My nursemaid Virginia taught me my first stitches when I was five as we sat on a bench in the Plaza Olivos on sultry summer afternoons in suburban Buenos Aires in 1941. When I was about nine, I even won a prize for an embroidered square that I had entered in the annual St. Dunstan’s Exhibition of Needlework. I remember giving it later to an uncle as a “razor-wiper-offer,” much to the amusement of the adults in my family.

After that, I forgot about needlework until I was diagnosed with cancer in 1999. Since then, I’ve turned out well over a hundred pieces of embroidery. I’d venture to say that needlework has restored me to health as much as chemotherapy has.

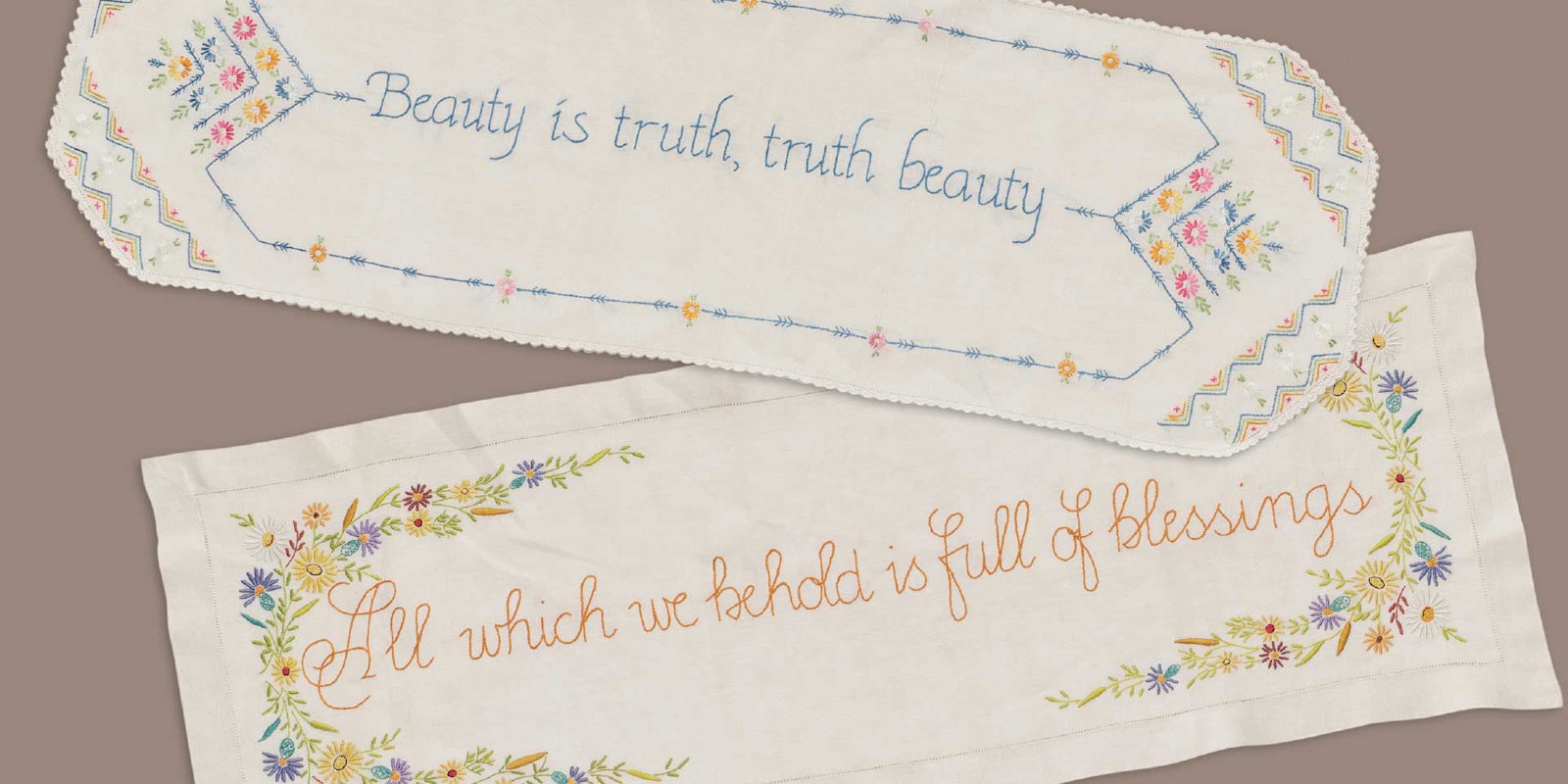

My needlework is “shared” with the hands of women of long ago. I buy vintage dresser scarves and doilies at fairs and flea markets for $10 to $20 and then embroider snatches of poetry or song on them. I look for antique linen with old lace and with borders filled with embroidered flowers, ribbons, robins, baskets, or butterflies. The feeling that I’m creating something new out of something old adds to my pleasure and satisfaction.

I try to match the words or quotation with the personality or circumstances of the person for which the piece is intended. My friends and family are very appreciative of such gifts because I have given my projects a fair amount of thought.

I embroidered the phrase “L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux” (“What is essential is invisible to the eye”) on a runner for a niece whose favorite book is The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Since she majored in French in college, I rendered the line in Saint-Exupéry’s original French.

Embroidery by the author.

Embroidery by the author.

My brother has a banner that he claims he flies from the water tower of our old farm in Argentina. On it, I embroidered the words “Sic transit gloria mundi (“Thus passes the glory of the world”), a saying that we remember my father repeating almost every day of his life (sometimes he just said, “Sic”).

“If music be the food of love, play on,” the opening line of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, decorates a runner that my musician son Dylan uses to cover his keyboard. For another son, who lives in a house on pilings above Grassy Sound, in southern New Jersey, I embroidered a runner with “Though the seas threaten, they are merciful,” a line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

I use stem stitch for most lettering, but chain stitch and cross-stitch also may be used. Capital letters are marvelously enhanced with French knots, satin stitch, straight stitch, and lazy daisy stitch. The number of strands of thread is dictated by the thread count of the linen. Occasionally, I add embroidered flower motifs or borders. I always try to make the new blend in with the old.

My renewed interest in doing needlework and the benefits I’ve reaped from it puts me in agreement with the many psychologists who maintain that manual work such as embroidery has great healing power. Doing it also has made me think about my favorite lines in poetry in ways that are deeper and thus more satisfying than merely rereading them would be. But best of all, needlework has created a web of well-being with silk threads, poetry, memories, and friendship fostered between me and the recipients of the embroideries.

Interested in more embroideries? This article and others can be found in the July/August 2002 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including July/August 2002. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Jehane Flint Taylor retired from a career in education in this country and abroad, and she was a part-time interpreter at the Emlen Physick Estate, a Victorian-house museum in Cape May, New Jersey.

Originally published March 15, 2021; updated May 22, 2024.