The First World War (1914–1918) witnessed an unprecedented knitting frenzy. On the home front, everyday concerns faded into the background as civilians sought ways to express patriotism and support the troops. Practical, portable knitting proved especially patriotic.

Among working class and elite, young and old, in solitude and in society, knitters on both sides of the Atlantic produced extraordinary numbers of knitted “comforts” for the troops. Following America’s entry into the war in 1917, events such as New York’s Big Knitting Bee in Central Park on July 30, 1918, shone a spotlight on knitting. The August 2, 1918, issue of The Stars and Stripes reported:

Democracy at its knitting will no doubt be photographed and feted to a fare-ye-well, but the prospects are that the Yanks over there . . . will not be allowed to get chillblains [sic] anywhere else, not even on their trigger-fingers. “Quantity production” is the aim of the knit-fest.

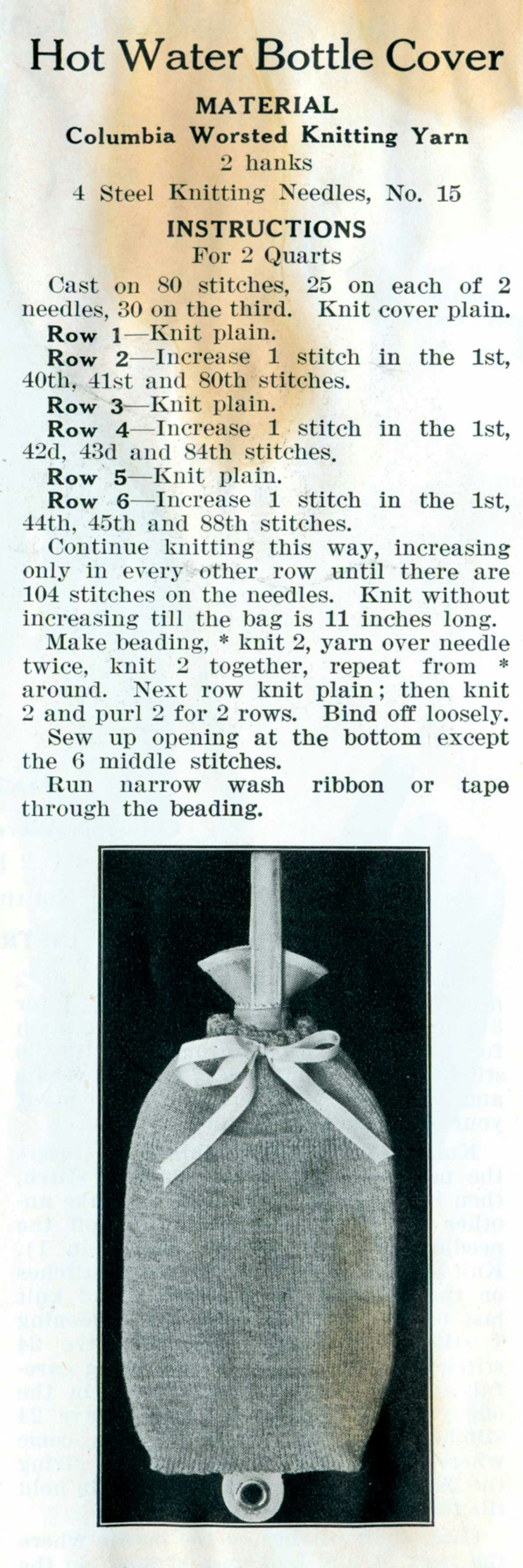

Photograph and pattern instructions for a Hot Water Bottle Cover from the Columbia Yarns pattern book, Comforts for the Men. Collection of the author.

Across the Atlantic, British knitting had reached manic proportions by 1915, the year after Britain entered the war. Everyone, everywhere, seemed to be knitting comforts for soldiers and sailors. The women in service at Downton Abbey would have expected to knit for war support. As lady’s maid, O’Brien’s duties already included mending and needlework for Lady Grantham. The housemaid Anna and the kitchen maid Daisy likely knitted for their own practical needs. Knitting would have proven an especially useful and patriotic skill when Downton Abbey established a hospital for wounded officers. Although the middle daughter, Lady Edith, found fulfillment in strenuous farm work, few middle- or upper-class wives and daughters volunteered for war work in factories, the military, or farming. Knitting, however, would have been appropriate war work for the aristocratic ladies of Downton Abbey.

Knitting also gave comfort to many who picked up yarn and needles. In A History of Hand Knitting, Richard Rutt quotes a wartime knitter, Dorothy Peel: “It was soothing to our nerves to knit, and comforting to think that the results of our labours might save some man something of hardship and misery, for always the knowledge of what our men suffered haunted us.”

What comforts did soldiers and sailors need? Where did knitters find patterns? More to the point, what might those both above and below stairs at Downton have been knitting during World War I?

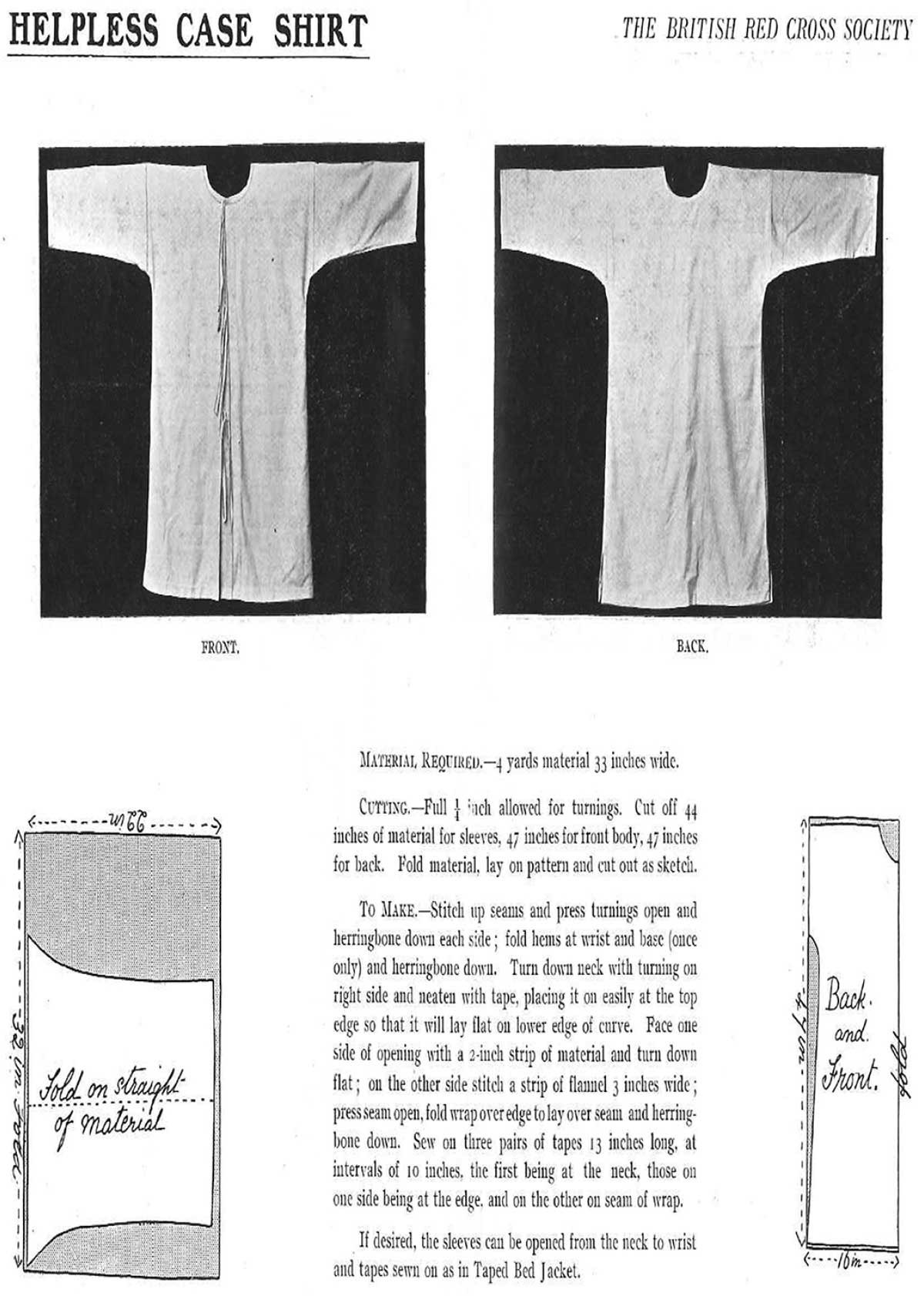

The British Red Cross, yarn companies, and women’s magazines all published knitting patterns. The British Red Cross Society Needlework and Knitting Instructions guided British needleworkers in sewing and knitting comforts for active and wounded servicemen. The booklet assures that “Matrons of some of our leading hospitals” had approved the actual garments shown in the photographs and that “all the patterns illustrated and described in this book have been designed to combine accuracy of fit with the least possible amount of work.” Clearly, time was of the essence in sewing and knitting for victims of the war. Only the names given to patterns for sewn garments evoke the reality of hospitalization and convalescence: Taped Bed Jacket, Enteric Shirt (Open all down Back), Patient’s Operation Gown, Pyjamas, Night Shirt, Day Shirt, and Helpless Case Shirt. The Helpless Case Shirt, a short tunic closed with ties on front and sleeves, sends a chill up the spine.

A photograph and pattern for sewing the Helpless Case Shirt from the British Red Cross Society pattern booklet. Collection of the author.

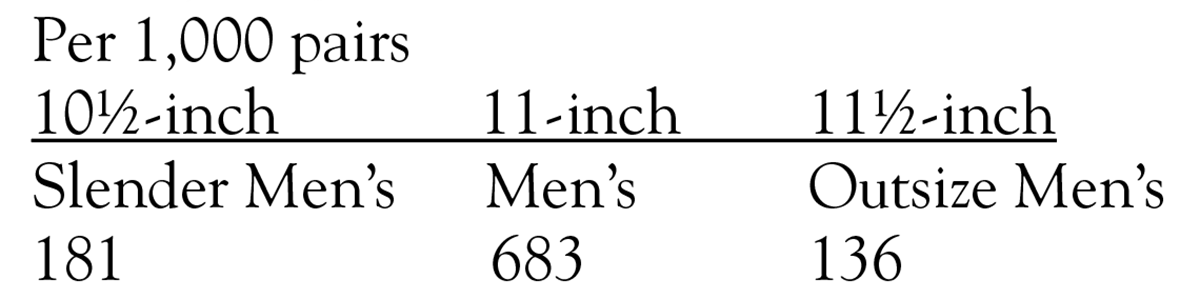

Names of knitting patterns in The British Red Cross Society Needlework and Knitting Instructions also indicate hospital use: Heel-less Operation Stocking, Heel-less Bed Sock, Woollen Slippers, Cardigan Jacket, and Day Sock. The hospital stocking and bed sock call for white double knitting wool with 68 and 60 cast-on stitches, respectively. Evidently, the British Red Cross Society considered the need for socks especially pressing; the booklet specifies the ratio of sizes required (by length of foot) according to Army issue:

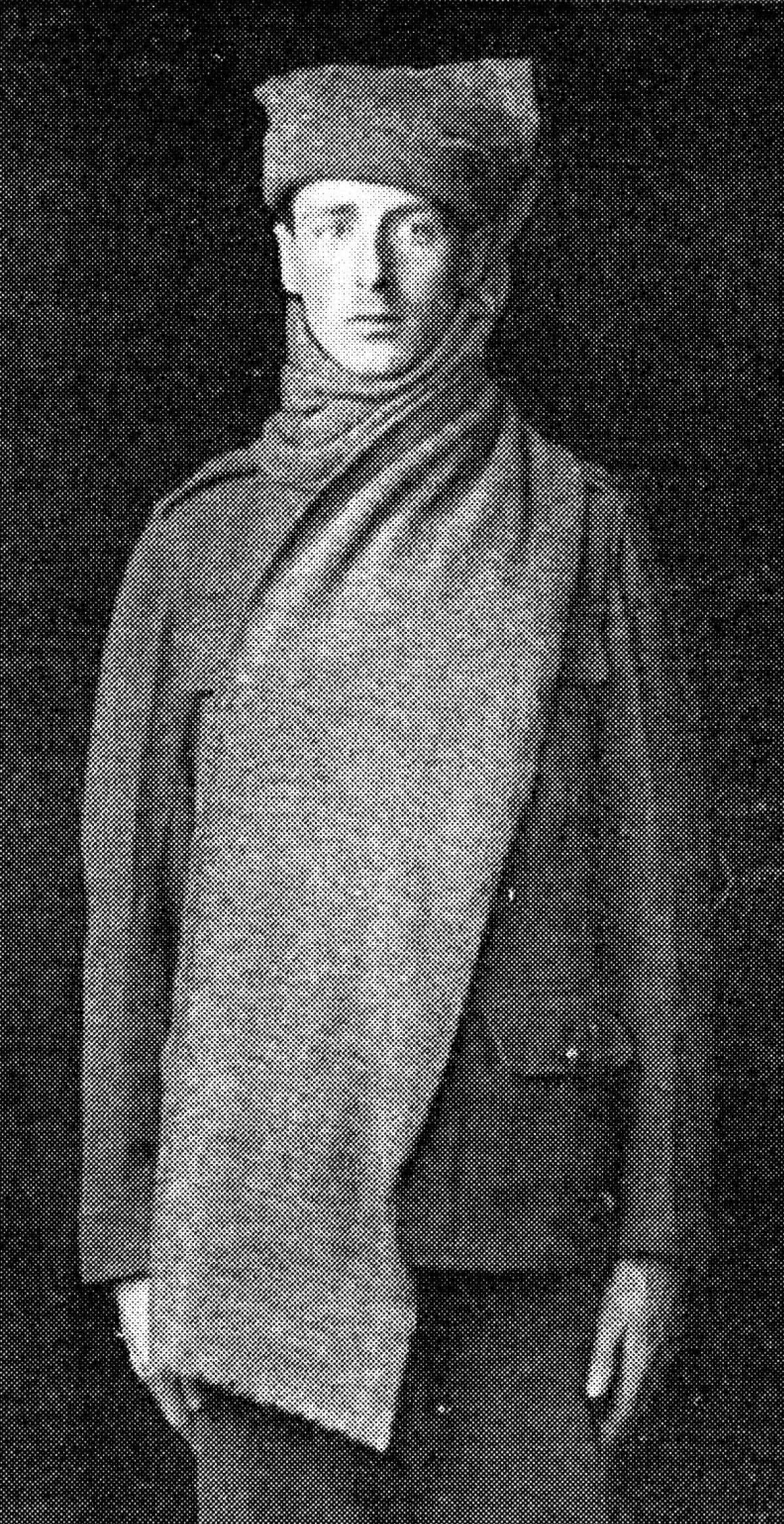

Other knitted comforts seem destined for servicemen on land and at sea. Men on the frigid North Sea confronted dangers from mines and torpedoes while men on land at the Western Front dug deep into trenches. The untold suffering and carnage receives only a hint in the pattern names of the British Red Cross booklet: Cardigan Jacket, Knitted Cap, Woolen Belt or Cummerbund, Woollen Gloves, and Fingerless Mittens. The intriguing Cap Scarf consists of a long tube knitted either in the round on four needles or in rows of double knitting using two needles. The Cap Scarf could be worn as an especially thick muffler, or one end could be turned inside the other to make a cap leaving a generous length that wrapped around the neck, fell to cover the chest, and reached well below the waist. Interestingly, instructions encourage the knitter to adapt the pattern to any weight of yarn by making a swatch to determine gauge though these terms are not used.

The photograph of the intriguing knitted Cap Scarf from the British Red Cross Society pattern booklet. Collection of the author.

The patriotic knitters of Britain also found patterns in yarn company booklets and women’s magazines. The prominent yarn company J. and J. Baldwin of Halifax published Knitted Comforts for Men on Land and Sea with most patterns attributed to Marjory Tillotson (1886–1965). (The attribution is unusual for the time. After the war, Tillotson would become the leading designer of handknits in England and the author of The Complete Knitting Book, first published in 1933 by Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons of London and a standard for decades on the subject of knitting.)

Patterns for comforts also appear in England’s Woman’s Own Knitting & Crochet Supplements, spinoffs from Woman’s Own Magazine. Woman’s Own even sponsored a Patriotic Knitting Competition. The Supplements, most undated, include the following patterns:

- Combination Cap and Muffler [similar to the British Red Cross Cap Scarf]

- Trench Gloves [with long cuff that fits over coat sleeve]

- Shetland Helmet and Mittens [balaclava with holes for ears, shooting mittens with separate thumb and first finger open at top]

- Hose Tops for Highland Regiments [knee sock with ribbed cuff at ankle, no foot, and deep turnover cuff that can be unfolded to cover knee]

- Sailor’s Muffler with Anchor Border [knit and purl stitches create motif]

- The New Trench Cap or Helmet [earflaps button under chin or on top of head]

- Shetland Helmet [balaclava loose around the face and described as “the ideal sleeping helmet for warmer weather”]

- Chest Protector [a rectangle with head opening and straps at waist]

- Comfortable Body Belt [a tube 9 inches (22.9 cm) deep]

- Knitted Cover for Hot-Water Bottle

One Knitting & Crochet Supplement in particular tugs at knitting heartstrings with “Warm Comforts for which Our Soldiers and Sailors will Thank You.” These include Steering Gloves [mittens for men on trawlers], Gauntlet Gloves [that fit over coat sleeves], Stockings for Sea Boots [for sailors or fishermen who did minesweeping], and Campaign Bonnet [with buttons to the chin and turn-back cuff around the face]. Another supplement specializes in knitting patterns for wounded limbs: Footless Stocking, Covering for a Bandaged Foot, and Covering for a Bandaged Arm [shaped to fit the elbow].

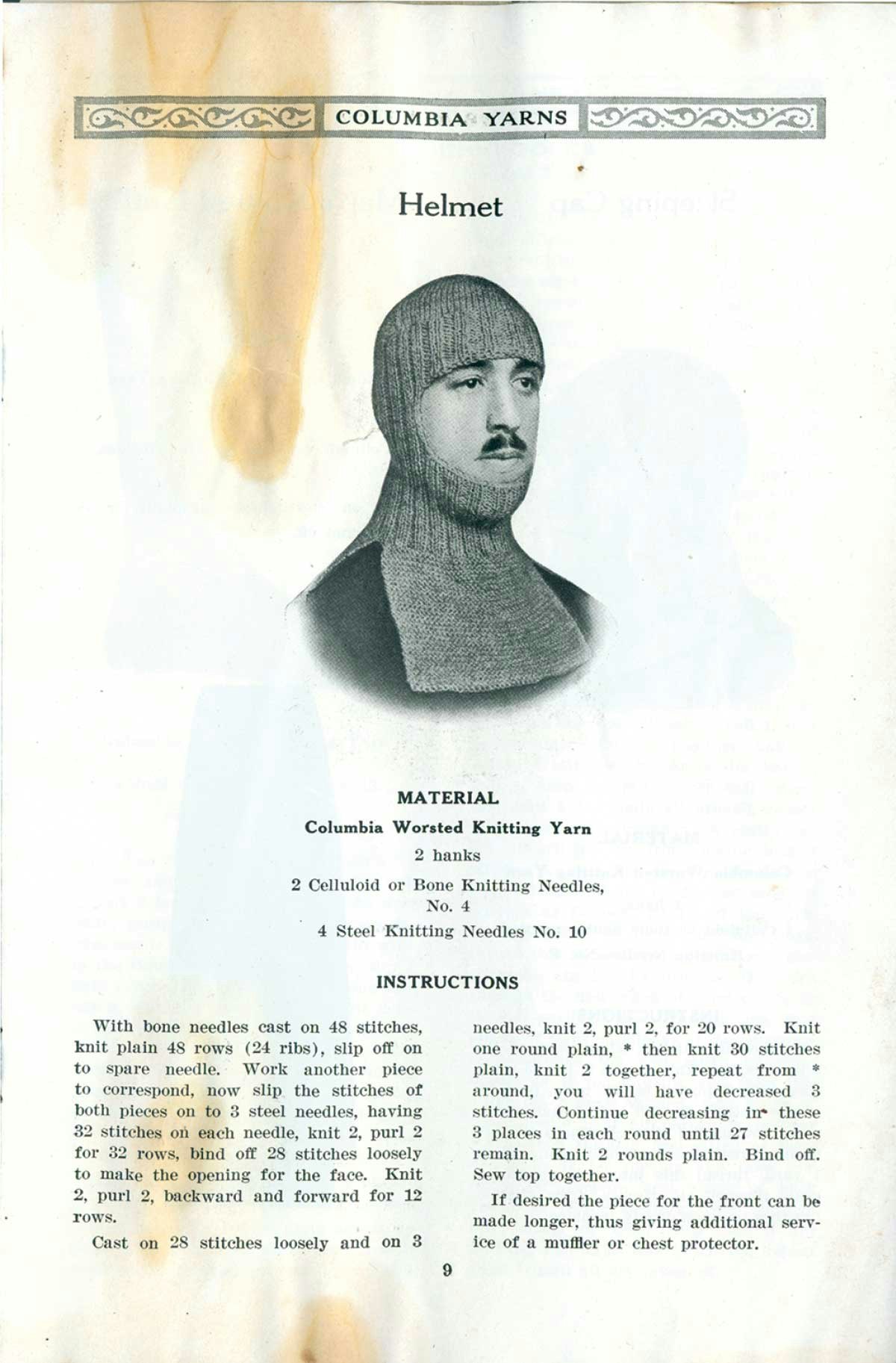

Photograph and pattern instructions for a Helmet pattern from the Columbia Yarns pattern book, Comforts for the Men. Collection of the author.

The Lady’s World Fancy Work Book, published in London, was another pattern resource. The first issue after war was declared in August 1914 mentions the war only in advertisements from spinners offering to sell yarn to make comforts for the troops. The January 1915 issue, however, contains patterns for knitted comforts and the following: “So many comforts have been knitted for soldiers, but we fear comforts for sailors are being overlooked, and we would remind the home worker of the need of scarves, sweaters, stockings, mittens, etc. that is experienced by men in the North Sea at this time of year.” The issue corrects this oversight with patterns for a Knitted Scarf and Cap for Soldier or Sailor [similar to the Red Cross Society’s Cap Scarf], Knitted Body Belt, Sleeping Helmet [balaclava], Sea-boot Stocking, and Seaman’s Jersey. More knitting patterns follow in subsequent issues: April 1915—Man’s Knitted Mittens [fingerless], An Easily Made Cardigan Jacket for Soldier or Sailor [strips of plain knitting joined together]; October 1915—Knitted Shoe for Wounded Soldier, Khaki Puttee Footless Stockings [presumably worn beneath puttees, strips of cloth wrapped around the calves], Gentleman’s Pants and Vest [underwear but not specified for servicemen]; January 1916—Warm Bed-Socks for Cold Feet, Soldier’s Glove-Mitten with Divided Palm [a flip-top mitten], The New Trench Hose [waterproofed in linseed oil and worn over regular socks].

The British Red Cross Society undated pattern booklet. Collection of the author.

Patterns for comforts in The Lady’s World Fancy Work Book dwindle to none after the middle of 1916 with the exception of one final pattern in 1918 for the Warm Woollen Scarf Suitable for the Sea, the Baltic Front or the Air for the Troops. The emphasis shifts back to fancywork crochet patterns, especially filet crochet, for the home. Perhaps knitters had all the comfort patterns they needed, and there was no reason to publish more. On the other hand, the war was making additional demands on the time and talents of wartime knitters. Serious recruitment of working-class women from low-paid service jobs into factory work and transportation was well under way in 1915, and Britain also allowed women to enter the army, navy, and air corps in supporting roles that released men to serve at the front. British feminists were calling for women’s right to serve and prove themselves worthy of such civil rights as the vote, although, as Lady Edith in Downton Abbey discovered, this “reward” for women was limited to those more than thirty years old.

After the war, the role of British women returned to making life as normal as possible. Men came home with physical and mental scars, and many women who lost husbands, fathers, and brothers were left to raise children on their own. Industries dismissed female factory workers, and married women were barred from many white-collar jobs. The schoolchildren who had learned to knit and all ages of women (the primary though not exclusive wartime knitters), however, made the transition from knitting comforts for the troops to knitting garments for themselves and their families, especially stylish dresses and sweaters so well suited to a the more active postwar lifestyle. Postwar knitters carried on, perhaps relying on knitting for their own comfort.

Resources

- Peel, Dorothy Constance Bayliff. How We Lived Then, 1914–1918. 1929. Reprint, Ann Arbor, Michigan: Books on Demand, n.d.

- Rutt, Richard. A History of Hand Knitting. 1987. 2nd ed. Loveland, Colorado: Interweave, 2003.

- Strachan, Hew, ed. World War I: A History. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1998. Out of print.

- The Knitting & Crochet Guild in the U.K. holds a collection with bundles of patterns removed from Woman’s Own Knitting & Crochet Supplements and more than fifty issues of Fancy Work Book; www.kcguild.org.uk.

Susan Strawn knits from the past, especially from cultural and historical traditions found in vintage patterns and handknits. She is professor emerita of apparel design and merchandising at Dominican University (Chicago) and author of Knitting America: A Glorious History from Warm Socks to High Art (Voyageur, 2007).

This article was published in The Unofficial Downton Abbey Knits 2013.