Hannah Ku´umililani Cummings Baker’s art form was Hawaiian quiltmaking (kapa). Her desire was to share her knowledge of the craft and her quilt pattern collection to perpetuate this unique craftsmanship. Hannah is my grandmother, my father’s mother. She was born on July 11, 1906, in Kapa‘a, Kauai.

Hawaiian quilting history has deep cultural roots in the islands. Before the missionaries arrived, coverings were made of a fabric called tapa, which was pounded from the bark of the wauke (paper bark or mulberry) tree. This barkcloth was then dyed and decorated with geometric block prints to use for bedding and festive clothing.

When the missionaries arrived in Hawai‘i in 1841, they brought Christianity and new ideas to the Hawaiian people. They also brought woven fabrics and steel needles; subsequently, quiltmaking was introduced.

The Hawaiian women took their new knowledge of quiltmaking and developed a unique art form that is a combination of the traditional Hawaiian barkcloth bed coverings and the New England quilting tradition.

Barkcloth (kapa moe) from the Hawaiian Islands, late nineteenth century (M.2010.106). Inner bark of paper mulberry plant. 94 × 136¾ inches. (238.8 × 347.3 cm) Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, lacma.org

The Making of Quilts

There are a number of theories as to how the patterns were created. One is that someone saw a shadow cast from leaves of a breadfruit tree onto the ground and copied it. Another is that the missionaries taught the cutting of paper snowflakes, which were adapted by Hawaiians into meaningful cultural motifs. The most likely theory is that missionaries brought appliquéd quilts and these motifs were modified by the Hawaiians.

The Hawaiian quilt has several distinct characteristics. Most of them are made using two colors, and the pattern is cut from a single piece of fabric folded in eighths. All the quilts are traditionally worked by hand, using needle and thread to create tiny, evenly spaced stitches. How many stitches are in a Hawaiian quilt? Seemingly millions! It is hard to comprehend the patience and work involved in creating these masterpieces.

Not surprisingly, traditional Hawaiian quilt designs were often inspired by nature. Flowers are especially beloved and appear most frequently in the patterns. Other designs have names that reflect things that are important to Hawaiian heritage and can be placed in three categories: nature, location, and historical significance. My grandmother Hannah’s pattern collections reflect all of the categories.

Hannah frequently told stories of her mother and great-grandmother quilting in the old days. “Never sell or give away a kapa until you make one for each member of your family. Make quilts for your daughters first and for your sons after you know your daughters-in-law. Expect your quilt to contain tears and blood and frustration; this is as it should be—a part of your spirit.” It was also traditional for a quilt to be made for a bride or the birth of a child. All seven of Hannah’s children have a quilt made by their mother. I’m fortunate to have inherited my father’s quilt.

Unfortunately, protectiveness and taboos grew up around the making of quilts. Families guarded their patterns and did not allow them to circulate. The original quilt pattern was frequently destroyed after the completion. If not, members of the family made an agreement to keep it in the family; to share outside of this close circle was kapu (taboo). Gradually, the art of Hawaiian quiltmaking almost became a lost art.

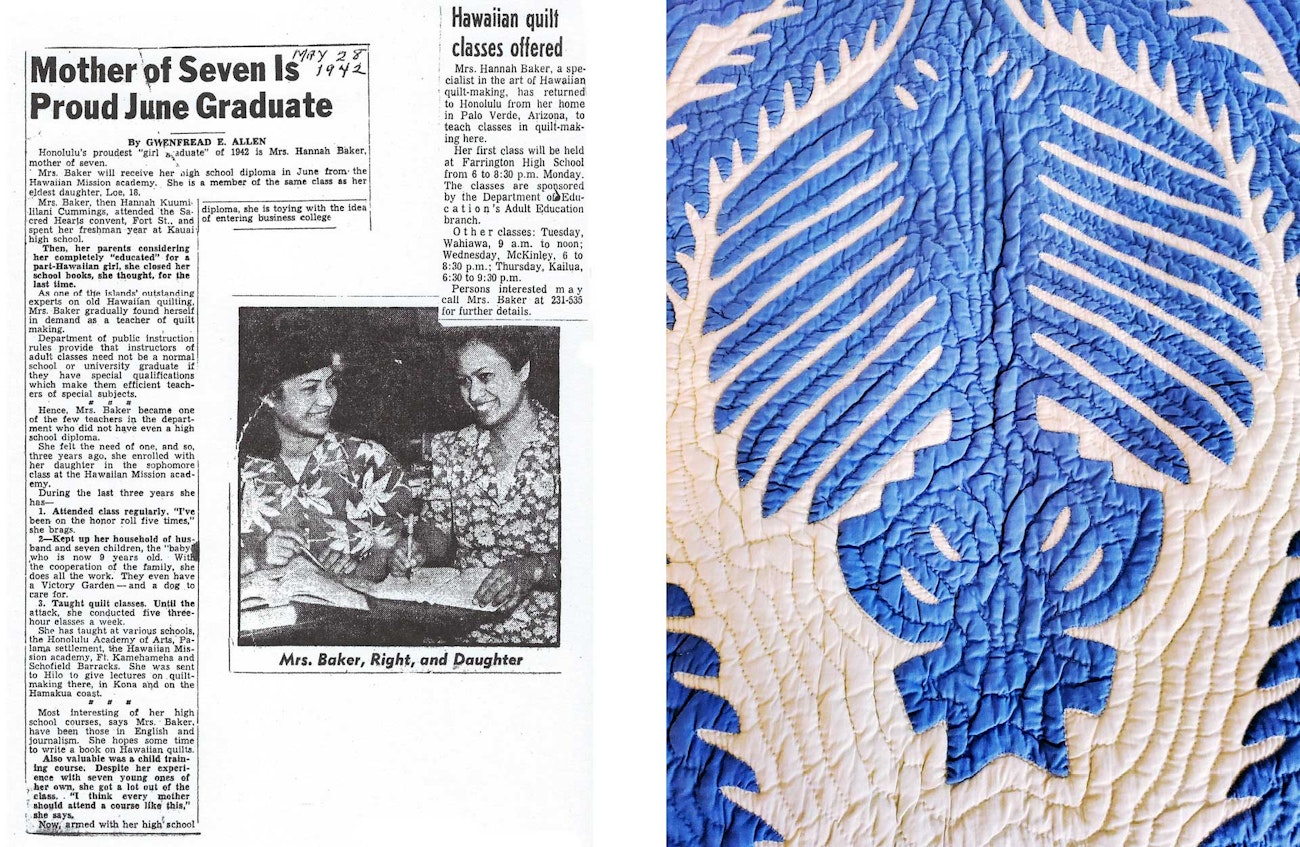

Hannah Ku´umililani Cummings Baker’s college graduation photo. Courtesy of Eileen Lee

Hannah’s Stitching

This was the state of affairs when Hannah was cutting and sewing her first kapa. Hannah was from Kauai, and her formal education had been cut off after one year of high school. At that time, she was taught Hawaiian quilting by her mother and great-grandmother. With their guidance, she became an outstanding practitioner of this Hawaiian art. When she was sixteen years old, she completed her first quilt. Her work was excellent, with tiny, evenly spaced handstitching—the most exquisite needlework.

As a young woman in the 1920s, she recognized that the Hawaiians were being pushed aside by big corporations and disease, and the native Hawaiian population was continuing to decline. Hawaiian families were dying off, and their jealously guarded quilt patterns were dying with them. Hannah had a lot of sadness about this and wanted the art to endure. Quilting was a skill in which she was talented; she was determined to share her knowledge through teaching kapa (quiltmaking) and sharing her quilt patterns.

Hannah broke tradition when she made it her mission to share her large pattern collection with students. She traveled throughout the islands with a suitcase full of antique patterns inherited from her mother and great-grandmother, as well as patterns of her own design. She encouraged students to trace as many as they liked.

Her feelings were summarized in one of her humorously accurate statements: “We, Hawaiian people, have made a big mistake. . . . We’ve hung onto our quilt patterns, and we’ve given away our land. We should have done the opposite. If we had, quilting would not be such a dying art, and we would all be walking around with rent-receipt books today.”

Hannah went back to school and graduated from high school with her oldest daughter. Later, she went on to college, got her degree, and taught elementary school. For more than 40 years, she was devoted to teaching and advocating for this fine native art throughout the islands, as well as on the United States mainland.

Left: Hannah’s family keeps clippings of her news appearances. Courtesy of Eileen Lee. Right: Detail of Kahili ‘o King Kalakaua by Hanna Ku´umililani Cummings Baker. Photo by Eileen Lee

Family Tradition

When I was a young girl, my grandmother quickly cut up some fabric and taught me how to craft a Hawaiian quilt pattern. I still have the pillow we made together. In it, I see her stitches, small and perfect, and my stitches, big and uneven. I’ve had this piece of fabric for over 50 years.

I treasure the quilt I inherited from my father. It is called Kahili ‘o King Kalakaua, which is a symbol of the ali‘i (royal) chiefs and families of the Hawaiian Islands. The symbol was acquired by Kamehameha I (1738–1819) as a Hawaiian royal emblem and used by the royal families to indicate their lineage. The feathers of small birds that were held in high regard for their religious significance were used to make the kahilis.

My father told me about memories he had as a small child watching his mother quilt. She always wore a thimble. He remembers sawhorses and devices that his father made that she used to roll the quilt so she could have access to the part she wanted to work on. These are happy remembrances.

In the early 1970s, Hannah Baker’s dream of writing a book on Hawaiian quilting was abandoned with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. With the help of her husband and sister, she taught classes for several more years but eventually had to give up teaching as well. Hannah died on April 1, 1981.

Of all the quilts Hannah made, her own favorite is a floral, a design of pikake and tuberoses. In 1978, her husband entered this—her favorite quilt—in the Great American Quilt Contest sponsored by Good Housekeeping magazine, the United States Historical Society, and the American Museum of Folk Art. Her quilt placed first in the state and took second in the national contest among 10,000 entries. Sadly, as a victim of Alzheimer’s disease, she was not aware of the honor. This prize-winning kapa was put on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington and then sent on tour for display throughout the United States and Japan. In 1999, it was included in The Twentieth Century’s Best American Quilts, edited by Mary Leman Austin. Today, this quilt is displayed at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, Hawai‘i.

Hannah’s desire to perpetuate the art of Hawaiian quilting did not end with her death; it rippled outward in many directions. Her daughter, my aunt Lillian Macedo, learned Hawaiian quilting by watching her mother. Lillian taught Hawaiian quilting for many years. In 1984, she donated the family’s collection of patterns to the Bishop Museum in her mother’s name.

It is astonishing to consider how one person, Hannah Ku´umililani Cummings Baker, could have so steadfastly and selflessly worked toward revitalizing the art of Hawaiian quilting throughout most of her life. This art was one piece of the Hawaiian culture that was precious to her, a culture that she felt was in danger of extinction. I believe that there is a little more beauty on this earth because of her. And because of her aloha, many women have participated in the art of Hawaiian quilting and many more will do so in the future.

Eileen Lee from Grass Valley, California, has a studio near her home where she teaches the arts of weaving, spinning, dyeing, and knitting. When not teaching, she spends most of her time weaving and selling her fiber art.