In 1877, S. Annie Frost introduced her book The Ladies’ Guide to Needle Work, Embroidery, etc. with these words: “There is no occupation so essentially feminine, at the same time so truly ladylike, as needlework in every branch, from the plain, useful sewing that keeps household and person neat and orderly, to the exquisite, dainty fancy work that adds beauty to every room.” She was echoing sentiments found in other publications of the century, including Godey’s Lady’s Book, of which she was soon to assume control with the January 1, 1878, edition. Sewing had, for many centuries, been divided into two categories: the necessary and the decorative.

But in the nineteenth century, the sewing machine and other technological advances replaced the need to hand sew the family clothing, bed linens, and other textiles. Still, middle- and upper-class women in America considered the needle arts, plain and fancy, to be an obligatory part of their responsibilities as wives, mothers, and homemakers. The samplers of the previous generations, demonstrating a schoolgirl’s sewing abilities—often with alphabets, numerals, and moral poetry—were replaced by a wide variety of fancy-work projects including Berlin work, crocheted and knitted garments, and even theorem painting, offered in mass-produced magazines and books. But alongside these more fortunate women, others sewed to survive and support their family. “The Trials of a Needlewoman,” by T. S. Arthur (1809–1885) and serialized in Godey’s 1854 editions, begins “Needlework, at best, yields but a small return. Yet how many thousands have no other resource in life, no other barrier thrown up between them and starvation!”

Seamstresses sewed up the gowns designed and cut by a well-paid dressmaker. Women worked at home sewing gloves or making buttons as part of large cottage industries. Buttonhole samplers reveal a combination of reasons for taking up needle and thread, where usefulness combines with imagination to produce something more. As Rozsika Parker wrote in The Subversive Stitch, “The situation of embroidery is more elusive. When women paint, their work is categorised [sic] as homogenously feminine—but it is acknowledged to be art. When women embroider, it is seen not as art, but entirely as the expression of femininity. And crucially, it is categorised as craft.” Today we might discuss the question of whether buttonhole samplers, or their more-numerous cousins the darning samplers, could be described as art, folk art, or craft.

Detail of sampler inscribed “KM12” and “KM18” with a variety of buttonholes and other sewing techniques. Sewing Sampler (USA) (1957-180-37), early nineteenth century; cotton; H × W: 13 × 69 cm (51⁄8 × 273⁄16 in.); Gift of the estate of Mrs. Lathrop Colgate Harper; 1957-180-37. Photo by Smithsonian Design Museum

Buttons and Buttonholes

Before there could be buttonhole samplers there had to be buttonholes—and the buttons to fit through them. The oldest button discovered is thought to be roughly 5,000 years old. Made of shell, it was found in what is now Pakistan.

Buttons probably were ornamental before they became practical. Exquisite buttons made from many different materials can be found in numerous museum collections. Only the wealthy could afford the richly ornamented buttons, which were often made from costly materials, on their fashionable dress.

Clothing historians agree that buttons with buttonholes started to be used around the thirteenth century, a time when European clothing began to conform to the contours of the body. Buttonholes developed to replace the loops previously used to close garments.

The use of buttons and buttonholes grew through the centuries, beginning with men’s clothing. As time passed, changes in technology meant that more buttons could be made from cheaper materials. Wood, bone, and the precious metals and gems from which buttons had been made began to fade from common use. The cultural and technological changes spurred by the Industrial Revolution contributed to the production of the inexpensive, mechanically produced metal buttons now seen on many Victorian garments. The growth of the middle class and other social, economic, and political issues all affected clothing styles. Buttons became indispensable: they make garments fit, close smoothly and stay closed, and can be decorative as well as functional.

Detail of sampler embroidered with buttonholes, overcasting over deflected element, and cross-stitches. The initials “M.N.” (not shown) and date are sewn in red floss. Sewing Sampler, no country of origin, 1824; cotton, silk; 16.5 × 33.7 cm (6½ × 13¼ in.); Bequest of Gertrude M. Oppenheimer; 1981-28-201. Photo by Smithsonian Design Museum

Buttonhole Samplers

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), which has more than 700 needlework samplers, the origin of our word “sampler” is from the old French essamplaire or Latin exemplum, both meaning an example. In one of their feature articles on the V&A website, they say, “Before the introduction of printed designs, embroiderers and lacemakers needed a way to record and reference different designs, stitches and effects.” The band style of early samplers from the 1600s, long and narrow in shape, suggests that the housewife or seamstress embroidered a line of alphabet, fancy stitching, or designs as if she added a line to a poem.

Buttonhole samplers don’t contain the elegant scenes, alphabets, and pious poetry found in young girls’ fancy sewing, now called schoolgirl samplers. A young woman preparing for a job as a domestic servant or seamstress could use a buttonhole sampler as a résumé, demonstrating her sewing abilities.

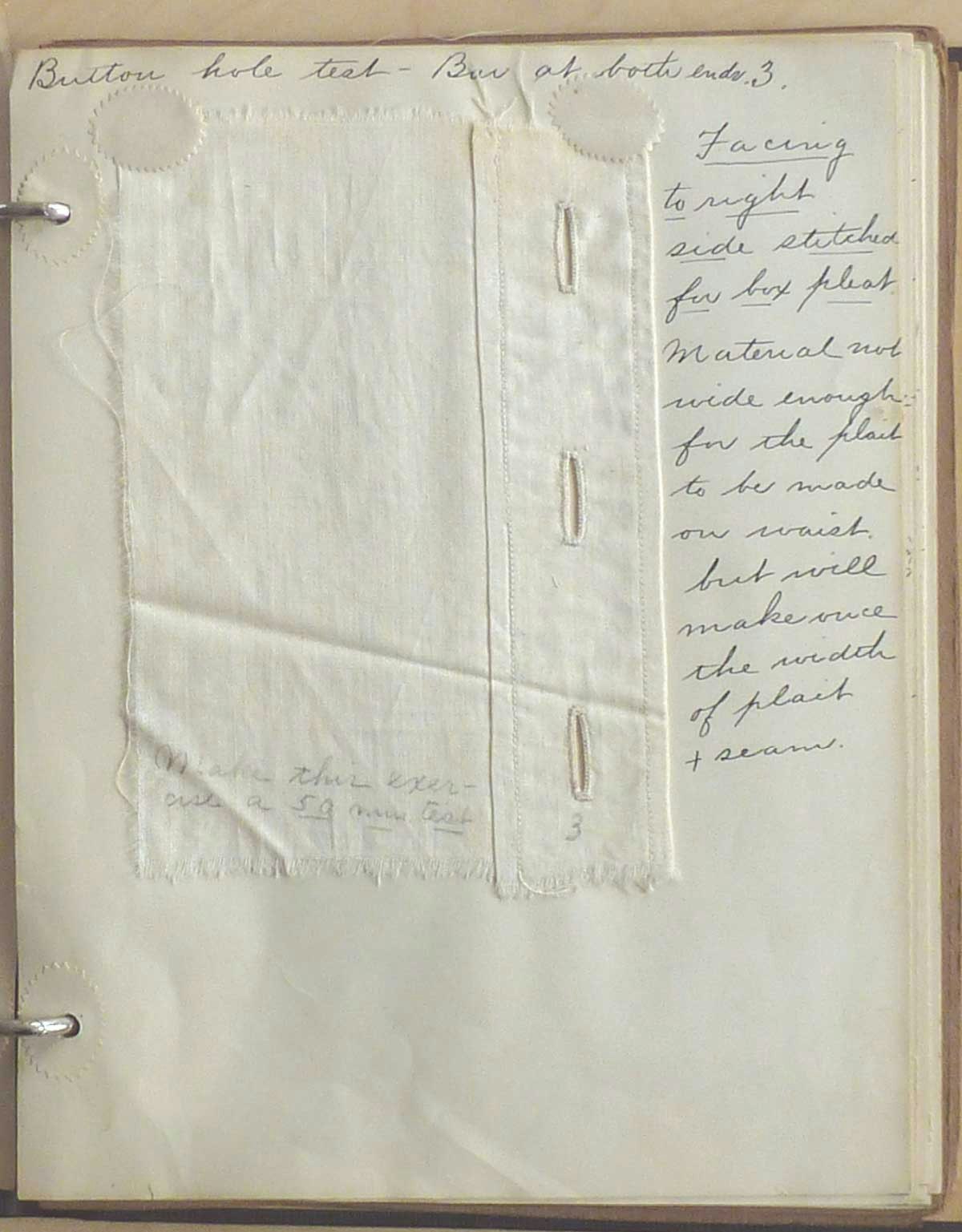

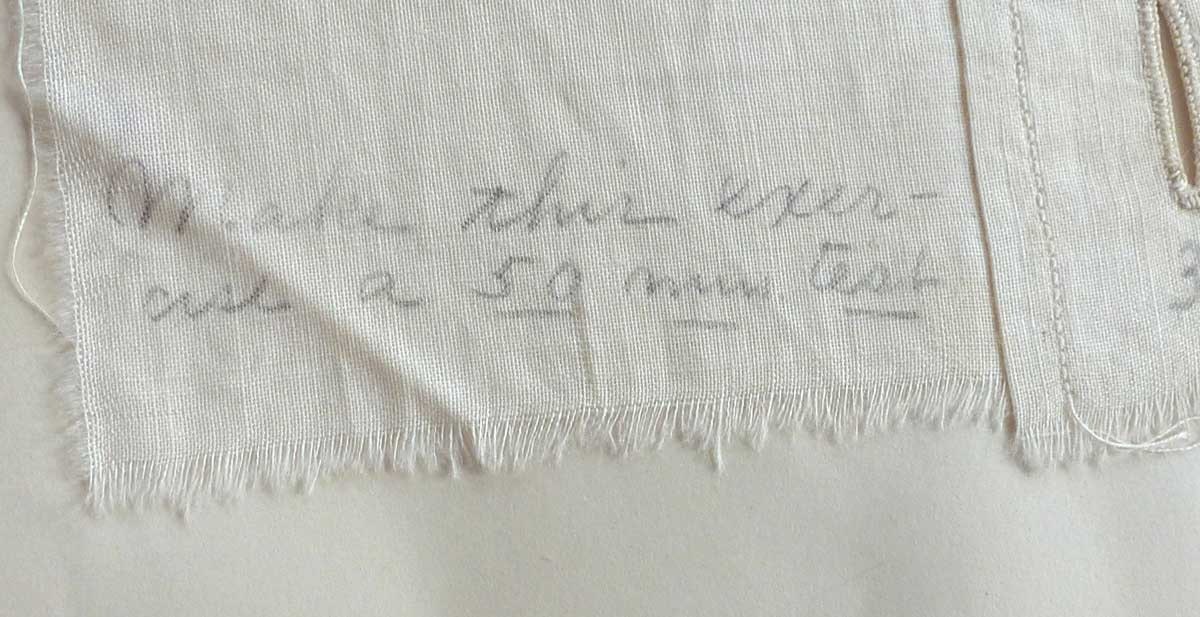

The Historic Textile and Costume Collection at the University of Rhode Island holds a series of small notebooks that contain sewing exercises made between 1907 and 1919, most complied by Lucy H. Pierce. She taught at the Technical High School in Providence, Rhode Island, after 1909. This sample (URI 1950.01.103) requiring a student to handsew three buttonholes includes, “Make this exercise a 50 minute test.” By 1920, Lucy was the director of the Rhode Island Household Arts Teachers’ Association. Photo by Susan J. Jerome

Today, one finds few examples of buttonhole samplers in museum collections. These utilitarian textiles weren’t saved and proudly displayed as the schoolgirl samplers were. Buttonhole samplers accessible online include six at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. These all date from the nineteenth century, with three identified as European, two with unknown origins, and only one from the United States. A small sampler from England has ten highly decorative, white silk buttonholes surrounding “MJ 1846” worked in red silk. The linen ground measures only about 7½ inches (19 cm) square. (Accession number 2008-31-9, Object ID 18727649)

The collection at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) includes a similar buttonhole sampler dated 1832 and identified as German. This small linen square (5 × 5¼ inches [12.7 × 13.3 cm]) displays twelve white buttonholes, each decorated with designs in drawnwork, chain stitch, French knots, and other sewing around the slit that has been finished with the buttonhole stitch. The maker included her initial, date, and a crest also worked in red. (Accession #1980.62.2) These two buttonhole samplers are examples of the “plain, useful sewing” being combined with the “dainty, fancy work” described by Miss Frost in 1877.

The American sampler at FAMSF, categorized as a sewing sampler, contains a variety of sewing techniques including buttonholes, hem stitches, tabs, knot stitches, hooks and eyes, button sewing, and needle-lace fillings. It is definitely sewing made to keep “household and person neat and orderly.” The maker embroidered “KM18” and “KM12” at either end, suggesting that the work was completed in 1812. Like the earliest dated samplers, this one measures 51⁄8 × 271⁄8 inches (13 × 68.9 cm). Ten buttonholes run along the bottom. (Accession number 1957-180-37, Object ID 18417895)

Examples of buttonholes combined with a variety of sewing techniques appear on textiles that functioned as exercises for those learning to sew. Public schools became well established in the nineteenth century, and by the turn into the twentieth century, part of the curriculum included home economics, cooking, and sewing. In June 1905, Miss Ida Blandin, in a column in Bloomington, Illinois’s The Weekly Pantagraph, described her work in an Illinois school district that included teaching “sewing sampler work…. Pupils made samplers by hand in school which show all the different kinds of stitches and sewing used.” Interestingly, Miss Blandin taught both girls and boys these basic sewing skills.

The Historic Textile and Costume Collection at the University of Rhode Island has a number of sewing- sample books. Glued or taped to each page is a sample of a sewing technique, sometimes finished as a miniature pair of lady’s drawers or a waistband. Here, too, we find examples of a student’s efforts to make the perfect buttonhole by hand.

Detail of the notebook sample (URI 1950.01.103) on opposite page. Photo by Susan J. Jerome

Automating Buttonholes

The first American sewing machine to stitch a buttonhole was patented in 1854 by Charles Miller of St. Louis, Missouri. (Patent No. 10609 issued March 7, 1854) Others, such as Henry Alonzo House (1840–1930), worked to perfect an automatic buttonhole machine. By the time I took mandatory home economics (for girls only) in middle school in the late 1960s, handsewing was limited to hem stitches and button sewing. No fancy sewing. No samplers. The buttonholes were made on a machine with an attachment. Now, if you are lucky, a few clicks on a computer will sew the perfect buttonhole every time.

Resources

- Arthur, T. S. “The Trials of a Needlewoman.” Serialized in Godey’s Lady’s Book, Philadelphia, 1854.

- Bolton, Ethel Stanwood, and Eva Johnston Coe. American Samplers. Princeton, New Jersey: The Pyne Press, 1973. Unabridged reprint of material published by The Massachusetts Society of The Colonial Dames, 1921.

- Edmonds, Mary Jaene. Samplers & Samplermakers. An American Schoolgirl Art 1700–1850. New York: Rizzoli and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991.

- “Embroidery—a history of needlework samplers.” Victoria and Albert Museum. www.vam.ac.uk

- Frost, S. Annie. The Ladies’ Guide to Needle Work, Embroidery, etc. New York: Henry T. Williams, 1877.

- Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch. Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. New York: Routledge, 1989.

- Schoelwer, Susan P. Connecticut Needlework. Women, Art, and Family, 1740–1840. Middletown and Hartford, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press and The Connecticut Historical Society, 2010.

- Swan, Susan Burrows. Plain & Fancy. American Women and Their Needlework, 1700–1850. New York: A Rutledge Book/Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977.

Susan J. Jerome is collections manager at the University of Rhode Island Historic Textile and Costume Collection. She earned her MS degree from the University of Rhode Island, Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design. Prior to continuing her education, she worked for a number of years at Mystic Seaport Museum. She lectures on topics of fashion history and needlecraft; works as a textile and quilt conservator; and is a consultant to museums and historical societies. An avid textile-enthusiast, she is happiest when writing, talking, and doing all things textile.

This article was published in the Summer 2020 issue of PieceWork.