The year 1788 began as an unusually dull one for French fashion. “Nothing very novel for this winter,” the fashion-conscious Henriette Louise de Waldner de Freundstein, Baroness d’Oberkirch (1754–1803) complained. But inspiration for French fashion merchants was even then making its way to Paris in the form of three ambassadors dispatched by Tippoo-Saïb (1749–1799), sultan of Mysore (today the state of Karnataka) in southwestern India. The sultan had directed his representatives, who landed at the port of Toulon on June 9, 1788, to persuade King Louis XVI (1754–1793) to join him in a military alliance against their common enemy, England. The mission ultimately was a diplomatic failure, but it would be remembered as a fashion phenomenon: Although fanciful fashions and textiles à la turque and à la chinoise had been worn in France for decades, it was rare to see actual Asian dress (or Asian people, for that matter) up close.

Their timing could not have been worse politically, but the ambassadors arrived at exactly the right moment to engage the popular taste for informal, exotic, and sensual fashions. As Charles-Alexandre-François Félix, Count d’Hézecques (1774–1835), a page at the court of Versailles, observed, “These extraordinary ambassadors who arrive from the extremities of the earth always excite curiosity, and often they make history, out of the rarity of the event rather than the importance of their negotiations.” Though he never left Mysore, Tippoo-Saïb himself became an overnight celebrity in France; fashion played a dynamic role in his sudden rise to fame.

In their ceaseless quest for novelty, the fashion merchants of eighteenth-century Paris had been raiding the globe. As the Magasin des modes nouvelles commented in January 1787, “No one can deny that our French Ladies have made the Ladies of almost all the other Kingdoms adopt their fashions; however, we must admit that in almost every case they are simply paying them back. Haven’t they borrowed . . . from the Polish, the English, the Turks, the Chinese?” “The Asiatic taste,” as it was called, had a lasting influence that defied fashion’s fickle tendencies. Fashions à l’orient multiplied until the salons of Paris resembled the harems of Constantinople (or so some French critics claimed). Queen Marie Antoinette (1755–1793) had led the way. At a ball in 1782, according to observer Eliza de Feuillide, the queen had worn “a kind of Turkish dress made of a silver grounded silk intermixed with blue and entirely trimmed and almost covered with jewels. A sash and tassels of diamonds went round her waist, her sleeves were puffed and confined in several places with diamonds, large knots of the same fastened a flowing veil of silver gauze; her hair . . . was adorned with the most beautiful jewels of all kinds intermixed with flowers and a large plume of white feathers.” The event “answered exactly to the description given in the Arabian Nights entertainments of enchanted palaces.” Fashionable fantasies like these were rarely accurate, literal copies (or imported specimens) of authentic Asian dress. They might have had just one or two identifiably Eastern details—such as a sash, hanging sleeves, or stripes—or simply an exotic name. Distinctions between Near and Far East were vague or nonexistent. A variety of Asian influences might combine in a single garment, but few Frenchwomen could tell the difference. Ignorance in this case was actually a virtue, as it freed one’s creativity from the bonds of strict geographical and historical accuracy.

That changed when the Indian party—consisting of the three ambassadors, Mohammed Dervich Khan (dates unknown), Mohammed Osman Khan (dates unknown), and Akbar Ali Khan (dates unknown); two young kinsmen of the sultan; and more than thirty servants—entered Paris on July 16. While they waited for their audience with the king at Versailles, the Indians toured the theaters, parks, and churches of Paris, attracting attention wherever they went: “The morals, the habits, the costumes of these Indians were for a long time the subject of our conversations, the model for our fashions,” d’Hézecques related.

Marie Antoinette of Austria, Queen of France. Pierre-Michel Alex after Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun. French, c. 1789. Etching and wash manner, printed in blue, red, yellow, and black inks. Widener Collection, 1942.9.2430. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The artist Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun (1755–1842) saw the ambassadors at the opera and requested permission to paint their portraits. The ambassadors initially refused, citing the Islamic prohibition against representations of humans and animals; however, Louis XVI intervened and persuaded them to sit for her. Vigée-Le Brun’s portrait of Mohammed Dervich Khan is now in a private collection in France; the location of the portrait she painted of Mohammed Osman Khan and Akbar Ali Khan together is unknown. In her memoirs, Vigée-Le Brun left a description of their “robes of white muslin, scattered with flowers embroidered in gold. . . . These robes, a kind of tunic with large, turned-up sleeves, were held in place by elaborate belts.” (Vigeé-Le Brun also recorded in her memoirs, which were written years after the fact, that the portraits were painted in 1787. The ambassadors, however, were only in Paris for a few months in 1788.) The French sculptor Claude-Andre Deseine (1740–1823) produced a bust of one of the ambassadors (possibly Mohammed Osman Khan, now in the collection of the Louvre in Paris), which precisely delineates the folds of his turban and the asymmetrical fastening of his robe.

The ambassadors and their entourage reached Versailles on August 9, where according to Marc Marie, Marquis de Bombelles (1744–1822), the entire court, along with a crowd of Parisians, assembled to greet and gawk at them. D’Hézecques reported that the Indians wore costumes “composed of loose trousers and gowns of muslin or cotton cloth, fairly fine. I have not seen any gold embroideries except on their shawls, with which they wrap themselves more or less, according to the temperature. Their turbans are not as high as those of the Turks, but they are much wider.” (Elegant turbans soon appeared on the heads of fashionable Parisiennes.)

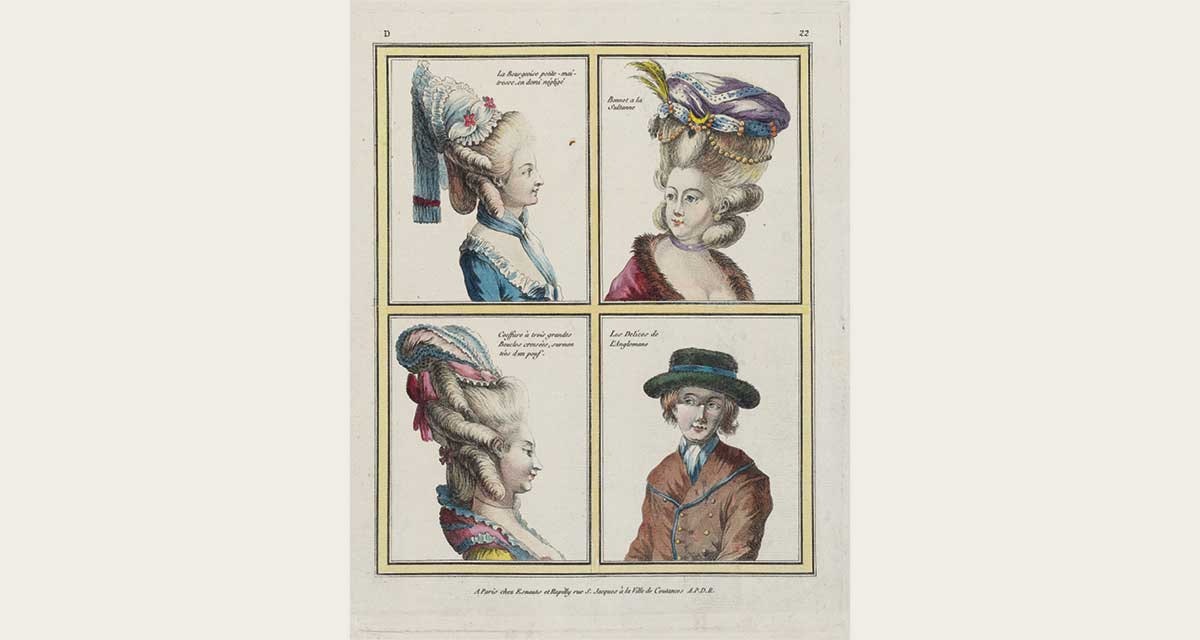

Lady in a bonnet à la sultanne, upper right. Esnauts et Rapilly. Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français. 4e. Cahier des Costumes Français pour les Coeffures en 1777 et 1778. D.22 “La Bourgeoise petite-maitresse, en demi négligé. . . .” Hand-colored engraving on laid paper. French. 1778. Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. (44.1276.1). Photograph © 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

The following day, Louis XVI received the Indian party in front of a crowd of elegantly dressed courtiers, ambassadors, and onlookers. The ambassadors presented their letters of introduction in a piece of cloth of gold (a woven fabric made with silk thread wrapped in gold), along with twenty-one gold coins, a token of profound respect in their culture. The ceremonial exchange of diplomatic gifts followed; rumors had been circulating for weeks, and many in the crowd expected the ambassadors to produce trunks full of diamonds. Instead, they presented Marie Antoinette with a gown of plain but fine muslin, lengths of “very beautiful” muslin, and a small box of pearls. The king received ornamental weapons and a large ruby, which he later had mounted on a diamond epaulette, according to Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan (1752–1822), a lady-in-waiting to Marie Antoinette. The ambassadors in turn received several lengths of silk woven in Lyons, busts of the French king and queen, and more than 250 pieces of Sèvres porcelain decorated, in deference to Islamic law, with flowers.

After their visit to Versailles, the ambassadors had an informal audience with the Countess du Barry (Marie-Jeanne Bécu, 1743–1793), who had been the mistress of King Louis XV (1710–1774). She, too, received gifts, “among others, some pieces of muslin, very richly embroidered in gold,” according to Vigée-Le Brun. When Vigée-Le Brun visited du Barry shortly thereafter, du Barry gave her one of them, “superb, with large detached flowers, of which the colors and the gold are perfectly blended.” Vigée-Le Brun kept the fabric for many years, carrying it with her when she fled the country in 1789 during the French Revolution, and finally having it made into a ball gown upon her return to Paris in 1801.

As early as February 1788, the Magasin des modes nouvelles had predicted, “Without a doubt, this year Fashion is going to travel to all the climates, all the Kingdoms, all the Provinces, and all the Countries of the world.” The following months brought fashions evoking a seemingly random assortment of countries, including Sweden, Russia, and Greece, but it was inevitable that the ambassadors’ robes would inspire fashions à l’indienne. On August 20, the magazine reported, “Tippoo-Sultan’s ambassadors are in France, and . . . they have been presented at Court. There is no doubt that they must pay their tribute to Fashion. Their arrival has been rather noticeable in Paris, and it makes an era rather noteworthy, to provoke some new fashion similar to their costume or their customs.” As anticipated, the next issue featured gowns à la Tippoo-Saïb and à l’indienne. Far from resembling the native costumes of the ambassadors, however, the new fashions were Indian in name only, honoring the ambassadors rather than imitating their attire.

Portrait of a Lady in Turkish Fancy Dress. Jean-Baptiste Greuze. French, c. 1790. Oil on canvas. Gift of Hearst Magazines (47.29.6). Image courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, www.lacma.org.

During the next two months, the magazine featured a bonnet-turban à l’indienne, a bramin belt, and a bonnet à la Pondichéri—further tributes to the ambassadors. A passing vogue for brown ribbons was even attributed to the ambassadors’ influence; as the magazine explained, “Everyone knows that cacao comes from India, and that cacao is used to make chocolate; Tippoo-Saïb’s Ambassadors have surely caused the fashion for chocolate-colored ribbons.” Chocolate had been known and enjoyed in France since the 1660s, but it took a real, live sultan to put it on the fashion map.

No one realized, as they bade the ambassadors farewell in the fall of 1788, the fate that lay ahead for them, or for France. Tippoo-Saïb did not appreciate the ambassadors’ unwitting contribution to French fashion and, as punishment for failing in their diplomatic mission, had them beheaded as soon as they returned to Mysore. And all the exotic guests and gifts in the world could not disguise France’s mounting domestic troubles, which would culminate the following year in the French Revolution, and, ultimately, the beheading of Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, Mme. Du Barry, and tens of thousands of other French citizens.

Further Resources

- Bourassin, Emmanuel, ed. Page à la Cour de Louis XVI: Souvenirs du comte d’Hézecques [Page to the Court of Louis XVI: Memories of Count Hézecques]. Paris: Tallandier, 1987.

- Buddle, Anne, Pauline Rohatgi, and Iain Gordon Brown. The Tiger and the Thistle: Tipu Sultan and the Scots in India, 1760–1800. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1999.

- Burkard, Suzanne, ed. Mémoires de la baronne d’Oberkirch sur la cour de Louis XVI et la société française avant 1789 [Memories of Baroness Oberkirch on the Court of Louis XVI and the French Society before 1789]. 1852. Reprint, Paris: Mercure de France, 2000.

- Chalon, Jean, ed. Mémoires de Madame Campan [Memories of Madame Campan]. 1825. Reprint, Paris: Mercure de France, 1988.

- Herrmann, Claudine, ed. Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Souvenirs [Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Remembrances]. Paris: Des femmes, 1986.

- Kann, Roger, ed. Journal d’un Ambassadeur de France au Portugal [Marquis de Bombelles], 1786–1788 [Diary of a French Ambassador to Portugal, 1786–1788]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1979.

- Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen’s ‘Outlandish Cousin’: The Life and Letters of Eliza de Feuillide. London: The British Library, 2002.

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is the social media manager for the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum in Los Angeles. Her work on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European fashion has appeared in Costume, Textile History, and Dress, as well as in several books and exhibition catalogs. Her book Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette was published by Yale University Press in 2015.

Originally published in Knitting Traditions Spring 2016.