The original American states along the eastern seaboard are about 8,000 miles from India, but this distance didn’t stop an American girl from stitching a sampler about an injustice in India in the early nineteenth century. In 1813, Hannah Powell worked a large (25 5⁄8 × 19 5⁄8 inches) embroidered petition against execution, recounting a traumatic tale from an Indian woman victimized by British India’s first governor-general.

Although the embroidered document, now in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), is a mystery, delving deeper into its origins tells us much about the early American republic and the girl who stitched the sampler.

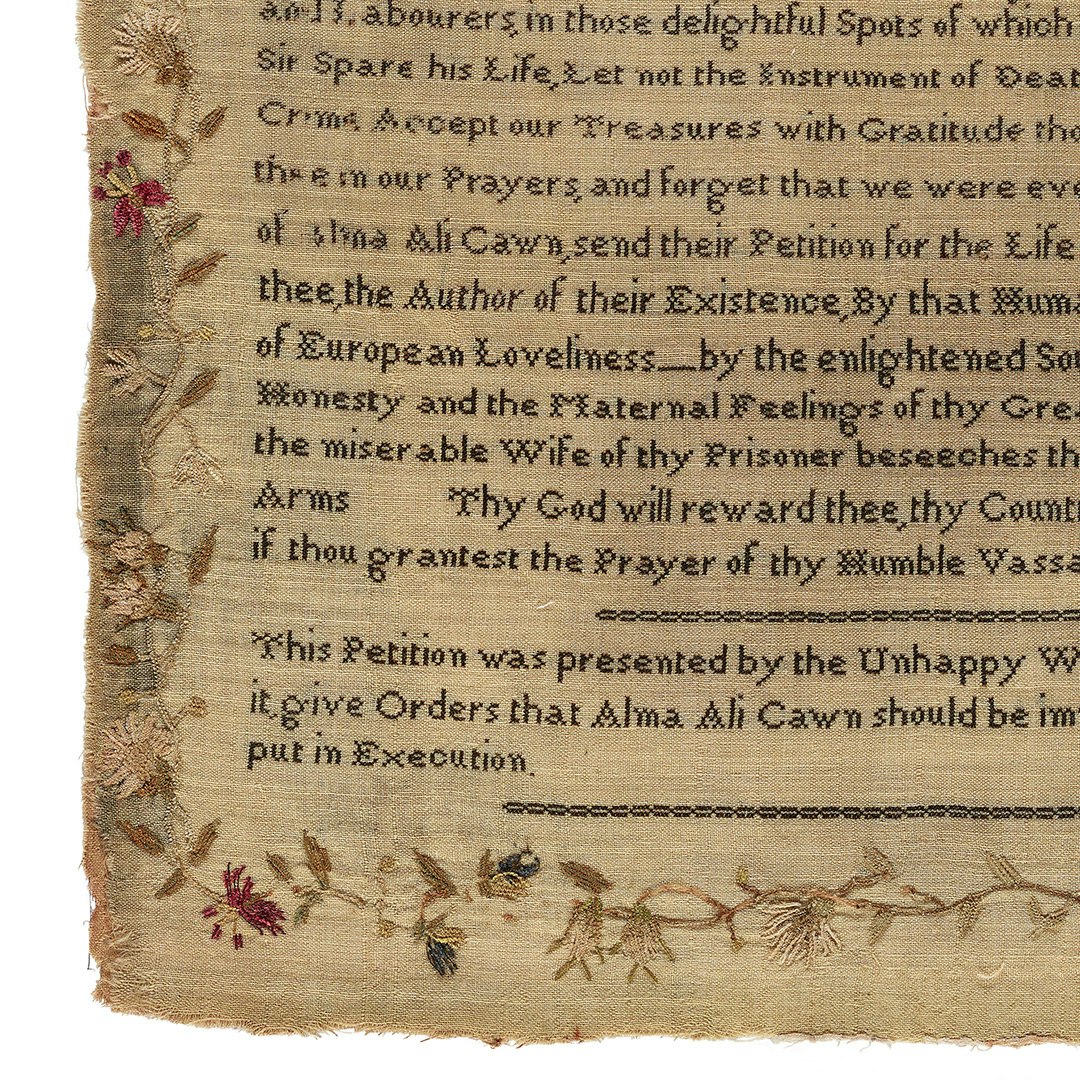

At first glance, the sizable, text-heavy, and largely monochrome embroidery is curious. It begins, “THE SUBSTANCE OF A PETITION Presented to W____n H___t___s Esq/By the Wife of/ALMA ALI CAWN/Who was put to death in India for Political Purposes” and concludes, “This Petition was presented by the Unhappy Woman to the Great Man, who when He had perused it give Orders that Alma Ali Cawn should be immediately strangled which Orders were instantly put in Execution./Hannah Powell 1813.” The document is rife with pain and desperation, including this anguished plea: “Give me back my Alma Ali Cawn, and take all our Wealth, strip us of our Jewels and precious Stones of our Gold and Silver but take not away the Life of my Husband, Innocence is seated on his Brow, and the Milk of Human Kindness flows round his Heart” and “My Children the Children of Alma Ali Cawn, send their Petition for the Life of him who gave them Life They petition from thee, the Author of their Existence, By that Humanity which we have oft been told glows in the Breast of European Loveliness.”

The Mystery Begins

But what is this petition, this passionate diatribe? Who is “W____n H___t___s,” and who are Alma Ali Cawn and Hannah Powell? Are they related by blood, friendship, circumstance, or something else entirely? I will try to answer these questions by exploring stitcher Hannah Powell’s source material to understand more about her political leanings, her access to literature, and the world in which she lived.

A Google search reveals that Alma (more often spelled Almas) Ali Cawn (occasionally spelled Khan) was a prince of the Oudh State, now in the Awadh region of northern India. He ruled over a fertile region adjacent to land that had been usurped by the British crown. Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of British India from 1779 to 1784, wanted Cawn’s land. Warren Hastings is the W____n H___t___s addressed in the embroidered petition.

Hastings falsely claimed that Cawn was inciting political unrest against the English, leading to Cawn’s arrest. Almasa (sometimes spelled Almassa) Ali Cawn, Cawn’s wife, wrote to Hastings to beg for her husband’s life. It is this desperate plea that was stitched onto the LACMA embroidery. In it, Almasa offered Hastings all of her family’s riches in exchange for Alma’s safe return. Hastings agreed to free Alma, but when Almasa arrived at the prison, she found her husband’s lifeless body. Hastings returned to England in 1785, where he was impeached by the House of Commons for his crimes in India (with Cawn’s murder just one of many transgressions).

His nearly 10-year trial ended with Hastings voted not guilty of oppressive treatment and corruption. In the final years of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, the tide of public opinion turned strongly in favor of Hastings, and he was granted an honorary doctorate from Oxford University and made a privy councillor. It is not known what happened to Almasa in the years following her husband’s murder.

Detail of Embroidered Document (Petition Against Execution), Hannah Powell, 1813

Detail of Embroidered Document (Petition Against Execution), Hannah Powell, 1813

Hannah Powell

Understanding the context of the embroidered petition reveals the identities of W____n H___t___s and Alma Ali Cawn, but who is Hannah Powell? A name as common as Hannah Powell makes it nearly impossible to conclusively identify which person by that name stitched the sampler, but understanding how, where, and when Almasa Ali Cawn’s petition was published tells us a bit more about the indeterminate Powell. It is likely that Almasa wrote her petition in her native tongue sometime before Hastings returned to England in 1785.

It was then translated (although it is unclear if the translator[s] dramatized its style to reflect anti-Hastings public opinion) and published in numerous forms and across a wide variety of printed media during Hastings’ trial. The earliest extant translation of the petition, featured in Mark Chartres’s 1791 book, The Elegiac Lyre: A Collection of Original Poetry (published in Dublin and printed by Bernard Dornin), is a rhyming “Poetical Translation of the Petition, Said to Have Been Presented by the Wife of Almas Ali Cawn.” The earliest surviving publication of the version Powell stitched, with only slight variations in spelling and grammar, is found in the 1795 book Variety: A Collection of Miscellanies, in Verse and Prose, published in Dublin by R. M. Butler the year Hastings was acquitted. Its presence in a collection of miscellany suggests this translation of Almasa’s poem had already been well circulated and widely published.

Almasa’s petition was published repeatedly in Britain and the United States from the 1790s through the 1840s, appearing in books, newspapers, broadsides, and even elocution guides. A letter, supposedly by Almasa, was translated and put into blank verse by an American named Joseph Brown Ladd in 1786. After it was first published in Charleston, South Carolina, in Ladd’s book The Poems of Arouet, it was printed repeatedly in American newspapers.

An uptick in the publication of both the petition and Ladd’s poem in 1813 was likely connected to anti-British sentiment during the War of 1812, which saw the United States and Great Britain pitted against each other over Britain’s violation of American maritime rights. Given that Hannah Powell tells us she stitched the embroidery in 1813, it is almost certain that she stitched it because of her family’s, her teacher’s, or her own dislike of the British.

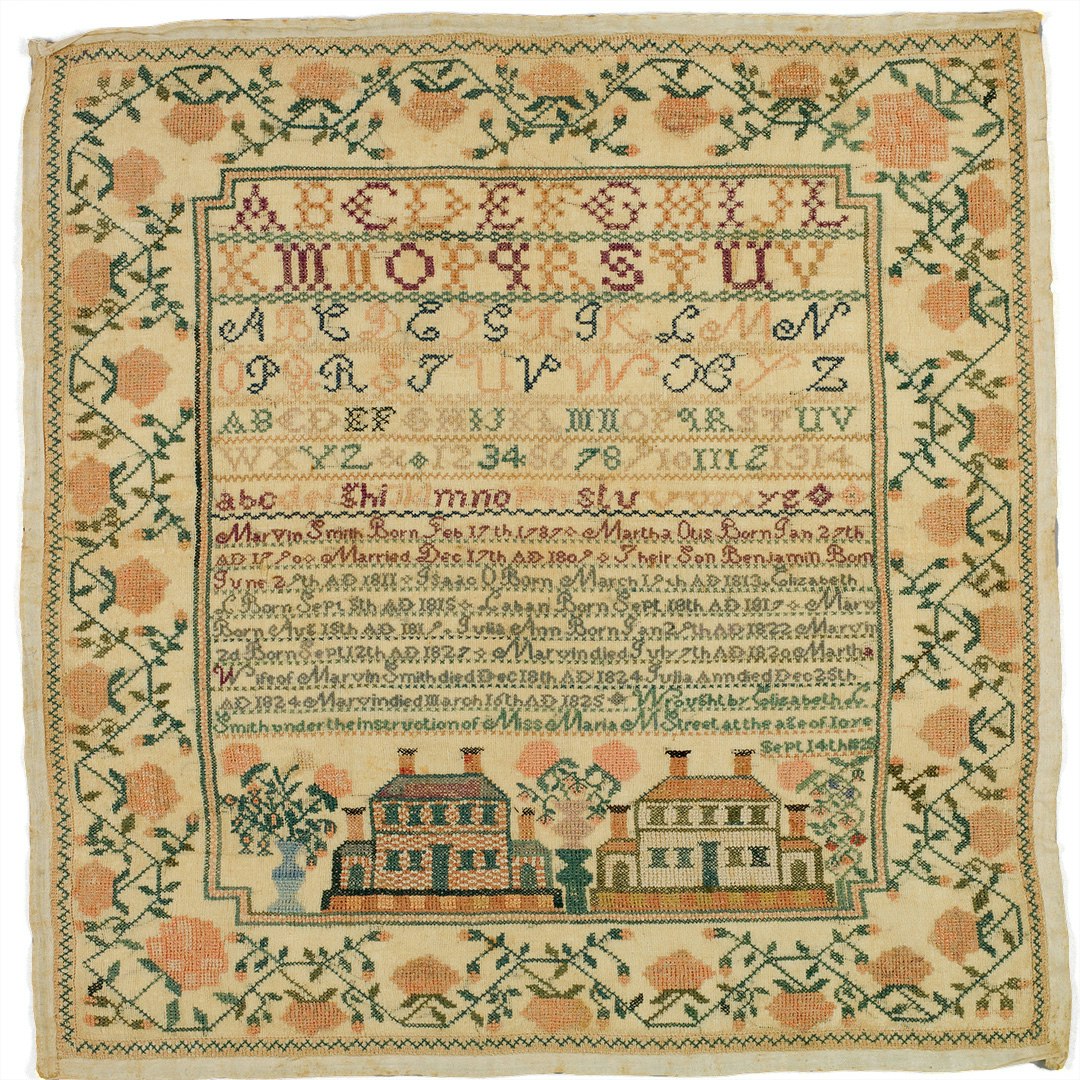

I mention Hannah Powell’s family and her teacher because she was surely no older than a teenager when she stitched Almasa’s petition. Although the choice of text is unusual, Powell’s work is a sampler, and one that is fairly typical of its time. Early nineteenth-century samplers often feature bands of text framed by a floral border, as does Hannah’s, though her sampler includes significantly more text than its contemporaries.

An Examination of the Sampler

At nearly 26 inches long and 20 inches wide, it is typical of the period’s large samplers, as is the prevalence of cross-stitch and the use of lustrous silk and chenille threads along its four borders. Less typical is the sampler’s ground fabric, which is a very finely woven, unbleached, soft wool. Most American samplers of that period were worked on linen. All of the text on Powell’s sampler is a somber black, accompanied by leafy, flowering stems of green, tan, white, magenta, and blue threads.

The sampler in a museum collection that is most similar to Hannah Powell’s is one stitched by Elizabeth Parker, an English nurserymaid who put her sad story about servitude, mistreatment, and thoughts of suicide into stitch around 1830. The sampler is now at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Like Powell, Parker covers nearly all of the fabric ground with tiny, neat letters in cross-stitches. Parker’s words reveal desperation, longing, and deep emotion. For both Powell and Parker, stitch was a way to ruminate on their own struggles or the distress of others through the use of a medium often more enduring than paper. These pieces narrate gendered repression or futility while also exhibiting the degree of creativity offered by stitching. Limitation and freedom are juxtaposed.

Embroidered sampler by Elizabeth L. Smith (1815–1841), 1825. Embroidered silk on cotton, 22¾ × 21¼ in. (57.8 × 54 cm). Purchase, Joel B. Leff Gift, 2000. Accession Number: 2000.482 Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Embroidered sampler by Elizabeth L. Smith (1815–1841), 1825. Embroidered silk on cotton, 22¾ × 21¼ in. (57.8 × 54 cm). Purchase, Joel B. Leff Gift, 2000. Accession Number: 2000.482 Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In addition to reflecting anti-British sentiment, the choice of verse by Powell or her teacher taught her about passion, death, injustice, and wifely fidelity. Powell’s sampler follows a long line of needlework that communicates political frustration, a theme that can be traced from the imprisonment embroidery of Mary, Queen of Scots, to suffragette banners, to contemporary stitched social statements.

And on a more practical level, the length of Almasa’s petition gave Powell ample opportunity to practice her eloquence—perhaps saying each word aloud as she stitched—and her stitching of letters prepared her for a life of marking household linens and undergarments with initials. By choosing to stitch Almasa’s petition, Powell combined the political and functional. Her sampler gives modern viewers a glimpse into the political experience of girlhood in the young American republic at war.

At first glance, Hannah Powell’s embroidered petition is shrouded in mystery. And even a thousand glances later, much of the puzzle remains unsolved. Although research reveals the source of the lengthy inscription, its major players, and its publication history as well as the way Hannah Powell most likely came across the inscription’s source, we still do not know exactly who Hannah Powell was or why she stitched Almasa’s desperate plea. But we do know that Powell’s piece embodies the power of embroidery to convey emotion and the many layers of womanhood inherent in so much historical stitching—a girl, under the instruction of a female teacher, stitched the words of a grieving and aggrieved woman on the other side of the world. And through this stitching we can learn of a teenager about whom we know nothing beyond her name. Her embroidery tells us about her and her family’s political leanings, the type of print media she read, and the tarnished reputation of the British empire in the first decades of American independence.

Interesting in searching for more myths and mysteries hidden in stitchwork? This article and others can be found in the Summer 2023 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Summer 2023. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Isabella Rosner is a final-year PhD student at King’s College London, where she researches Quaker women’s art before 1800. Her project focuses on seventeenth-century London needlework and eighteenth-century Philadelphia wax and shellwork. Isabella also specializes in the study of schoolgirl samplers and early modern stitching and hosts the Sew What? podcast about historic needlework and those who stitched it.