More than 65 years ago, my grandmother sat in her room at Colby College, a small liberal-arts school tucked into the middle of Maine. Curling her feet beneath a wide skirt, Kathy used the light from a nearby window to wind yarn for a special project, its browns and tans matching the bricks of her dorm.

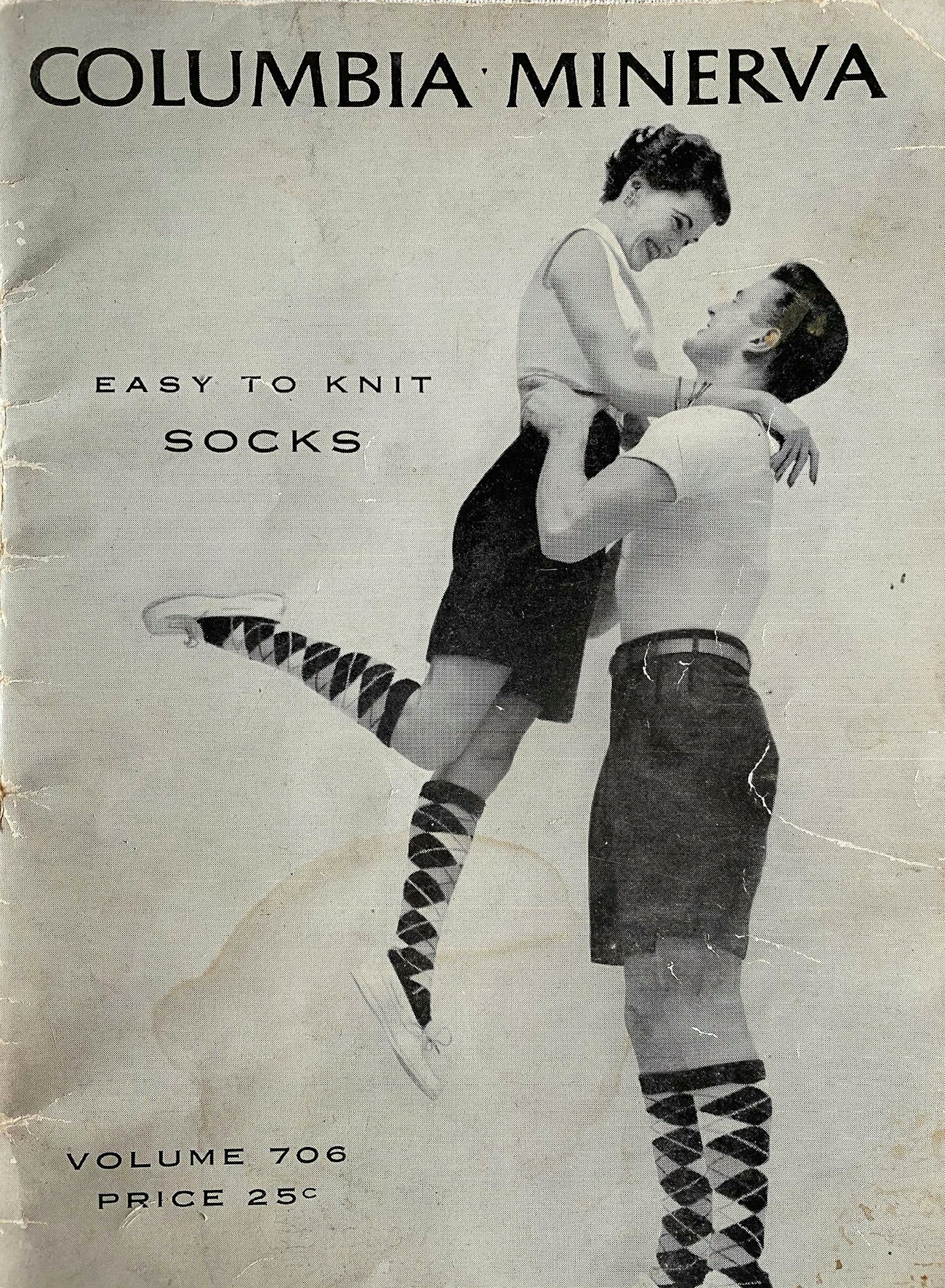

A native of Ohio, Kathy bucked tradition to attend classes halfway across the country, only returning home a few times a year. As she sat missing her family, she opened up a Columbia Minerva Easy to Knit Socks pattern book to a diamond argyle pattern and cast on 68 stitches to make a special pair of socks for her father.

Later, in both a new century and a new millennium, I flip through the pages of Kathy’s 1955 pattern book—the exact copy that Kathy held in her hands when she was not too much younger than me. My Grandma Kathy still has the pair of socks she knitted for her father, and I wear them when I visit her in Maine. I think of her argyle socks, as well as the longer history of argyle patterns, as I wind yarn to knit my own warm, colorful socks.

Argyle or Argyll?

Argyll, or Earra-Ghàidheal in modern Gaelic, is a historic county in Scotland full of history, with strong connections to Clan Campbell. It’s from this powerful highland clan’s woven tartan that the argyle pattern of today evolved. Argyle is defined by the Scottish Tartans Authority as a “pattern designed to imitate a tartan.” The repeating diamonds that make up argyle patterns are the familiar squares created by stripes in the warp and weft of most tartans turned 45 degrees. Before socks and stockings were knitted, woven fabric cut on the bias could provide a fairly stretchy option for leg-conforming textiles, turning blocks into diamonds. However, the squares and stripes easily produced in woven fabric can be quite challenging to reproduce in a knitted stocking. Interestingly, the Scottish Tartans Authority goes on to state, “Argyle hose are a simplified version of tartan hose in cases where the pattern is too intricate to replicate exactly. It became more usual (and sometimes more pleasing to the eye) if the tartan design was imitated but not copied exactly.”

Photograph of an “Officer of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders Reading to the Troops, Edinburgh Castle” by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, April 9, 1846. (1997.382.25). Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Knitting surged in popularity during World War II, as both women and men on the home front crafted warm items for soldiers abroad. Even after the war, knitting remained a ubiquitous pastime. As Susan M. Strawn explains in Knitting America, “Men who liked the handknit sweaters and socks they received during the war often wanted their wives to keep knitting for them.” She continues, “Nearly every postwar knitting book included an argyle pattern.” Argyle patterns were so sought after that Strawn calls the diamonds a national craze.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, knitted items remained cheaper than their store-bought counterparts, especially during shortages of clothes after the war. One company advertising a knitting kit claimed that crafters could create a pair of socks for themselves at only one-fifth of what they would pay over the counter. Enterprising students on college campuses could sell argyle sock pairs for $10, and contests inspired hundreds of entrants.

Erika used her grandmother’s copy of Easy to Knit Socks (1955) to begin her own argyle adventure. Photo by Erika Zambello

When Grandma Kathy worked on the argyle socks in her college dorm room in 1955, both argyle and knitting were riding this wave of popularity. “Everyone was knitting,” Kathy explains. Although she learned to knit as a child, never had she tried such a complicated and multicolored pattern. She, and so many young American women like her, used bobbins and advice from dorm mates to move from the cuffs to the heel and down to the toe, working across two needles before sewing up the eventual seam.

Unlike store-bought socks, handknitted socks often stood the test of time. With careful craftmanship and wear, the socks Kathy knitted for her father warmed his feet for decades. After his death in 1981, she inherited them. The diamond socks come out every fall for walks by the ocean, snowshoeing, and skiing. Though the stitches have melded together in some places, they have never been darned or stained, looking much the same as they did the morning that Great-grandpa Gwynn pulled them on for the very first time. Borrowing the socks during my visits has become a new tradition. I never met my great-grandfather, but for a few hours, we share a simple experience: toasty feet in comfy socks.

Interested in learning more about argyles? This article and a pattern can be found in the Summer 2021 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Summer 2021. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- “Hose.” Scottish Tartans Authority, tartansauthority.com/highland-dress/modern/hose.

- Strawn, Susan M. Knitting America. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2007.

Erika Zambello is an environmental communications specialist living and working in north Florida. She is a strong proponent of knitting outside and works on her projects while walking, hiking, and exploring. Follow her adventures on Instagram @knittingzdaily.

Originally published August 2, 2021; updated September 2, 2024.