In the nineteenth century, the old custom of adult women covering their hair found new expression as women turned to handknitting. They did so to make money, to economize on millinery, or simply for the pleasure of making. Because this era valued thrifty women devoted to home and family, and because knitting had become an acceptable pastime, Victorian manuals combined these two trends in lace patterns. Many types of headwear emerged, often with names suggesting softness and femininity.

A Variety of Head Coverings

Women’s head coverings at this time varied considerably, depending on the country, region, traditions, climate, religion, marital status, social or economic class, and fashion. In Great Britain in the second half of the nineteenth century, we find numerous possibilities for covering the head. Bonnets, from plain to elaborate, were practical for outdoor wear, while caps were normally worn indoors (although sometimes under bonnets). Caps were usually made of woven cloth and embroidered or covered with lace. Ribbons and flounces might further embellish caps. Various types of lace could also be fashioned into head coverings. Of course, how much of the head was covered and with what changed over time along with dress fashions and hairstyles. For instance, by the 1860s, fashionable ladies replaced their large bonnets with small hats perched over elaborately rolled and braided hair, yet they might need veils to protect their complexions (or their privacy).

In the same century, knitting became both popular and fashionable. Women either took up needles themselves or bought the handiwork of others. A number of factors contributed to the development and spread of knitting designs in the nineteenth century. Industrialization in the previous century brought amazing changes to the production, marketing, distribution, and use of textiles. At the same time, the expansion of transportation and the British Empire gave mills access to several sources of cotton while Merino, the softest sheep’s wool, was imported from German Saxony and then Australia and New Zealand. The mills in northern England spun soft, fine, and even cotton and wool yarns ideal for lace knitting. In the 1850s, alpaca and mohair yarns produced at Saltaire near Bradford gave knitters an even wider fiber choice. As millspun yarns began replacing handspun, knitting became more widespread and popular. All manner of head, neck, shoulder, and upper body coverings were designed, knitted, and worn.

Knitted Headpieces Come into Fashion

Knitting pattern books began appearing in the late 1830s. Lace designs were written out—never charted—and errors were fairly common. Knitting terms and abbreviations were inconsistent from author to author, so knitters had to have rather well-developed skills to work successfully from published patterns. Victorian knitters also used lace samplers as a source for designs.

As with almost every aspect of knitting, we don’t know where, when, or by whom lace knitting began. Although we tend to think of Shetland lace knitting as a centuries-old tradition, there are no examples of it earlier than the 1830s. A christening shawl dated about 1837 is the oldest cataloged piece of Shetland lace, but the quality of the work indicates that style of knitting was already well developed. From then until the early twentieth century, Shetland lace was widely marketed and very popular. The commission of an exquisite cream and red wedding veil for exhibition at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London further popularized Shetland lace. As the middle class rose during this same period, more women had the means to purchase lace from the islands.

Shetland lace shawls and veils were among the many types of garments exported from Shetland. Shawls, primarily designed to cover the upper body below the neck, could conveniently be lifted to shield the head in inclement weather. Fancier lace shawls were more decorative than protective. For social excursions—to the theater, opera, visiting, church, or weddings—shawls were supplemented with a variety of head coverings, including hoods and turbans. If we look specifically at lace coverings, we find clouds and fascinators that were generally knitted (and sometimes crocheted) as well as veils and fichus, either of woven fabric or knitted lace.

Some of these bonnets sport lacy trimming, while others appear to be made entirely of lace. John Bell, La Belle Assemblée, January 1, 1816. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.226)

Some of these bonnets sport lacy trimming, while others appear to be made entirely of lace. John Bell, La Belle Assemblée, January 1, 1816. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.226)

Veils

Veils, the oldest head covering, have been worn by women for centuries. Long made from opaque woven fabrics, in the nineteenth century they also appeared in sheer materials. Wedding veils have been imbued with various degrees of symbolism depending on the religion and culture of the couple. A knitted fine-lace wedding veil, a specialty item produced by the most skilled Shetland spinners and knitters, would most likely have been affordable only by the upper classes. However, the home knitter could produce simpler, less costly, and less time-consuming veils. In that case, the veil was more like a head scarf—rectangular but only long enough to wrap the head and neck rather than the upper torso. Because one end was concealed by the wrapping, it was plain, with perhaps a few rows of garter stitch. The exposed end might have a more solid lace motif with stockinette-stitch shapes, such as leaves, separated by yarnover bars. Most of the veil length consisted of an open, very lacy, repeated pattern.

The original instructions for the veil from Weldon’s Practical Knitter, Fifteenth Series, describe a fairly typical item of that sort. Although Weldon’s states that “the pattern is particularly elegant, and yet not at all difficult to execute,” it still required time and patience. The suggested finest Fife Lace yarn was a very fine but strong yarn used for lace knitting. Since it was knitted on 000 (1.5 mm) needles, you can imagine that the yarn was very fine. No dimensions or gauge are listed but the border has 342 stitches, reduced to 216 stitches for the lace diamond. Another veil in Weldon’s is slightly wider, using the same yarn and one size smaller needles. The width of these veils was necessary to cover the long hair piled on the head.

Fancy bonnets with beautiful lace veils clearly inspired designers through the 1930s. Isabelle De Strange, Bonnet and Veil, circa 1936. Watercolor and graphite on paper. Index of American Design, 1943.8.1097. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fancy bonnets with beautiful lace veils clearly inspired designers through the 1930s. Isabelle De Strange, Bonnet and Veil, circa 1936. Watercolor and graphite on paper. Index of American Design, 1943.8.1097. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Clouds

My favorite Victorian head covering is the cloud because the name is so evocative of the garment. It was rather a latecomer on the Victorian fashion scene, with the earliest reference in 1872. Tessa Lorant, author of Knitted Shawls and Wraps, defines a cloud as “a light, loosely knitted scarf. Both ends could be fringed, or only one end fringed and the other finished in a tassel. One end of the cloud was often worn over the head, the other slung over a shoulder.” A cloud might cover the head for outdoor wear and be wrapped as a stole when indoors. Clouds are usually rectangular, but Godey’s Lady’s Book featured a square garter-stitch “cloud” large enough to cover the head and be tied at the waist.

Several cloud patterns (none illustrated) can be found in the Weldon’s Practical Knitter series. In contrast to veils, fichus, and fascinators, a cloud is loosely knitted with larger needles and bigger yarn. Suggested needles are about sizes 5 to 7 (3.75–4.5 mm).

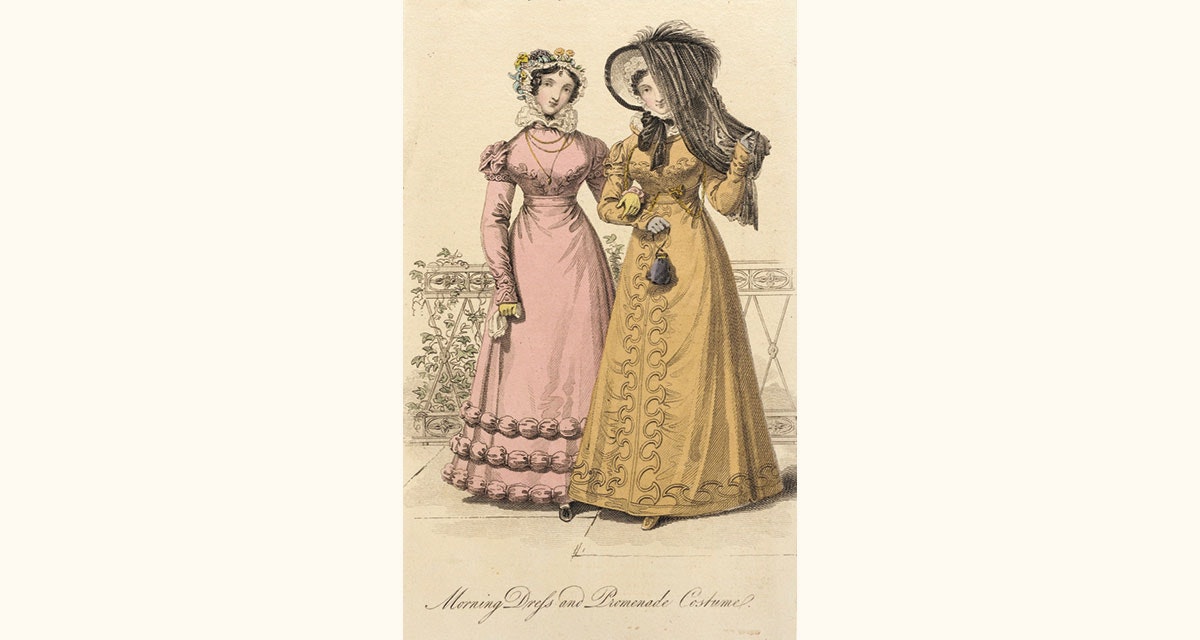

Morning dress, worn at home, required some sort of head covering; here it’s a lacy one that tucks into the collar. For walks outdoors, the lady wears a larger hat with veil. John Bell, La Belle Assemblée, Morning Dress and Promenade Costume, December 31, 1822. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.342)

Morning dress, worn at home, required some sort of head covering; here it’s a lacy one that tucks into the collar. For walks outdoors, the lady wears a larger hat with veil. John Bell, La Belle Assemblée, Morning Dress and Promenade Costume, December 31, 1822. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.342)

The openwork of the cloud is often achieved through dropped stitches or alternating fine light yarn (usually wool but sometimes silk) with big and lofty wool yarn. The differences in yarn size might be further emphasized with color stripes. One example lightens the cloud with three rows of garter stitch followed by a fourth row made by twisting the yarn three times around the needle before bringing the yarn through the stitch. The extra wraps are knitted as one on the following row. Crossed drop stitches form the center section of another cloud that has “puffed” or bobble stitch sections on each end to make the scarf very cloudlike. One “Canadian Cloud” is knitted in garter stitch and, on the last row, every fifth stitch is dropped down to the first row. That pattern explains that “a cloud is generally 1¾ to 2 yards long.” A second “Canadian Cloud” design, worked with a very basic lace pattern, suggests a 2-yard length, or long enough “to go twice round the neck and once over the head.”

Recommended colors for a cloud were white or white and pink or blue. Black and gray formed a popular color combination, and one design suggests fawn and dull red coral as “uncommon and not unpleasing.”

A bereaved woman could go out in public but needed a head covering to hide her tears. “The head-dress consists of a carmelite veil of white net, bordered with black bugles or steel, and finished with correspondent tassels.” Ackermann’s Repository, Evening Mourning Dress, December, 1810. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.87)

A bereaved woman could go out in public but needed a head covering to hide her tears. “The head-dress consists of a carmelite veil of white net, bordered with black bugles or steel, and finished with correspondent tassels.” Ackermann’s Repository, Evening Mourning Dress, December, 1810. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.87)

Fichus and Fascinators

A fichu is described by Lorant as “a triangular piece of light fabric, worn by ladies as a covering for the neck, throat, shoulders and sometimes the head.” A fascinator is a light, soft head covering gathered in with tassels at both ends. Either of these coverings might be made from any type of fabric: woven, lace, netting, knitted, or crocheted. Knitted versions were made with lace- or fingering-weight yarn and large needles relative to yarn size (about 4 to 8 [3.5–5 mm]).

A knitted or crocheted fichu tended to be rather small and to hang loosely over the shoulders as a small shawl. A fascinator, which may have developed from the cloud, was originally like a small hood: a thin rectangle covering the head and tied with ribbon at the neck. Fascinators eventually evolved into a heavier hood style covering the head, neck, and shoulders. They disappeared from fashion in the 1930s, and the name is now used to describe a very small hat topped by a fanciful “structure.”

At a ball, a woman might wish to cover her head with “a large transparent Mechlin veil, thrown occasionally over the head, shading the bosom in front, and falling in graceful drapery beneath.” Ackermann’s Repository, Ball Dress, February, 1814. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.167)

At a ball, a woman might wish to cover her head with “a large transparent Mechlin veil, thrown occasionally over the head, shading the bosom in front, and falling in graceful drapery beneath.” Ackermann’s Repository, Ball Dress, February, 1814. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner (M.86.266.167)

The pattern for one fascinator described in Weldon’s is similar to that of a cloud. It is knitted in a welt pattern, with horizontal color stripes, and finished with every fourth stitch dropped down to the cast-on row. A garter-stitch opera hood of about the same period covers the head and neck, its openness and lightness emphasized by Ostrich yarn (a silky yarn that forms natural rings).

More than a century after Queen Victoria’s death, lace knitting, shawls, and scarves remain very trendy. The purpose, colors, and significance may be quite different now, but many fashionable lace head coverings of the nineteenth century are just as stylish and wearable today.

Lace helped women dress to impress at the opera. “Head-dress, a gold net caul, inclosing the hair behind, and finished in front with a Mechlin veil of uncommon delicacy, disposed in graceful negligence, so as to display the hair on the forehead, and falling over the left shoulder.” Ackermann’s Repository, July, 1809. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Charles LeMaire (M.83.161.149)

Lace helped women dress to impress at the opera. “Head-dress, a gold net caul, inclosing the hair behind, and finished in front with a Mechlin veil of uncommon delicacy, disposed in graceful negligence, so as to display the hair on the forehead, and falling over the left shoulder.” Ackermann’s Repository, July, 1809. Hand-colored engraving on paper. Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California. Gift of Charles LeMaire (M.83.161.149)

This article was originally published in Knitting Traditions Spring 2016.

Resources

- Bennett, Helen. Scottish Knitting (Shire Album 164). Aylesbury, United Kingdom: Shire Publications, 1986.

- Don, Sarah. The Art of Shetland Lace. London: Mills & Boon, 1980.

- Jurgrau, Andrea. New Vintage Lace: Knits Inspired by the Past. Fort Collins, Colorado: Interweave, 2014.

- Laurenson, Sarah, ed. Shetland Textiles: 800 BC to the Present. Lerwick, Shetland: Shetland Heritage Publications, 2013.

- Lorant, Tessa. Knitted Shawls and Wraps. Wells, Somerset, United Kingdom: Thorn, 1984.

- Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave, 1987.

- Weldon’s Practical Needlework, vols. 1–12. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave, 1999–2005.

Carol Huebscher Rhoades of Madison, Wisconsin, has a doctorate in comparative literature, specializing in nineteenth-century British and Swedish women’s writing. She teaches workshops on traditional British and Scandinavian knitting and crochet and translates Scandinavian knitting and crochet books and cookbooks into English.

Originally published February 17, 2020; updated October 14, 2022.