2023.