Crochet buttons, olives, and balls are prominent. . . . Designers are at work to reproduce in crochet ornaments certain of the vivid colorings and startling motifs that have come to us on the wave of popularity attending the Ballet Russe, the Spanish movement sweeping around Goyescas, the Chinese influence . . . [and] the militaire with its combinings of national colors of the Allies.

—Notions and Fancy Goods, Button and Trimming Section, May 1916

Fashion forward and proud of her career as an executive secretary in Manhattan, my grandmother Sylvia Randall Bodiford could sew unlike anyone I have ever known. She was truly a couture seamstress, and every sophisticated jacket she created was replete with tailoring details: graded and pounded seams, weighted hems, and perfectly employed herringbone and hemstitching. As a little girl, I was mesmerized by the treasures in her sewing box, and it is to her credit that she didn’t flinch (much) as I pored over the exciting contents.

She helped spark my interest in anything fiber related, and I was excited when someone taught me how to crochet because I knew I had seen a hook in her basket. When I showed off my newfound skill, I asked her if she could teach me more. She was shocked and said resolutely, “I don’t crochet—I only know how to sew.” When I pointed to the slim metal hook in her workbasket, she said “Oh, oh no, that is for sewing,” and proceeded to show me the tiny chain stitches she made to secure the hang of a lining, a delicate button loop at the top of a jacket, loops to keep a self-belt anchored, a length with snaps on either end to corral a wayward lingerie strap, and a neat row of crocheted buttons or frogs on a blouse, all constructed with intimidatingly even stitches and fine thread. Self-taught in her teens from reading old how-to books and magazines, she genuinely believed that she didn’t know how to crochet.

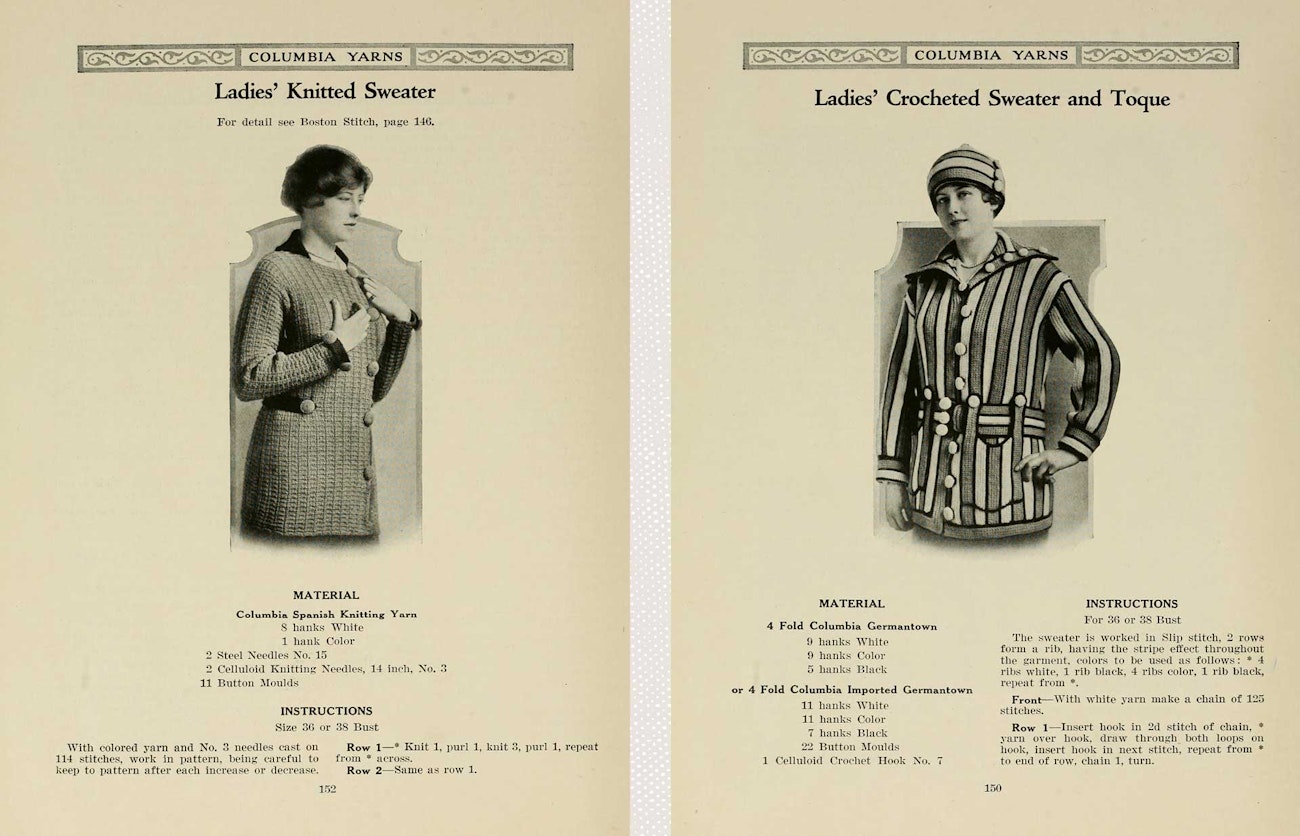

Left and Right: The Columbia Book of Yarns, 1916. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Needlework on the Move

Most immigrants to the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century came from Ireland, Germany, and Britain—cultures that valued fine needlecraft. They brought crocheting and lacemaking skills to a country whose women excelled in practical handicraft, such as knitting, sewing, weaving, and quilting. The beauty of crochet was that it could be made to imitate costly lace, it was inexpensive, and it was easily taught. By the dawn of the twentieth century, more women joined the workforce, and they had neither discretionary time nor money to spend on painstakingly re-creating European lace. However, they could proudly don homemade outfits embellished with the same accessories that the newspapers and magazines claimed to be de rigueur Parisian fashion.

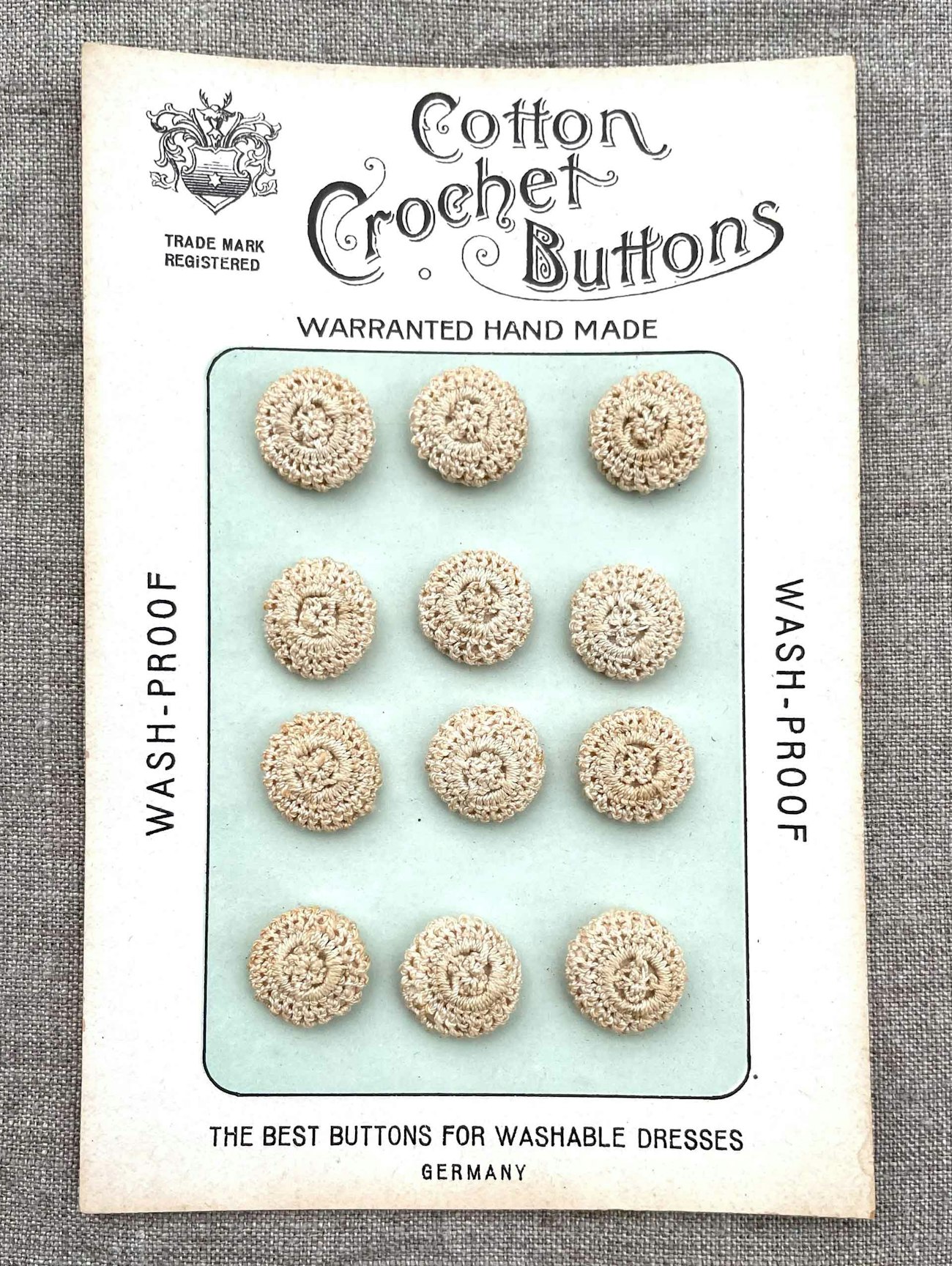

The unique sculptural quality of crochet lent itself readily to the creation of haberdashery items. Novelties such as crochet buttons, buckles, ties, and frogs were firmly on trend in 1916, and the newly created button section of the trade journal Notions and Fancy Goods was laden with advertisements by crochet button vendors and glowing descriptions of the crochet craze that had taken over the art embroidery, fashion, and home decor industries.

By the middle of World War II, this comprehensive trade journal reflected the many societal changes that were impacting fashion. Ads promoting crocheted belts and buckles for tennis and golf clothing as well as swimwear were meant to appeal to a growing sporty set. The costly and high-maintenance ruffled lace and voluminous fabric from previous years made way for more economically appropriate ensembles. Skirts paired with fitted jackets, sweaters, or tunics were more suitable for both working women and those who labored at home while their loved ones were away in the armed services. Structured and simple, they were a perfect foil for orderly adornment.

A hand-crocheted collar, buckle, or decorative row of buttons could elevate an outfit—and a mood—with minimal cost or effort. In the “From Paris” section of Harper’s Bazar in 1916, writer Emilie de Joncaire pondered a garment from the atelier of Callot Soeurs: “What could be smarter than a three-piece suit of cherry valerdine . . . [trimmed with] innumerable crochet buttons”—a nice endorsement for a notion that was easy to make at home. A little time with some thread and a hook and a working-class crafter could adorn her clothing with the same sophisticated touches sported by the leisure class.

Military-style closures were newly popular on ladies’ tops. Rows of buttons or frog closures on tailored jackets gave an aura of strength and authority to women, which was a fitting reflection of the times. In the 1910s, Alva Belmont, socialite and former wife of William Vanderbilt, formed what would become the National Woman’s Party with suffragist Alice Paul. The group organized the first-ever picket march in front of the White House, and the Nineteenth Amendment was later ratified in 1920. Contemporary patterns aimed at the home stitcher also featured pairs of crocheted buttons with cords wrapped around them to mimic the passementerie clasps from regimental coats of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

German-made buttons sold as “the best buttons for washable dresses.” Ninteenth century. Photo by Kate Larson

Button Trade vs. Homemade

It is easy to perceive a crochet fastener as a folksy thing, easily made by hand and a giveaway as to the home manufacture of the garment, but in fact, that was not the case. Crocheted buttons were a commodity, and their manufacture and sales were detailed in government trade reports. At least one newspaper column of the time suggests that the cost of making a button at home would defray the price of expensive premade crocheted buttons, and one article sent in by a reader suggests economizing by placing leftover scraps of lace over fabric buttons to imitate crochet.

Crochet thread had many advantages—it was both affordable and accessible. Button-makers suffered during this period, as war and an embargo meant that there was a scarcity of dyestuffs—natural materials such as logwood and the aniline dyes that were still fairly new. The ability to make colored cloth and notions diminished. Most of the crochet thread on the market was white, which could be used to match almost anything, filling the gap in the button industry. Eventually, the burgeoning popularity of crochet—steadily rising through the Victorian era—created a logjam, and thread manufacturers could barely keep up with the demand. Domestic production of cotton and silk fiber gave rise to many new mills.

Desperate to keep the momentum going, these companies vied with one another for a share of the customer base. The widespread use of rotogravure prints meant that mills were able to create pamphlets full of photographs to entice new customers and to market their wares. Pattern books proliferated—some with faithful reproductions of European trends and some with original designs ranging from excellent to outlandish. Knitted and crocheted pieces with handmade laces, buttons, and frogs were abundant, and often it was assumed that a reader would know how to cover a button with single crochet, so only scant, if any, direction was given.

The rise of news syndication services afforded stitchers in small towns in the Midwest the same up-to-the-minute style columns and patterns to read as the fashion journals in major cities. Proclamations such as one that the newest ensembles for summer would be graced with crocheted buckles were undoubtedly met with enthusiasm by the home stitcher. With inexpensive materials, crocheters could produce all manner of clothing and home decor items, from gossamer to robust, and, improbably, they could even sculpt dimensional items, such as brimmed hats and starched baskets. By and large most of the crochet fasteners were washable, although some of the patterns of the time called for the crochet to be worked over a foundation of cardboard. The instructions recommended that the buttons be removed before laundering, which was a reasonably common practice then, although one that was probably not met with much favor.

Cotton and silk crocheted closures were featured on every type of fabric, clasping front bands of furs and tailored wool suits, ornamenting linen dresses, sprinkled daintily among crocheted lace handbags and gowns, and adorning knitted cardigans. They were utilitarian and versatile. For a busy woman, a handmade crochet lingerie clasp, a delicate chain to lace a lingerie yoke, a belt buckle, a beauty pin, a button, or a frog could be a quick-to-create gift or element of style.

It took many years as a novice crocheter before I attempted to use a tiny metal hook, and I was always daunted by how time consuming thread projects were to make. Early twentieth-century crocheted fasteners are a great foray into delicate thread crochet, as they are timeless, functional, and quick to make at the same time. My grandmother’s judicious deployment of thread crochet buttons and buckles proved that a simply wrought detail can elevate any piece of clothing. And, to use one of her signature phrases, “They are just stunning.”

Resources

- Button and Trimming Section. Notions and Fancy Goods 50, no. 5 (May 1916): 52–72.

- De Joncaire, Emilie. From Paris. Harper’s Bazar 51, no. 9 (September 1916): 60–67.

- Schumacker, Anna. The Columbia Book of Yarns. Philadelphia: Manufacturers of Columbia Yarns, 1916.

Pat Olski is a New Jersey–based needlecraft designer, writer, and instructor who loves historic techniques and old needlework books. Her book Crafting Thread Jewelry teaches heritage Dorset button techniques; and her history, reference, and project-based title, Creating Dorset Buttons, will be published in early 2022. Learn more @yarnwhirled on Instagram and Facebook and at yarnwhirled.com.

This article originally appeared in PieceWork Winter 2021.