In India, quilts are an intrinsic part of life and celebrations, but rarely are they documented. Rarer still is documentation or celebration of the quilters. The usual reply one hears when asking about a quilt in India is that “it is made by women, and it is there in the house.” These everyday textiles are overlooked because other richer fabrics, textiles, and embroideries hog the limelight. Thus, one seeking to learn more has to ferret out information regarding quilts and quilters from traveling craftsmen.

The women who make quilts for their homes, as dowries and for gifting, make them with a lot of love and affection, embroidering carefully. The quilts are excellent examples of recycling and reuse. Most quilts are made with layers of old sarees, dhotis, or other clothes with an outside layer of new cloth. To make up for the reused, worn-out cloth, the surface of the quilt is embroidered attractively. The embroidery also adds a personal touch to the quilt, something made lovingly by the mother or grandmother. In this Indian textile genre are kantha—now a buzzword the world over—sujni, Dhadki, Godhari, and Kutchi quilts.

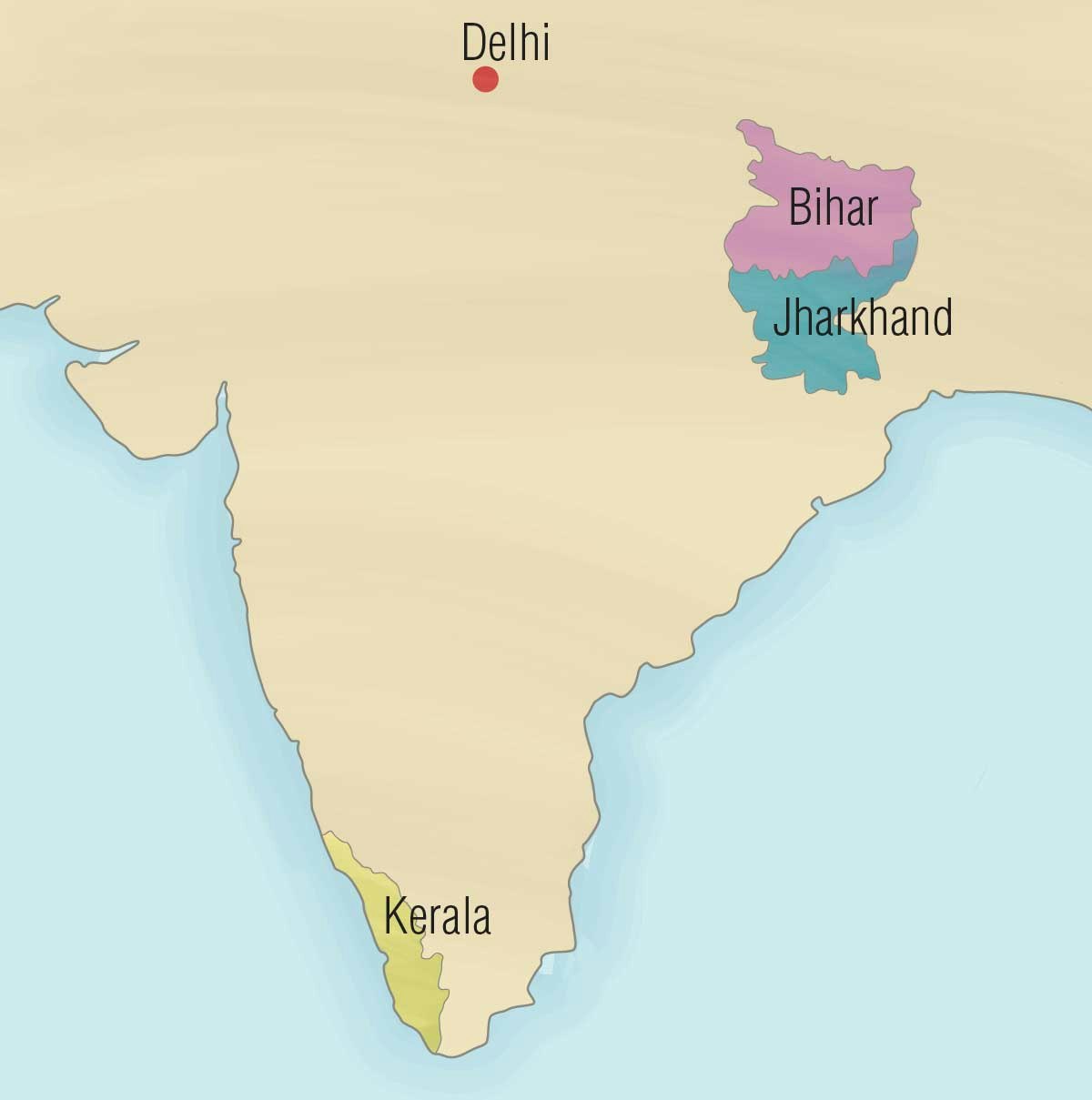

Quilts have an ancient history in India. Anamika Pathak, an authority on textiles and former Curator of Decorative Arts Section at the National Museum, New Delhi, writes in Embroidering Futures: Repurposing the Kantha that the word kantha originated from the word kathina, meaning hard or difficult to find. It referred to the cotton cloth given by devotees to Buddhist monks. She goes on to describe how Lord Buddha asked his favorite disciple, Ananda, to make a robe that resembled the rice fields of Magadha (a location in the Ancient Kingdom, sixth to fourth century BCE, near present-day Bihar). Ananda sewed patches of cloth together, creating a ripple-like effect, and thus the kantha took shape.

Chitra met Mallo and her fellow artists when they traveled from Jharkhand to Delhi. Illustration by Ann Sabin Swanson

Chitra met Mallo and her fellow artists when they traveled from Jharkhand to Delhi. Illustration by Ann Sabin Swanson

Old Cloth, New Life

As I was researching an article for PieceWork about sujni quilts in 2007 (see link below), I found many women from Bihar willing to make sujni and talk about their work. Then in December 2010, my mother, K. S. Jayalakshmy, passed away suddenly. Apart from the void, I was left with a lot of the cotton sarees that she wore. Like many Indian women, my mother wore only sarees. She was a lover of handlooms (handwoven cloth), especially cottons.

Almost two years after her death, I had the guts to try to sort out her sarees. The sarees brought back memories. But more importantly, there was a story to each saree, and I had been a part of most of them—a sale we had gone to or a seller we had haggled with. These were everyday-wear cotton sarees, which usually end up being torn, cut into pieces, and used as polishing cloths at wholesale markets. It seemed a crime to give my mother’s sarees to the dump.

A saree is a gorgeous, 45-inch (114 cm) wide, 6-yard (549 cm) length of cloth with fine borders that ends in a half yard (46 cm) of ornamented edging called the pallav (also called a pallu when speaking). Saree fabric is never torn by women. In fact, my mother would give away old sarees whole, never letting me tear off and save the border or pallav.

Finding myself with a stack of old, precious sarees, I began my journey to find someone who could make sujni quilts with them. A lot had changed in six intervening years, and I found no one in Bihar interested in making sujni quilts. Several artisans had settled in Delhi who, again, were not keen to making these traditional textiles. Quilts take up space, which is scarce in cities; painting is faster and paid instantly. They were happier making traditional Madhubani paintings, which provided the original inspiration for the motifs found in sujni quilts. These paintings were now more popular in the area as they earned better profits. To encourage women to continue quilting, I started buying the quilts they had already made. In the process, my collection of more than 25 sujni quilts developed.

It was against this backdrop that I heard of another genre of quilts called ledra from the Indian state of Jharkhand. Research led me to quilts from the town of Hazaribagh in Jharkhand. There, I touched base with Bullu Imam, who is credited with bringing world-wide attention and conservation efforts to the famous Sohrai and Khovar paintings from this area. The artform continues today in tribal communities, and its motifs are related to the prehistoric rock art found in the region. Bullu Imam asked me to get in touch with his son Justin Imam who was coming to Delhi to organize an exhibition of the paintings. Justin faithfully carried a couple of quilts for me to see.

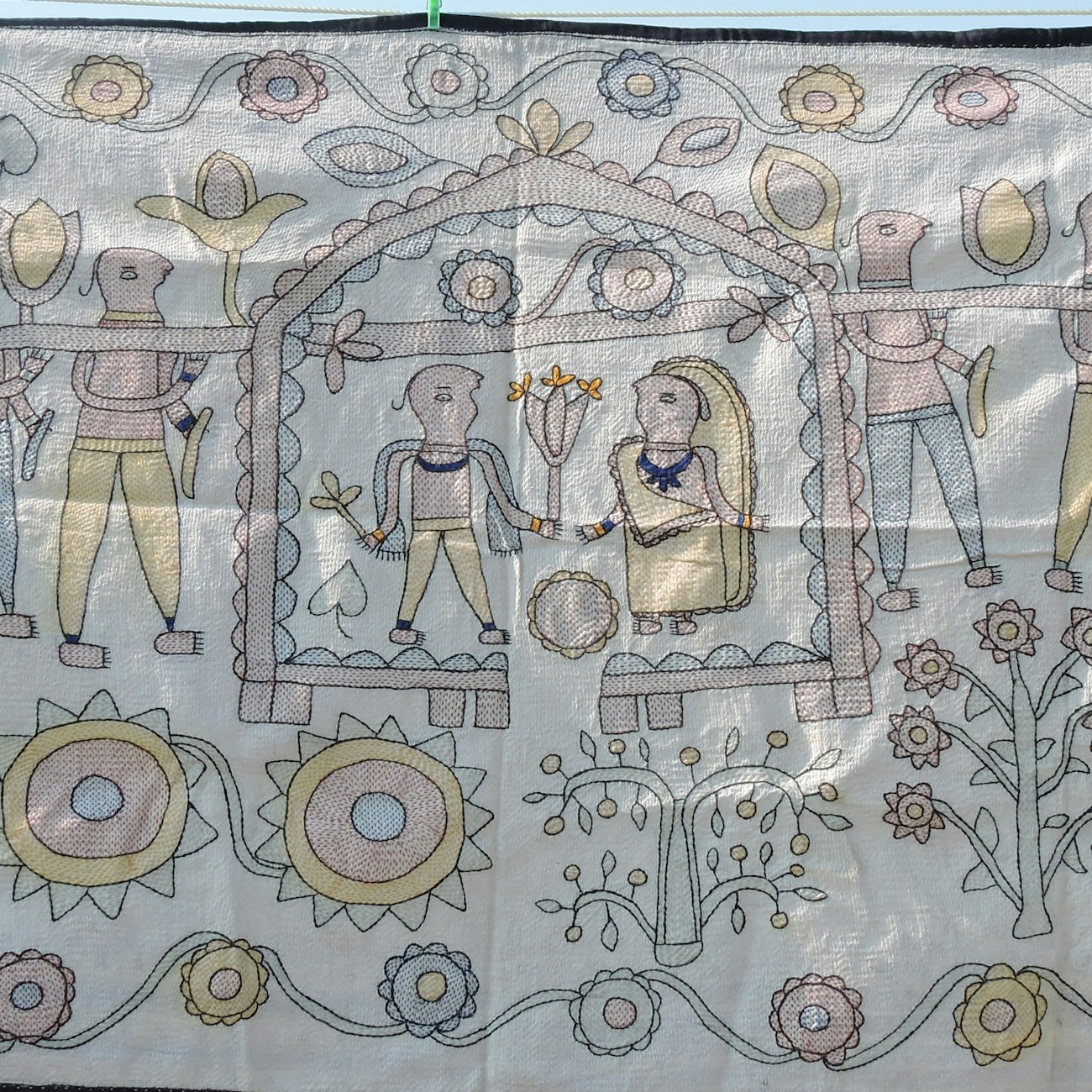

Details of Chitra’s ledra.

Details of Chitra’s ledra.

The Ledra Quilts

The ledra quilts take their inspiration from the Sohrai and Khovar paintings, and the motifs stitched into the quilts are similar to those of the paintings. The motifs include playful deer, bees whizzing around, flowers, squirrels, peacocks, parrots, dancing peacocks, fish, and tortoises. Each of these motifs is rich in symbolism and has its own narrative.

I met Justin at the painting exhibition in June of 2018, and I had also hoped to meet the women, who were joining the exhibit of their work and doing demonstrations. The three are from different tribes and paint as well as make ledra for home and personal use. The paintings displayed were gorgeous, but the women had gone away to do their shopping. Justin was embarrassed, and I promised to try to meet them the next day. Sensing his embarrassment, I took my chances in asking him to help me get a ledra quilt made from my mother’s sarees; he agreed.

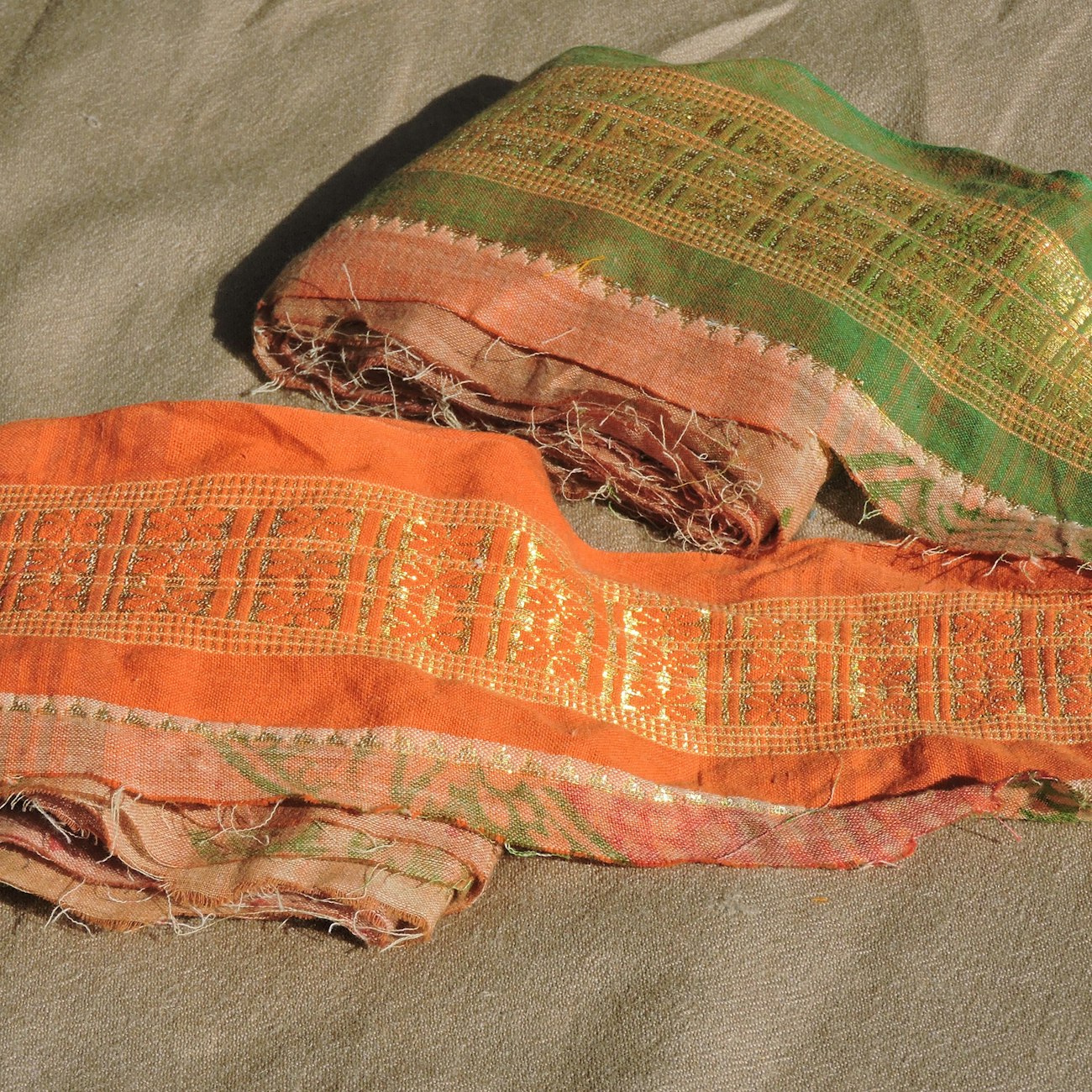

On my trip the next day, I carried two sarees from my mother’s saree bundle. One was a fawn color with deep red borders and pallav; this had been a gift for my cousin’s wedding. With no one to stop me, I tore off the pallav and border. Later, the neighborhood tailor transformed this pallav into a blouse for me. The border is still here, waiting to be reused.

My mother purchased the second saree on her trip to Kerala; it had a Ganga Jamuna border, which means that the border had different colors at the top and bottom. These two-color borders in India are named after the two holy rivers. I removed the borders hoping to use them for something else. I gave the two sarees to Justin.

I finally met the women—Mallo, Parboti, and Putli—and after much prodding, they started telling me about the ledras of Hazaribagh. They were actually quite taken aback that someone could be curious about an everyday quilt made with old sarees. The women sang songs associated with ledra-making, a daughter-in-law spoke of instruction given by her mother-in-law, and so on.

The area around Hazaribagh has 10 or 11 tribal communities, which include Oraon, Munda, Santhal, Prajapati, and Khurmi. Each community has a tradition of making quilts. What distinguishes the different quilt traditions is the stylization and drawing of the motifs that are stitched onto the surface. Justin is a pro at differentiating the quilts and naming the community associated with each one.

Chitra removed the borders from her mother’s sarees before the bodies of the sarees were made into ledra quilts.

Chitra removed the borders from her mother’s sarees before the bodies of the sarees were made into ledra quilts.

Making of Ledra Quilts

Ledra dhaga, or threads, are available in the market in six colors. To begin a ledra, the threads are purchased, the women place sarees together, and then they draw the motifs. Fresh-cut raw turmeric is used to draw the motifs. The raw turmeric creates a nice yellow mark that can be washed away easily.

The rich motifs make the quilts absolutely striking. The motifs capture the forest in all its entirety: animals, birds, and plants. The women embroider using four different stitches including running, chain, and two indigenous stitches called machli kanta (fishing rod) and gohar.

Unlike kantha and other quilting traditions where layers of old cloth are covered with a new cloth, ledra quilts are typically made entirely of old clothes. The exception is when they are created for marriage ceremonies and spread on the floor of the marriage chamber. Ledra created for this purpose are made using new cloth.

Connecting Threads

I had given to Justin two sarees roughly 5-1/2 yards (503 cm) in length and 42 inches (107 cm) in width. Justin took the sarees saying he would hold them dear in my mother’s memory. After much follow-up, the sarees were given to Mallo, who promptly enlisted her daughter-in-law to begin the project. She painstakingly quilted the sarees together using chain, running, and blanket stitches. Two beautiful peacocks, one dancing and the other preening, are embroidered with a host of fish. Both peacocks and fish are symbols of fertility. Justin sent me photos of the quilt being made.

The quilt, made from the sarees I entrusted to Justin in June 2018, finally arrived on November 23, 2019. The day seemed symbolic as it was my mother’s death anniversary according to the Hindu lunar calendar. It somehow seemed as if she approved of her sarees being converted into a memory quilt. What gave me further satisfaction is that the sarees that would have been dumped have been turned into a piece of art, and Mallo and her daughter-in-law were incentivized to continue making these quilts. There is much to be done with this quilting technique.

One of the vintage sujnis Chitra acquired while searching for someone to quilt her mother’s sarees. This sujni is at least seventy years old.

One of the vintage sujnis Chitra acquired while searching for someone to quilt her mother’s sarees. This sujni is at least seventy years old.

Chitra’s Sujni Quilts: Ten Years Later

After my article “Sujnis: Recycling Clothing into Quilts in India” appeared in PieceWork Sept/Oct 2007, I continued collecting sujni quilts. Though it is believed that the term sujani originated from the word sozni, or needlework, I have since found out that it is su (meaning re-) and jani (meaning born). So, sujani is one that is reborn, symbolizing the recycle or upcycle of old sarees. The thick quilts, which use four to five layers, are rarely made now. Smaller or three-layered quilts are made for market. There is revival happening everywhere; how it goes forward is anybody’s guess.

Interested in more reuse techniques? This article and others can be found in the Fall 2020 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Fall 2020. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Balasubramaniam, Chitra. "Sujnis: Recycling Clothing into Quilts in India." PieceWork September/October 2007.

- Sethi, Ritu, Ed. Embroidering Futures: Repurposing the Kantha. Bangalore: India Foundation for the Arts, 2012.

Chitra Balasubramaniam writes, collects, and experiments with textiles, and follows her passions by writing about food, travel, and heritage. She dabbles with stock-investment analysis and research. She also runs a small travel guide at visitors2delhi.com. Find her on Instagram as @visitors2delhi.

Originally published December 9, 2020; updated April 2, 2025.