In 1921, Celia Wiggins was born in the village of Shafton, South Yorkshire, as England recovered from World War I. She grew up in a time of economic depression, and unemployment in her village was high.

Her father, a coal miner, was killed in a mining accident when she was nine years old. There was almost no work available for women in a small village at that time, so Celia’s mother raised her and her three younger siblings by cobbling together a pension from the government, a pension from the miner’s association, and living in housing provided by the local council. Celia was lucky to be able to attend grammar school, escaping the only other choices for a young woman at the time: going into service as a scullery maid as Celia’s sister did, or competing for one of very few jobs in a shop.

It isn’t surprising that someone growing up in such circumstances would learn thrift and reuse as second nature. However, even within Celia’s family, her native cleverness and talent for working with her hands were something special. Celia’s mother did not have a gift for being economical, so Celia learned from her grandmother—how to get the maximum life out of a garment, how to save and reuse buttons and zippers, how to “sides-to-middle” worn sheets, and how to remake pieces of garments into entirely new ones.

Left: Celia (right) during World War II. Right: Celia Wiggins Sanderson (1921–2016), as a young woman. Photos courtesy of Olwen Sanderson

The Make-Do and Mend Generation

Then came World War II. In the midst of the severe rationing in Britain, particularly of clothing, fabric, and yarn, Celia practiced the kinds of thrift common to many around her in her village, such as knitting pullovers from raveled worn-out sweaters. In the early 1940s, the government launched its Make Do and Mend campaign. This may have inspired Celia’s school, as they included a remake project in one of her domestic-science classes. She chose to make gauntlet gloves from a fur collar that she bought from a stall in Barnsley market. Warm gloves were a welcome comfort when she waited for buses in the cold Yorkshire winters. As she grew into adulthood, Celia came into her own as a skillful and creative needleworker. Others said of her that she could make her sewing machine sing. Ever practical in the rest of her life as well, she attended Bingley Teacher Training College in West Yorkshire to allow her to get a good job as a teacher.

When she met her husband, Kenneth Sanderson, she recognized in him a similar spark of intelligence and a similar drive to be frugal. A particularly fine example of her wartime reuse was inspired by his quick thinking. Kenneth was a sergeant in the Royal Air Force, and one day he noticed the heavy wool curtains in the aerodrome’s officers’ mess being taken down to be replaced. Kenneth, who had a cynical sense of humor, used to joke that he could have walked out of there with anything—including a Lancaster plane, if only he could have fit it under his arm. The curtains did fit, though, and he took them home to his wife.

In these cast-off curtains, Celia recognized exactly what she needed; she now had her teaching certification, but no formal clothes to wear to her first job. Rationing meant no fabric was available. The dress she created out of the wool curtains was scratchy and uncomfortable to wear, but she paired the dress she made with a silk blouse from her school uniform. Through this joint effort, Celia was able to start her new job impeccably turned out. During the wartime rationing, she also made underwear and nightgowns from parachute silk that likely came home under her husband’s arm as well. That silk stayed with her. She used it to line one of her daughter’s coats, and some remained in her fabric stash at the end of her life.

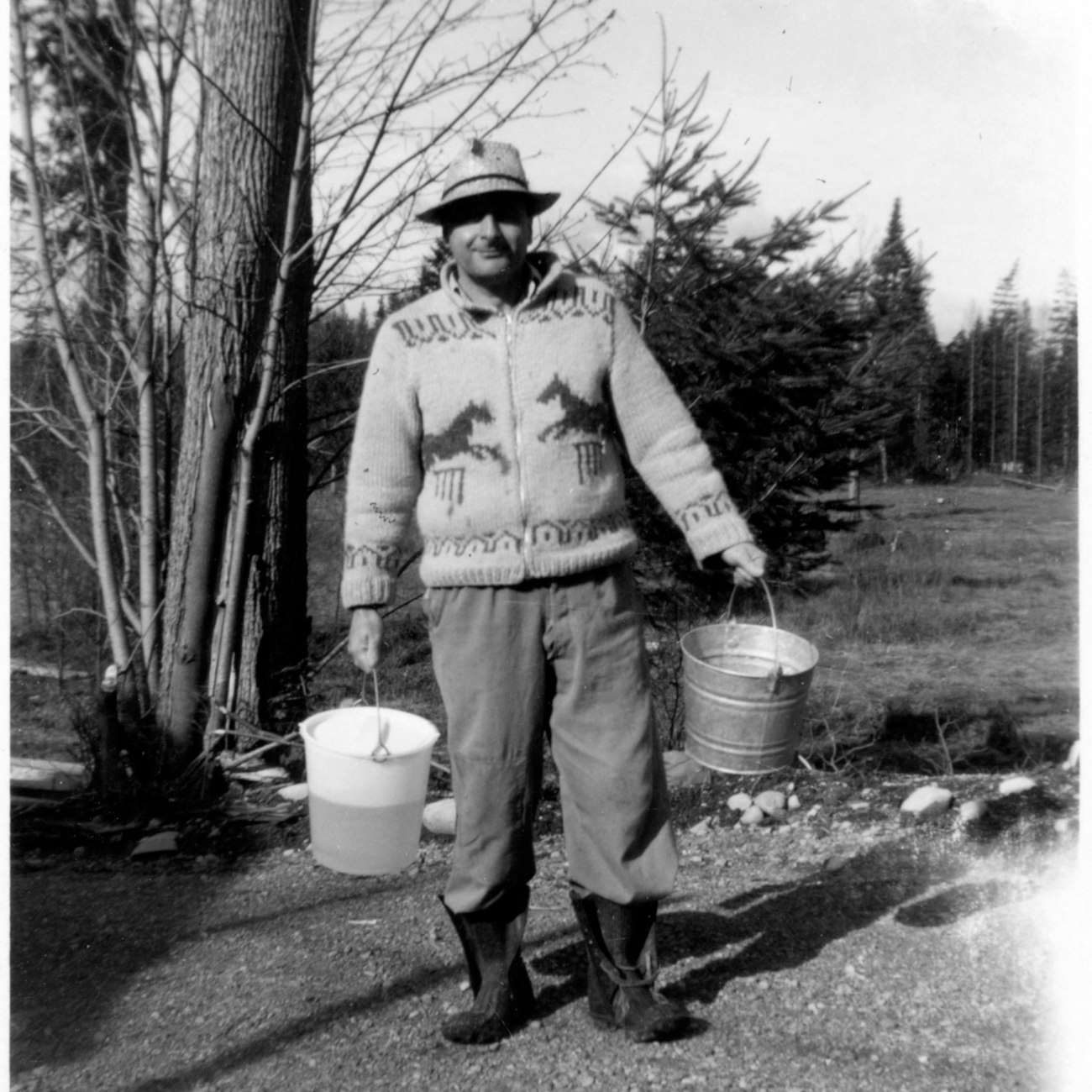

Kenneth wearing Celia’s Cowichan-style sweater at the farm on Vancouver Island. Photo courtesy of Olwen Sanderson

A New Life

Rationing in Britain eased eventually, and in 1953, Celia and Kenneth emigrated to British Columbia, Canada. At that time, the arduous journey stretched from a steamship ride to Montreal, to crossing the continent by train, and ended with a ferry ride to the island. Kenneth dreamed of owning arable land so he and his family would never be subject to rationing again. However, times remained hard for the couple and their two daughters as, in those days, no one was allowed to take much money with them out of Britain when they emigrated. Worse, the teaching job Kenneth had been promised was not available when they arrived, and there were problems with transferring his teaching certification to Canada.

Although within a few years she and her husband did purchase land and their savings in the bank grew, Celia never gave up the skills she’d learned in her youth, both of handwork and of economy. Her central philosophy was that something could always be done to find the good in a bad situation.

The land Celia and her husband bought in Canada was near the small village of Cobble Hill, on Vancouver Island. The natural setting and friendly neighbors gave Celia the raw materials she needed to express her talents. When she wanted buttons for an Aran sweater she’d knitted and a particularly nice wool coat, she convinced a neighbor to give her an antler from a deer he’d hunted. She cut rounds from the antler and finished them into buttons herself.

Another neighbor kept a few sheep and gave her a fleece, as he didn’t know what to do with it. Celia had heard that some of the Cowichan First Nations women rolled their yarn rather than spinning it, an ancient technique often called thigh spinning that requires no spinning tools. Thigh-spun yarn is created by drafting teased fiber in one hand as the other hand inserts twist by rolling the palm of the hand against the thigh. After Celia had washed and carded her wool, she met with a woman from the Cowichan Tribes to learn how to create yarn without a spindle or spinning wheel. Celia adapted the traditional technique, rolling the teased wool on a brick, while inserting twist wearing an old leather glove. She knitted her resulting yarn into a Cowichan-style sweater that her husband wore for many years.

The Gift of Creative Economy

When her two daughters were young, Celia sewed most of their clothes. She would put a large tuck of fabric above the hem of the dresses that could be let down as they grew. If the fold line showed, she used a length of rickrack or tape over the line to transform it into part of the dress’s design. She never bought the rickrack or tape new, of course—she would buy partial spools at thrift stores to build a stash.

Celia’s making and mending stash filled a room in her home’s daylight basement. At the time of her death, her sewing room still held her top-of-the-line electric Singer sewing machine, purchased in the 1960s to replace the treadle Singer her husband gave her just after their marriage; an ironing board, always down and ready to use, with a tailor’s ham she made herself; old chocolate boxes full of buttons; bags of zippers, bias tape, and elastic; boxes of sewing patterns and fabrics; a drumcarder for preparing wool; and so many useful oddments.

When her elder daughter, Olwen, was four or five, she stained the skirt of one of her dresses, so Celia used some fabric scraps to make a pocket shaped like a tulip flower over the stain and used bias strips to form the tulip’s stem. As her grandmother had taught her, Celia also taught creative economy to her daughters: Olwen takes great pleasure in knitting, crocheting, cross-stitching, and sewing, and accumulates materials just as her mother did. When Olwen’s own elder daughter, Rhiannon, started cross-stitching, Olwen hardly had to buy a single new skein of embroidery cotton—she assembled the dozens of colors needed for the pattern from a stash she’d amassed secondhand.

When her daughters reached adulthood, Celia’s efforts didn’t lessen. And later in her life, Celia seemed to take on projects purely for the challenge. Once, Olwen bought a secondhand sweater that developed a large hole in the front as soon as it was washed. Despite Olwen’s protests, Celia offered to knit a patch into the hole. She couldn’t find yarn in a color with a close enough match to make the repair invisible, so she began a meticulous renovation that involved sourcing repair yarn by raveling the cuffs and reknitting them in a similar yarn, removing the hem, reknitting the section with the hole, and grafting the whole thing back together. When she was done, the sweater showed no sign of either the hole or the repair, and Celia was pleased to have set the sweater to rights and to have a usable garment again.

In addition to Celia’s memorable one-off projects, there was also the ongoing, daily mending that shaped the lives of many of her generation. Celia’s husband wore heavy wool farmer’s socks, so there was always an endless supply of heels in need of darning. She kept a basket of them next to her chair in the living room so she could work on them of an evening. Even at the end of her very long life, when she had trouble remembering things, Celia had that basket beside her chair and often a knitting project in her hands. Reuse and repair had begun as a necessity when she was a child, but for her, they grew into a way of life.

Left: Sweater with antler buttons that Celia cut herself. Middle: A nightgown Celia made out of parachute fabric following World War II. Right: Cowichan-style sweater Celia made for Kenneth.

Sides-to-Middle Sheets

“Pains should be taken to prevent linen falling into rags until the utmost wear has been exacted. [When] the middle of a sheet begins to feel at all thinner than the other parts, it is time to ‘turn’ it. This is done by simply cutting the sheet in half and sewing together the outside selvages. The newly made seam will then be the middle of the sheet. The sheet, if not much worn, will require no further alteration for a long time. If, however, the wear has been considerable, side pieces should be let in to the extent, and several inches beyond, the worn places. The sides must then be hemmed or sewn in the ordinary way. When, after a time, the ‘turned’ sheet wears thin in the centre, instead of patching it, as some people are apt to do, it is better to sew the ends together, making the ends of the sheets now the middle.”

— Cassell’s Household Guide (1869)

Interested in learning more about mending? This article and others can be found in the Fall 2020 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Fall 2020. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Cassell, Ltd. Cassell’s Household Guide: Being a Complete Encyclopœdia of Domestic and Social Economy. Vol. 4. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1869.

Rhiannon Held is Celia’s elder granddaughter. She still cross-stitches often in adulthood, as working with her hands is a welcome rest from the mental effort she puts into her avocation—fiction writing. She is the author of multiple published speculative-fiction novels and short stories.

Olwen Sanderson is Celia’s elder daughter. She is a retired family-practice physician who knits prayer shawls and practices economy in Portland, Oregon.

Originally published November 23, 2020; updated September 16, 2024.