It holds a place of pride on a shelf in my office: an unassuming framed piece, about 9 by 11 inches, holding the beginnings of a tiny four-selvedge rug woven with handspun wool, dyed in seven different colors from plants native to the Navajo Nation. A family member found it in a little shop somewhere in Oklahoma, but its home of origin was New Mexico, south of Gallup near the tiny community of Pine Springs.

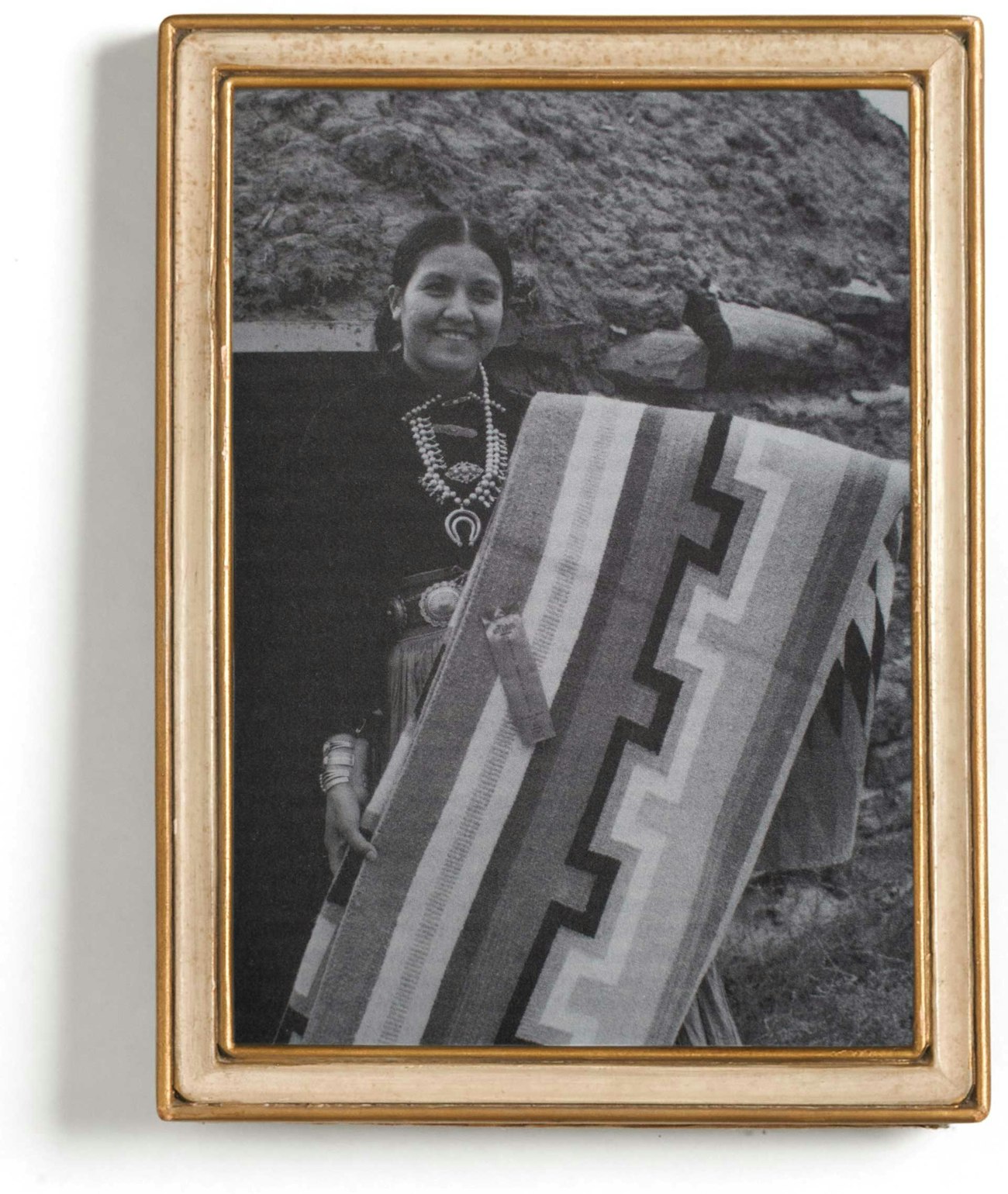

Mabel Burnside Myers

That’s where the family of Mabel Burnside Myers has continued to produce these cultural treasures: spinning the yarn, gathering the plants, dyeing, labeling, weaving. It’s not a trivial undertaking. They’re continuing a project begun by their mother, their grandmother, some 70 years ago.

Her life had been remarkable. Born in 1922 and graduated from high school in 1938, Mabel Burnside was head of the weaving department at the tribal vocational school in Shiprock before she was thirty. She had participated in the beginnings of a natural-dye book at Fort Wingate Vocational High School much earlier than that; she’s remembered as carrying sample cards wrapped in dyed yarn to serve as reference as she taught the skills. This was just a couple of years after high school.

Pine Springs and her family—which included five children—called her home, though. We see her weaving in her hogan in a National Educational Television documentary film (The Navajo [Part I]: The Search for America) made in 1958. In her soft-spoken way, she affirmed that being home with family and weaving were more important than the generous salary she had received working in Shiprock. She shows a rug, a masterpiece, that she had woven using 85 natural-dyed colors.

A portrait of Mabel Burnside Myers as a young woman with one of her prize-winning rugs. Photo by Don Dedera, published here with permission of the Dedera family

This mastery of such a wide range of dye colors somehow led to the idea of presenting them in a unique format, attractive to collectors and museums and tourists. Creating the framed charts became a little cottage industry for her family. Her children and grandchildren have memories of driving along the remote roads of the Navajo Nation, collecting leaves and twigs and berries along the way and then watching the colors emerge in the boiling vats in their hogan.

Continuing Her Legacy

Mabel’s daughter, Isabel Deschinny, began to learn the dyes from her mother when she was only ten, and she has led the project since her mother’s passing in 1978. In fact, her framed chart featuring 87 colors took overall Best of Show at the Navajo Nation Fine Arts Fair in 2019. It’s a majestic 3 feet by 6 feet, with an exquisite miniature rug at its heart.

My little piece, some colors faded with age, must be one of many hundreds, or even thousands, produced by Mabel Burnside Myers and the Deschinny family. You can find charts of all sizes and complexity in galleries and on eBay, selling for many hundreds of dollars. They are all true to the original: carefully warped little four-selvedge rugs, neatly typed plant labels in English and Navajo, alive with the colors of the land.

For this and other stories that invite you to question everything you know about natural dyes, including a deep dive into the lives and times of a family of professional dyers in eighteenth-century England, an armchair traveler's visit to block-print and batik studios in the Indian Kutch district, and more, pick up a copy of Nature's Colorways by Long Thread Media.

Originally published October 27, 2021; updated September 22, 2025.