“Cast off the shackles of yesterday, shoulder to shoulder in the fray. Our daughters’ daughters will adore us, and they’ll sing in grateful chorus: Well done, Sister Suffragette!” Surprisingly, these lyrics from the song “Sister Suffragette” do not date from latenineteenth-or early-twentieth-century Great Britain but were written by the American songwriters Robert B. Sherman (1925–2012) and Richard M. Sherman (1928– ) for the 1964 Disney movie Mary Poppins.

It is Poppins’s employer Winifred Banks who is singing about the fight for women’s suffrage and equal rights in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Great Britain. Behind the upbeat melody and cheerful dance number, however, lurks a darker, more interesting subtext: references to fighting “militantly” and a Mrs. Pankhurst’s being “clapped in irons again” reveal the good-natured Mrs. Banks as a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Founded in 1903 in Manchester, England, by six radical suffragists, including Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928) and her daughter Christabel (1880–1958), the WSPU began as a suffrage organization for those who considered the political tactics practiced by the constitutional suffrage movement ineffectual. Not the first radical suffrage group in Britain—many had come before it—nor the most liberal, the WSPU advocated only for equal suffrage rights for women, not universal suffrage. (Equal suffrage would have left many working- and lower-class women ineligible to vote due to property ownership requirments.) What set the WSPU apart from similar organizations was the length to which members would go to gain publicity for the women’s suffrage movement. The Pankhursts, tired of politely campaigning for women’s rights in a ladylike fashion, believed that suffrage would ultimately be won through “deeds, not words.”

Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the British women’s suffrage movement. 1910. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

These deeds started out innocently enough as acts of civil disobedience: marching in protests, holding open-air meetings, and in one case refusing to pay taxes. The jump from radical to militant came in 1905 when Christabel and fellow WSPU member Annie Kenney (1879–1953) interrupted a public political rally to demand support for women’s suffrage. This brazen act of speaking up in public while female caused an uproar, and police escorted the women out of the meeting. During their removal, Christabel deliberately assaulted the police officer so that she would be arrested, hoping that her arrest would bring publicity to the cause. Christabel’s tactic worked, and it marked the first of many arrests of WSPU members. (Emmeline Pankhurst’s first arrest was in 1908.) As Christabel served her one-week sentence (she refused to pay the fine), the press exploded with stories of police brutality against defenseless suffragettes. (Although newspaper journalists had coined the term “suffragette” to undermine the women’s suffrage movement, the WSPU readily adopted it. Today, when referring to the British women’s movement, “suffragist” is the term used to label those individuals and organizations that fought for women’s suffrage using traditional, nonviolent means, whereas “suffragette” is reserved for individuals or groups that used militant or violent means.)

The Pankhursts (who were by now the de facto leaders of the WSPU) encouraged members to continue with their protests, public meetings, and heckling public speakers. They believed that the fight was as important as the intended outcome. They did not wish that women be given the right to vote; rather, they wanted to win the right to vote. Members saw these small acts of rebellion as empowering, and their actions helped the WSPU get the attention of the media; however, the same acts elicited anger from many outside the organization. Some angry men attacked demonstrating suffragettes, and police frequently refused to intervene.

The first major schism in the organization took place just three years after its founding, when the Pankhursts decided to align themselves with more conservative politicians. Originally, the WSPU membership had consisted mainly of working-class women and supporters of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), a socialist political party (not to be confused with the Labour Party). In 1906, the Pankhursts decided to break off the connections to the ILP and focus on defeating the government candidate rather than on electing the ILP candidate. Most likely, their motive was to recruit more upper-and middle-class women. As Christabel put it, the House of Commons was “more impressed by the demonstration of the feminine bourgeoisie than of the feminine proletariat.” These new members not only had higher social status than did working-class women, they also were considerably wealthier and contributed greatly to the WSPU’s fundraising campaigns.

The split from the ILP and the recruitment of conservative, wealthy society women caused friction among members. Hoping to solve the problem and prevent similar policy changes in the future, executive committee member Teresa Billington-Greig (1877–1964) drafted a constitution that she would propose at the 1907 WSPU annual conference. Calling for the election of delegates to the annual conference who would vote on policy changes, the constitution would have made the WSPU a democratic organization. This proposal angered Emmeline Pankhurst, who tore up the document and canceled the meeting. Billington-Greig was furious, protesting, “I do not believe that a dictatorship can be right, even if it is . . . a dictatorship of angels. . . .” Along with several other WSPU executive committee members, she resigned and founded the Women’s Freedom League (WFL); about one-fifth of the WSPU membership followed.

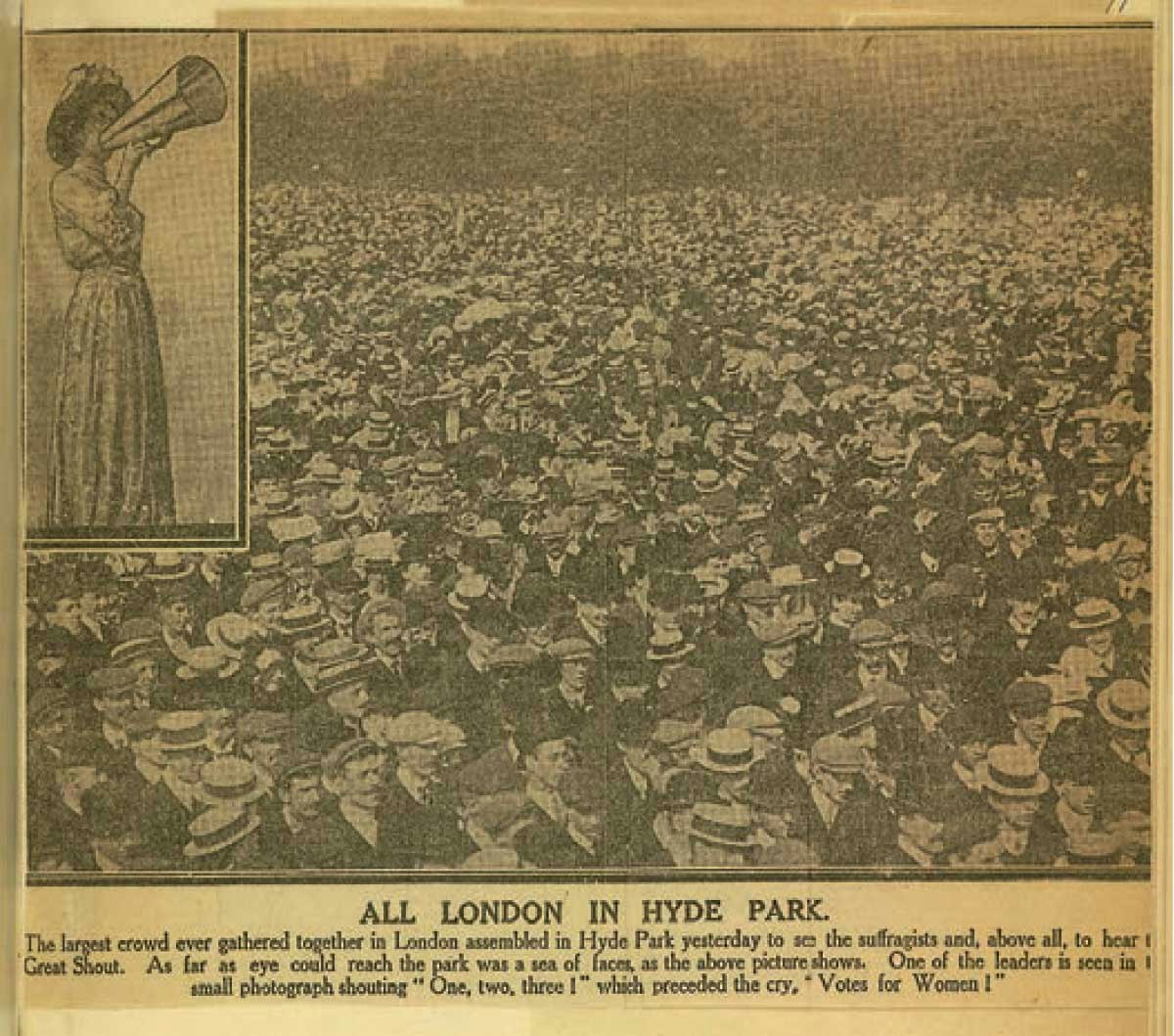

In 1908, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852–1928) took office as the new British prime minister. A longtime opponent of women’s suffrage, Asquith promised to support giving women the right to vote if it could be proved that a majority of women supported the notion and that the nation would benefit from women’s voting. In response, Emmeline Pankhurst and the poet and author Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme Elmy (1833–1918) led an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 supporters through the streets of London to Hyde Park for a rally to support suffrage.

A record-breaking suffrage demonstration in Hyde Park. London, England. Photograph published in the London Daily Express, June 21, 1908. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Despite this enormous display of support, Asquith continued his opposition to the movement, and the Pankhursts decided that the WSPU needed to escalate its militancy to damaging public property. In July 1909, Marion Wallace Dunlop (1864–1942), arrested for stenciling a passage from the Bill of Rights on the wall of the House of Commons, became the first British suffragette to go on a hunger strike. She fasted for ninety-one hours before being released for health reasons. More suffragettes followed Dunlop’s example and refused to eat while incarcerated. In September, forced feeding of the strikers was instituted. Outraged, the suffragettes responded with more violence, which resulted in more arrests and more hostility toward the WSPU and other militant organizations.

On November 18, 1910, the WSPU sent several hundred women to the House of Commons to protest yet another delay of the Conciliation Bill, a piece of legislation that would have granted property-owning women the right to vote. When these protestors rushed the police lines, they were not quickly and efficiently arrested as they had been previously; instead, police assaulted the women over the next six hours, injuring many of them. Some women also were groped in an apparent attempt to shame them into submission. If the police thought that this would silence the suffragettes, they were wrong. Many of the participants later declared that the response of the police only encouraged them to be more violent and destructive in the future to ensure a quick arrest rather than risk further abuse. Still, new actions were limited to relatively minor acts of vandalism against public property, such as graffiti and breaking windows. A new level of destruction began in 1912 following the failure of the Conciliation Bill in 1910 and 1911. The Pankhursts believed that if the WSPU caused enough chaos and destruction, the public might pressure the government into voting for women’s suffrage as a way to return to order. Members set fire to houses, a school, two teahouses, and about fifty churches. A painting at the National Gallery was vandalized, and bombs were set off. Although the extent of the Pankhursts’ control over the vandals is debatable, the Pankhursts publicly praised their actions. These extreme acts of destruction nevertheless caused many women to leave the group.

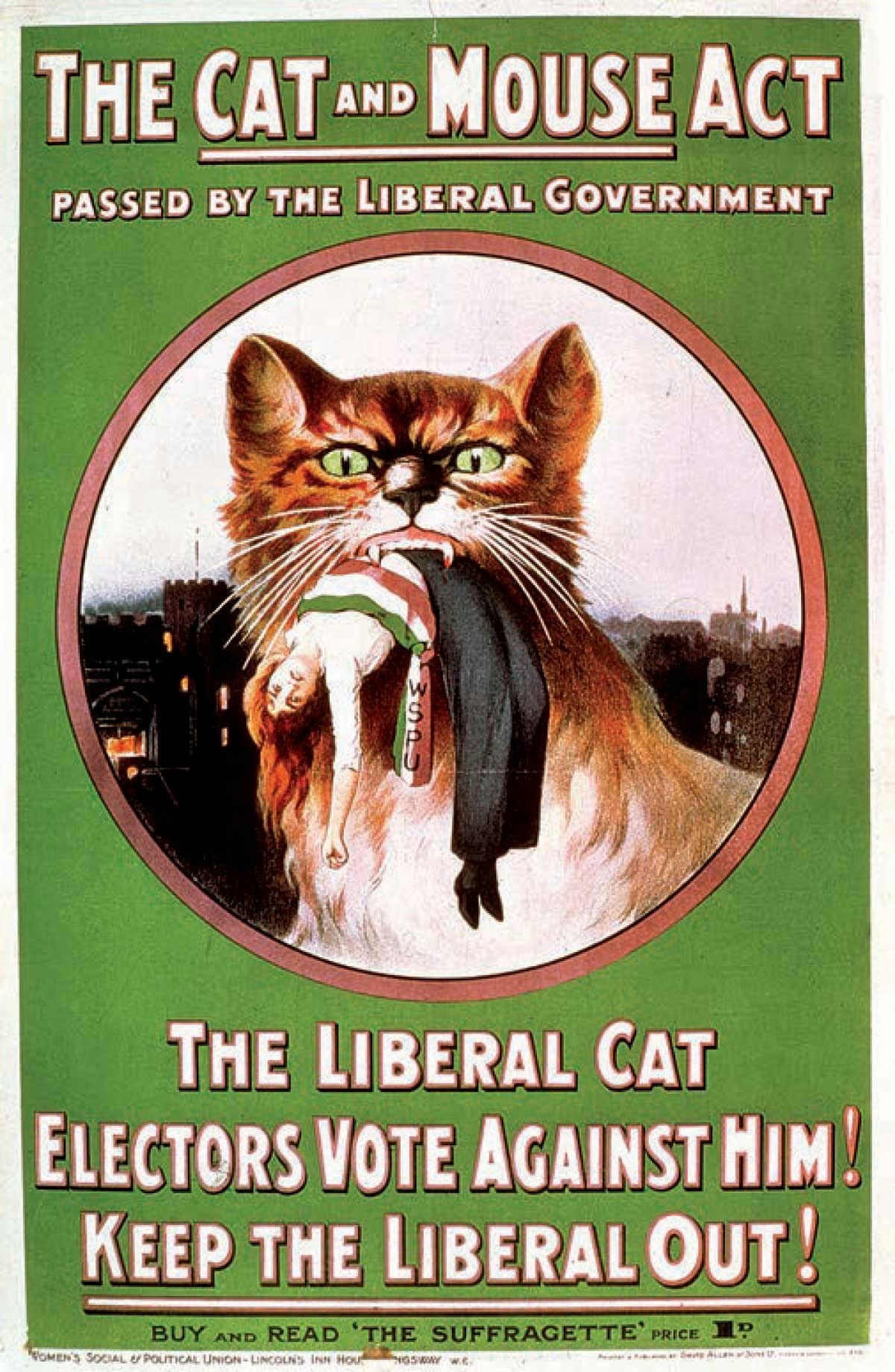

Furthermore, hostility toward the WSPU grew, and their destructive acts distracted the public and policymakers from the cause of women’s suffrage. Still, the violence continued, and so did the arrests and hunger strikes. Although forcefeeding prisoners was legal, many of them later wrote about the painful, violent experience, causing public outrage. Far from reducing the number of arrests of suffragettes, the outcry led to the passage of the Prisoners Temporary Discharge (for Ill Health) Act 1913. Also known as the “Cat and Mouse Act,” this piece of legislation allowed prisoners on hunger strikes to be released due to ill health and then rearrested after their recovery.

A 1914 Women’s Social and Political Union poster refers to the Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge (for Ill Health) Act passed by the Liberal government in 1913. The act allowed all imprisoned suffragettes made ill through hunger striking to be released temporarily, only to be re-imprisoned once they had recovered. The suffragettes renamed this “letting them go; then catching them again” policy “The Cat and Mouse Act.” Print © Museum of London, London England.

Later, the Pankhursts decided to exclude all men from the organization even though from the beginning men had supported it by working on the official newsletter, donating money, and paying the bail of arrested suffragettes. The WSPU also refused to work with men’s organizations, and Christabel, much to the indignation of the mainstream suffragist movement, declared that the resistance to women’s suffrage was a war waged by all men against women. Given the all-male membership of parliament, this pronouncement did nothing to encourage the WSPU’s cause.

First in 1912 and again in 1913, police raided WSPU headquarters and seized the organization’s funds. In 1914, all mail sent to the headquarters was seized, effectively halting any attempts to raise funds. Lack of money and the poor health of the leaders from years of repeated hunger strikes greatly weakened the organization. When World War I began in 1914, Christabel declared that the WSPU would temporarily halt its campaign of violence and focus instead on more nationalist causes. She became a strong supporter of the Order of the White Feather, an organization created to shame civilian men into enlisting in the military. Members who did not view the war as a good enough reason to abandon the fight for suffrage quit the WSPU and founded new organizations. The WSPU never took on the cause of women’s suffrage again and formally disbanded in 1917.

The Representation of the People Act passed in 1918 gave property-owning women over the age of thirty the right to vote. Although the Pankhursts publicly claimed that the actions of the WSPU led to the passage of the act, those outside the movement, especially those who had campaigned nonviolently for decades, disagreed. As the constitutional suffragist Eleanor Rathbone (1872–1946) put it, the violent actions of the WSPU and other militant organizations “came within an inch of wrecking the suffrage movement, perhaps for a generation.” This first major win for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom likely was more a result of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies’ alliance with the Labour Party and their nonviolent suffrage campaigns rather than the result of acts of arson and the planting of bombs.

Although the violent actions of the WSPU may not have done the British women’s suffrage movement any favors, in a roundabout way it helped the movement in the United States. An early WSPU member was a young American woman named Alice Paul (1885–1977). While in the United Kingdom, Paul was arrested and imprisoned many times for actions related to the WSPU and was one of the first members to endure the newly legalized force feedings. In 1910, she moved back to the United States and became a leader in the U.S. women’s suffrage movement. Although Paul thereupon campaigned for suffrage using nonviolent means, her use of organized hunger strikes among imprisoned suffragists showed the influence of the WSPU. In fact, press coverage of and subsequent public outcry over Paul’s hunger strike and force feeding helped increase public sympathy for the cause.

On August 26, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment became law, and American women received universal suffrage. British women would not receive universal suffrage until July 2, 1928, when the Equal Franchise Act became law, eighteen days after the death of Emmeline Pankhurst.

Further Resources

- Purvis, June. Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Smith, Harold L. The British Women’s Suffrage Campaign 1866–1928. 2nd ed. Harlow, England: Pearson/Longman, 2007.

- Strachey, Ray. The Cause: A Short History of the Women’s Movement in Great Britain. London: Virago, 1988.

Christina Garton is a former museum professional and the current Associate Editor of Handwoven magazine.

This article was published in The Unofficial Downton Abbey Knits, 2014.