In the mid-1800s, a curious trend found its way from Europe to the United States, that of human hairwork. The Civil War was over. Consumerism was on the rise, and with it, a re-examination of the role of women in middle-class society. A fascination with hairwork emerged, both as a way to immortalize the deceased and as a way to sentimentalize the living. It also served as an expression of a woman’s valuable role in the home, highlighting her idealized attachment to children, friends, and a husband as a maker of decorative objects.

Hair Wreaths and Albums

Saving hair for future use in jewelry or other commemorative craft was routine for the middle and upper classes. Highly decorative hair jewelry, or “jewelry of sentiment,” was created as keepsake symbols of love and friendship.

Larger pieces, such as wreaths or family portraits embellished with floral or botanical motifs of hair art, often contained hair from multiple family members. Usually intended for the parlor wall, hair wreaths were visually dense, highly decorative objects that stood out because of their substantial size and appearance.

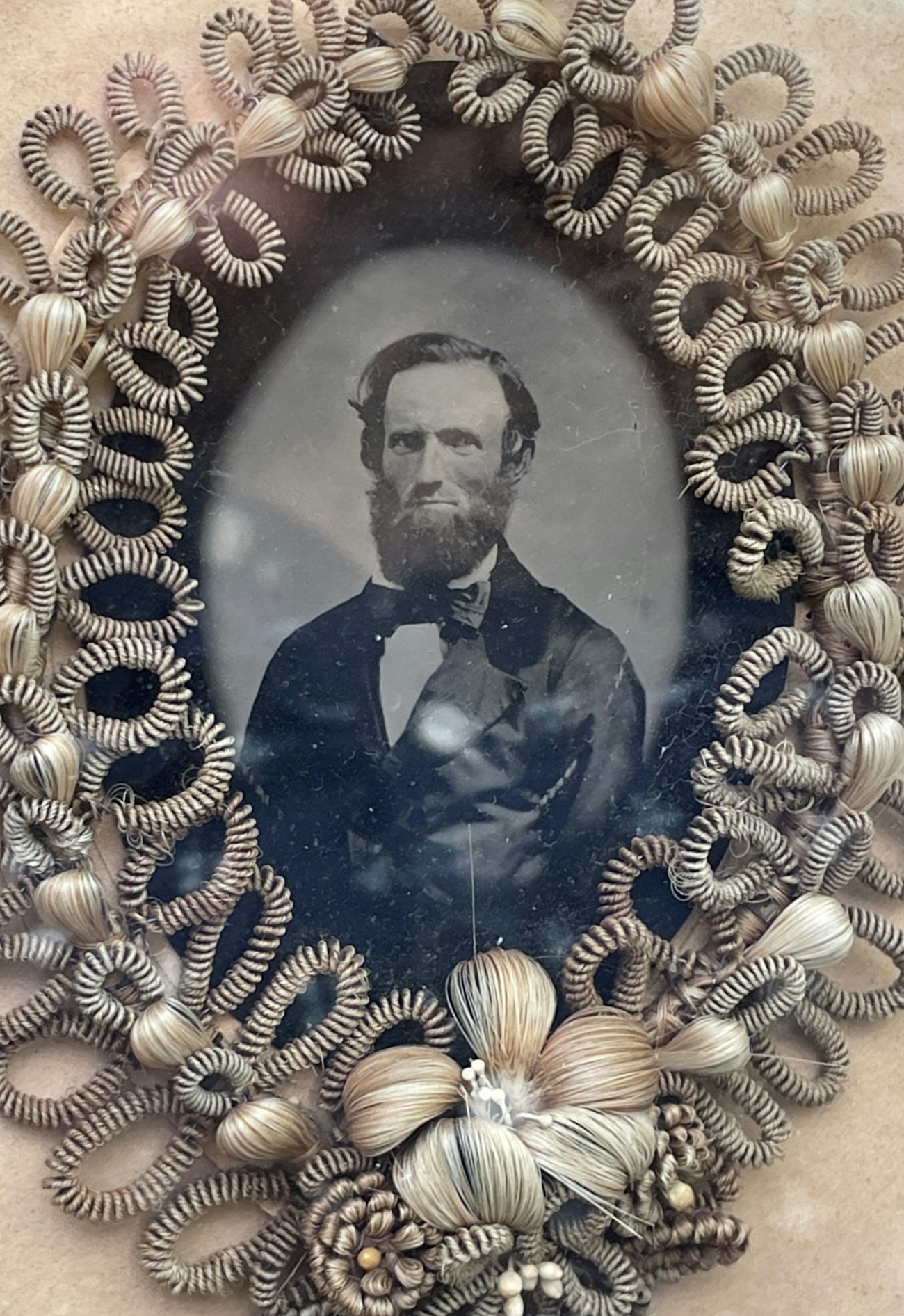

Mourning portrait of Raphael Ward Benton. Courtesy of The Guilford Keeping Society, Connecticut

Mourning portrait of Raphael Ward Benton. Courtesy of The Guilford Keeping Society, Connecticut

One example is the mourning portrait of Raphael Ward Benton (1821–1862), one of Guilford, Connecticut’s Civil War heroes who gave his life for the cause at Antietam, Maryland, on September 26, 1862. In his honor, a mourning portrait was created, featuring Mr. Benton’s photograph surrounded by an elaborate wreath of human hair worked into leaf, bud, flower, and pinecone shapes.

In addition to portraits, hair albums were a popular way to combine locks of hair with verse and inscriptions, serving as remembrances for both the living and the dead. An elaborate hair album is described In The Grandmothers, Glenway Wescott’s poignant story of nineteenth century Wisconsin:

In all, there were fifty-six names, badly faded, in a script full of old-fashioned flourishes, and fifty six garlands, having a variety of designs: braided hoops, medallions like bits of Spanish lace, and spider webs, combinations of loops and zigzags and coils and shadowy scallops, executed in every quality and shade of hair—gray of tin and gray of iron, sandy and chestnut and dead black, one maroon and one almost orange; fine, coarse, wiry, or subtle; long threads spread out in spirals, and threads not long enough to encircle a space as big as the end of one’s thumb, and stiff locks in which the form of a curl still pulled at the knots which held them.

Hairwork at Home

Before the nineteenth century, hairwork was created mostly by professionals, including jewelers and wig makers, but by 1850, making hairwork art at home became a popular craft. Between 1850 and 1859, Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book promoted hairwork as a lady’s drawing-room pastime, featuring articles and patterns detailing proper hair preparation and braiding techniques.

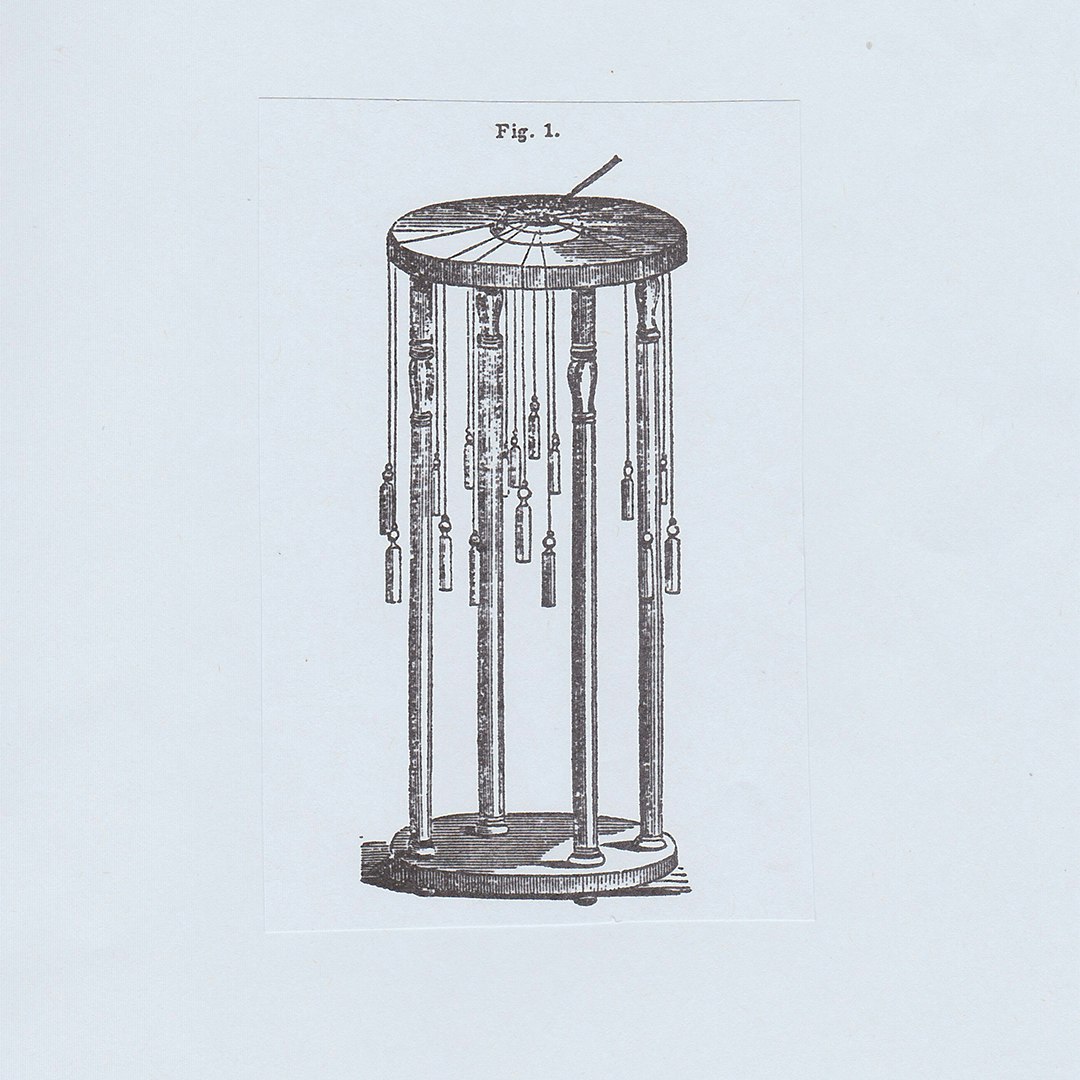

Illustration of a common type of hair-braiding table, including bobbins and weights, Godey’s Lady’s Book, 41, 377. 1850

Illustration of a common type of hair-braiding table, including bobbins and weights, Godey’s Lady’s Book, 41, 377. 1850

The equipment required for hairwork included a frame or braiding table to support the work, bobbins to maintain tension, weights to keep the work in position, a starting thread, and some sort of firm object or mold around which to braid the hair. These items were usually readily available in most middle-class households; however several dealers, including Mark Campbell in Chicago, provided specialized tools and findings through mail-order businesses, as well as catalogs and instruction manuals with extensive directions for beginners.

Hair as Material Culture

In modern times, the use of human hair as a kind of thread can seem odd or even a little disturbing. But to those living in the middle of the nineteenth century, it represented a physical manifestation of an absent loved one, one that provided spiritual and emotional comfort, the embodiment of the living and the dead. At a time of extraordinary economic change, hairwork served an important function that helped solidify the idealized expectation that middle-class woman’s place was in the home, as a maker.

Interested in reading more about hairwork? The March/April 1996 issue of PieceWork celebrates this craft.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to piecework magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including March/April 1996. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- “The Art of Ornamental Hair Work.” Godey’s Lady’s Book, 41. 1850.

- Bachman, Karen. “The Power of Hair as Human Relic in Mourning Jewelry.” In Death: A Graveside Companion, edited by J. Ebenstein. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

- Campbell, Mark. Jules and Kaethe Kliot, eds. The Art of Hair Work: Hair Braiding and Jewelry of Sentiment with Catalog of Hair Jewelry. Originally published by the author in 1875. Berkley, California: Lacis, 1994.

- Sheumaker, Helen. Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

- Wescott, Glenway. The Grandmothers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1925.

Marsha Borden is a Connecticut, USA-based needleworker and textile artist. She enjoys researching historical textile techniques, materials, and makers. Find her @marshamakes on Instagram and at marshaborden.com.