In late December, the needlework community said goodbye to one of its most influential and beloved figures. Barbara G. Walker was a cherished voice who transformed how generations of knitters approach and understand their craft. For us at PieceWork, Barbara represents the heart of knitting as we know it: patient, curious, historically grounded, and deeply human. Her legacy lives in every thoughtful stitch cast on. In remembrance of her extraordinary life, we share “My Knitting Life,” an article she wrote for PieceWork in Fall 2024. —Karen Elting Brock

My Knitting Life: A Facet of a Life in Full

My life has been a series of obsessions. In my teens, it was horses. I spent all my available time on horseback, even taking a prize in the Devon Horse Show in Devon, Pennsylvania. In my twenties, my passion was dance—modern dance in the style of Martha Graham. In my thirties, after our son had started school and I had time on my hands, knitting became my obsession. This obsession came as a surprise because, while I was an honor student and a Phi Beta Kappa in college, I was a complete idiot when a sorority sister tried to teach me to knit. I just couldn’t get it. I made a hopelessly messy, ragged swatch, threw it away, and said that knitting was not for me.

Then when I was in my mid-thirties, a wife and mother, making my clothes on my sewing machine, I thought some homemade sweaters would be nice after all. I resolved to try it again. I taught myself from a little “Learn to Knit” pamphlet published by Bernat and started to follow a commercial design for a plain stockinette sweater. Before I reached the end of this project, I was intensely bored by its super-repetitive operation.

Resurrecting and Creating Stitch Patterns

Then came a revelation: some knitting magazines showed me that sweaters could be made with different pattern stitches! This was the beginning of my new obsession. I immediately began making a collection of these interesting variations. While the United States had no readily available books on traditional patterns, I found collections by James Norbury and Mary Thomas published in England and added them to my list. I even went to the stacks in the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, to collect historical examples. After that original stockinette sweater, I never again followed anyone else’s directions for a garment. All my garments were made up as I went along, adjusting for gauge and using all sorts of novel patterns.

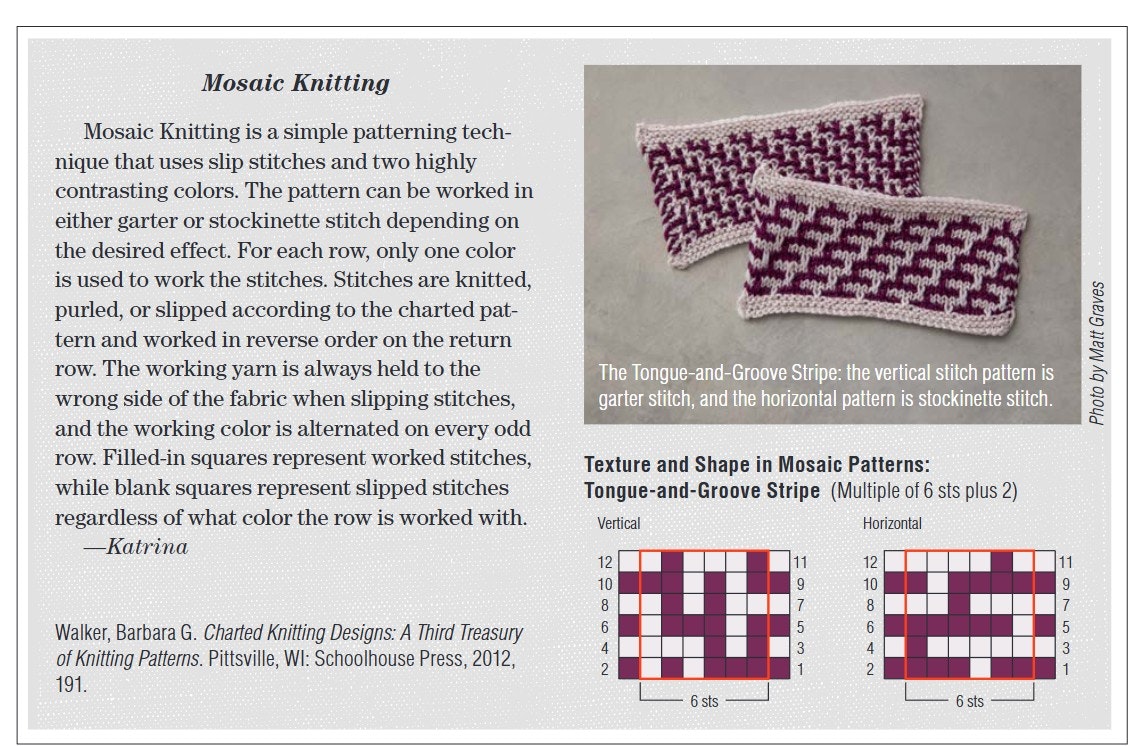

After a few years of earnest collecting, I had hundreds of patterns, sorted into the categories of Simple Knit-Purl Combinations, Ribbings, Color-Change Patterns, Slip-Stitch Patterns, Twist-Stitch Patterns, Fancy Texture Patterns, Yarn-Over Patterns, Eyelet Patterns, Lace, Cables, and Cable-Stitch Patterns. This collection was published in 1968 as A Treasury of Knitting Patterns. At the end of the book, I invited knitters to contribute any other patterns that might have been handed down in their families. A number of readers responded, and in addition to these, I was beginning to invent my own original patterns. The collection grew and grew and became the much larger A Second Treasury of Knitting Patterns published in 1970. This book had some new categories, such as Fancy Color Patterns, Fancy Texture Patterns, Lace Panels and Insertions, Borders, Edgings, and the now-famous two-color designs of my own inspiration, which I named Mosaic Knitting, a term that I invented for my new colorwork technique. This is an easy technique that uses only one color at a time, switching every second row or round, without the bother of stranding. When I first visualized this technique, I wondered, “Why didn’t people think of this before!”

Two years later, tired of writing so many patterns as line-by-line text directions, I invented a way to show the directions with graph paper on a chart, which could actually resemble the pattern and make it clearer. I’ve always seen patterns in things, so it was natural for me to see knitted patterns as symbolic charts rather than as lines of words. Many knitters are now using this system.

I continued to invent my own patterns and published them in a 1972 book called Charted Knitting Designs, which was also published later as A Third Treasury of Knitting Patterns. This was followed in 1973 by A Fourth Treasury of Knitting Patterns, which was previously entitled Sampler Knitting; then in 1976 came Mosaic Knitting. All the designs in these later three books were my own creations, amounting to more than one thousand brand-new, original patterns. All the swatches for all of my books were made by my own hands. It seemed that the ideas just couldn’t stop coming.

Of course, it wasn’t just the swatches for the books that I was knitting. My obsession was manifested in the sheer volume of things I knitted: some 300 garments, 15 afghans, several bedspreads, and, not least, 600 highly detailed garments for 400 fashion and action-figure dolls I had collected. I made these tiny costumes to scale, using very fine yarns and triple-zero needles, about the thickness of hatpins.

Barbara G. Walker designed and knitted all of the tiny-gauge garments on these dolls. Photo courtesy of Meg Swansen

I also designed, handknitted, and wrote the directions for many garments that were sold to yarn companies for their publications. I did this for years, until I happened to go to a knitting convention and saw the very same garments that I had knitted, professionally modeled and sold for four or five times what I had been paid. That was when I stopped working for yarn companies.

Following Different Threads

At about the same time that I was deeply engaged in knitting, collecting, and inventing knitting patterns, I was avidly exploring historical roots of religion from a feminist point of view. This resulted in the publication of my first nonknitting book, The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, which came out in 1983 and won a Book of the Year Award from the London Times. This was followed by some artwork and design books: The Secrets of the Tarot (1984), The Barbara Walker Tarot Deck, and The I Ching of the Goddess (1984–1986), all illustrated by my paintings.

Then came more of my investigations into mythology and comparative religion: The Crone (1986), The Skeptical Feminist (1987), The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects (1988), The Book of Sacred Stones (1989), and Women’s Rituals (1990). Then, I wrote two works of fiction: Amazon: A Novel (1992) and Feminist Fairy Tales (1995). Next came Man Made God (2010) and finally, Belief & Unbelief (2014). I went through more than five hundred source books and histories, gathering information for these efforts.

A collection of knitting books by Barbara G. Walker. Photo courtesy of Meg Swansen

A collection of knitting books by Barbara G. Walker. Photo courtesy of Meg Swansen

Regarding knitwear design, I published two more books: Knitting from the Top (1972) and the Learn-to-Knit Afghan Book (1974). The first of these was a lesson on how to make seamless knitted garments in every possible style from the top down, which led to a much better fit than sewing together separate pieces as if they were fabric. It showed the true wonder of knitting, which is to make a whole garment out of what seems like a single, continuous thread, without sewing any seams at all. The second of these was a short course in learning to knit by making an afghan with different squares demonstrating different pattern types—knit-purl, slip-stitch, twist-stitch, mosaic, lace, cables, and special techniques—so the beginner could have a taste of each in short projects that could be finished promptly, before boredom set in; and afterward, they could be put all together as a useful afghan.

In addition, my basic directions taught European-style (Continental) knitting rather than the American style. I had learned the latter but switched to the former when I discovered that it was easier and faster. There was some current nonsense claiming that only left-handed people could use the European style since the yarn is held by the left hand rather than the right. In reality, it makes no difference whether you are left- or right-handed; knitting is a two-handed operation and can be learned just as easily either way.

Barbara G. Walker's Diamond Basketweave pattern from PieceWork, January/February 2010. Photo by Joe Coca.

Barbara G. Walker's Diamond Basketweave pattern from PieceWork, January/February 2010. Photo by Joe Coca.

One would think, with all these books and other items being produced, that I spent all my time at the desk or in the knitting chair. But I did have a real life apart from that: I taught classes in modern dance, I traveled all over the country to give talks and sign books, and I did the ordinary household chores. My husband and I regularly attended folk-dancing and square-dancing clubs.

For the latter, of course, we wore my homemade gowns and his matching homemade Western-style shirts. As a family, we did a lot of year-round hiking and biking and summer vacations at the shore. We lived in Switzerland for one year, climbing the Alps. My husband climbed the Matterhorn, a literal high point of his life.

Now that I’m in my tenth decade and less mobile, I obsess on puzzles—just the printed kinds of word puzzle books you find at the supermarket. Somehow this satisfies my need for finding order and patterns.

On the whole, it has been a wonderful journey. I became friends with two other noted knitting gurus, Mary Walker Phillips (no relation) and Elizabeth Zimmermann; together we became known as the Big Three, or Triumvirate. Another valued friend is Elizabeth’s daughter Meg Swansen, who has overseen the republication of my knitting books by Schoolhouse Press. Inspiration has come to me from many sources, and inspiration has gone out from me to a multitude. I feel satisfied with my life and glad to have contributed to the creativity of so many other people. I have been one of the fortunate ones, to have found fertile niches that challenged my mind, heart, and hands, and lived in them with joy.

Barbara G. Walker

To learn more about Barbara's remarkable life and accomplishments, visit her website BGW Works.