For over a hundred years, women in the Polish village of Koniaków have crocheted stunning lace designs in fine cotton thread. Despite its beauty and uniqueness, Koniaków lace flew under the global radar until 2003, when a group of lacemakers began crocheting risqué lingerie instead of doilies. But crocheted undergarments are only a small part of the story of Koniaków lace. Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut, who heads the Koniaków Lace Center and Museum, sums up her community’s lacemaking tradition in three words: “Art. Tradition. Passion.”

The Art of Koniaków Lace

When you first see Koniaków lace, you may think of snowflakes, intricate flowers, or stars. Worked in white or ecru cotton thread with delicate lines and swirling motifs, Koniaków lace has an ethereal feel. The most important thing you need to know about Koniaków lace is one of the most astonishing: Koniaków lacemakers do not use templates or patterns.

Each lacemaker creates her own motifs, which are often based on nature, and incorporates them as she works the larger piece. For example, lacemaker Zuzanna Ptak was inspired by how the sun’s rays shone from around a nearby mountain peak; now she frequently designs flower motifs surrounded by “rays.” This connection to the surrounding natural world underlies the lacemakers’ work and gives it special meaning.

Once a crocheter finishes the individual motifs, she joins them together using “spiders,” which are usually circular or star-shape geometric structures. This unusual method of design and construction means that no two pieces of lace are exactly alike. Like nature, the lace has small imperfections that only add to its beauty. Though created extemporaneously, designs are marked by their attention to composition. As Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut describes it, “Each pattern is symmetrical and even countable. There is no randomness here.”

Traditionally, Koniaków lace is worked in white or off-white fine cotton thread using fine-gauge hooks. Today’s renewed interest in using Koniaków lace for less traditional garments has led some younger designers to use colored threads, especially black. It’s unlikely, however, that darker threads will supplant white or cream. It’s significantly harder to crochet such intricate designs using dark thread. That means that lacemakers can’t work on dark-colored projects all day as they can with light colors, particularly older makers with less accurate vision.

Koniaków lace has a deep, almost visceral connection to place. Of course, this is partly a function of its design focus on the natural world surrounding its makers. It may also relate to the way its techniques are taught—knowledge is passed on person to person, usually by mothers, neighbors, or friends. Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut observes that even though some techniques are available online, many crocheters outside Koniaków cannot duplicate the designs—they use heavy connecting lines, or they lay out motifs incorrectly. “Lacemaking knowledge,” she explains, “will not come naturally without being here and living our culture. That’s the magic of our lace.”

Dreamcatcher in Koniaków lace with pom-poms. Photo courtesy of Centrum Koronki Koniakówskiej, permission granted by Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut

Koniaków Lace Traditions

While we can’t point to an exact time when Koniaków’s lacemaking tradition started, we do know that Koniaków lace is about a century and a half old. We also know that the technique has its roots in the region’s folk costume.

Polish highlander women traditionally wore collared shirts with puffy sleeves, skirts, aprons, and a bonnet or mobcap called a czepiec. A portion of the cap, often made of netting, covered the wearer’s forehead, framing her face. Historical documents show that crocheted lace adorned the front of these caps by the early 1880s.

Mobcaps were worn by married women and played a cultural role in village life. As part of wedding festivities, other married women would remove the bride’s flower crown, replacing it with a cap—a symbol of being welcomed into the community and the responsibilities of married life. Like her wedding ring, Ligocka-Kohut explains, the cap “accompanied her from the wedding ceremony until the end of her life. Lacemakers who could not afford a mobcap crocheted it by themselves. Women tried to stand out, so they experimented with motifs.”

It didn’t take long for the distinctive type of lace to catch on. Soon, women added lace inserts to blouses and shirts and used crocheted lace to adorn ecclesiastical garments and altar cloths. Historical documents show that lacemakers produced crocheted doilies by 1906 or 1907. In time, hotel owners and shopkeepers sought out lace napkins, tablecloths, and doilies. By the period between world wars, Koniaków lace was highly sought-after by businesses and a growing urban bourgeois class. In addition to doilies and table linens, items such as lace curtains, bags, collars, and stockings became popular.

The vitality of the lacemaking trade in Koniaków was deeply affected by the Second World War and the subsequent formation of the communist Polish People’s Republic in 1947. Enter a master lacemaker named Maria Gwarek.

Left: The Koniaków Lace Museum in Koniaków, Poland. Right: Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut with children at the Koniaków Lace Museum. Photos courtesy of Centrum Koronki Koniakówskiej, permission granted by Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut.

A Passion for Koniaków Lace

The story of Koniaków lace wouldn’t be complete without the individual women whose passion for the craft translated into a fierce determination to keep it alive, like Maria Gwarek. Sometimes called “the mother of Koniaków lace,” Gwarek was born in 1896 and had a crochet hook in her hand from the time she was a little girl. As an adult, she was recognized as a local lace authority.

Gwarek was not just a master lacemaker, however; she was also a social activist. In 1947, Gwarek founded a cooperative for Koniaków lacemakers. While the Koniaków Lace Collective was a way to preserve this beautiful craft, it was also intended to create socio-economic opportunities for Koniaków artisans. A pastime that once was used as a break from physical labor or as a sideline for some extra income became a respected, paid profession.

The Collective employed women as lacemakers and instructors and provided them with a way to support themselves. At the same time, it fostered the growth of the art by sponsoring exhibitions and competitions, developing new patterns, and finding markets for finished items.

In an odd twist, the dreary day-to-day life in post-war Poland inspired a fresh interest in genuinely Polish items, from fabrics to sculpture to pottery.

After World War II, the communist People’s Republic of Poland (PRP) controlled all Polish industries, from autos to food to health care. In the late 1940s, PRP agencies decided to extend state protection to folk art and formed the Folk and Art Industries Headquarters in 1949. A state-owned chain of shops called Cepelia began selling folk art, including Koniaków lace. Working with Cepelia shops, as Maria Gwarek did, provided a way for a local craft to be seen and admired all over Poland. Cepelia shops were successful for decades but saw a decline in popularity once the Polish economy switched to a capitalist structure in 1989.

After the untimely death of Maria Gwarek in 1962, her daughter-in-law Zuzanna took the helm of the Koniaków Collective. Zuzanna was a lifelong lacemaker known for the exquisite composition of her work. Zuzanna and her husband Erwin continued to run the Collective; they also collected examples of lace created by master crocheters. In 1980, they founded the Memorial Room of Maria Gwarek, displaying the oldest examples of Koniaków lace as well as unusual lace items. Zuzanna carried on the work of the Koniaków Collective until her death in 2015.

View on Koniaków from the Ochodzita Mount. Photo by Kamil Czain´ski, courtesy of WikiCommons

Spurred by an Unlikely Source: The Renaissance of Koniaków Lace

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, interest in doilies and other traditional lace products waned. Fewer women were learning Koniaków techniques, and the lacework was in danger of becoming a bygone art. And that’s where the lingerie came in. In 2003, some Koniaków lacemakers took a bold step: they began using traditional Koniaków methods to produce undergarments, including thongs and G-strings. From a marketing perspective, the initiative made sense. Lingerie always sold briskly and the media attention—with headlines like “Lace and Licentiousness” and “Veruschka’s Secret”—drew new attention to the village’s lacemaking heritage.

The decision to branch out into less traditional products divided lacemakers. Some felt that using traditional motifs for items like lingerie was a betrayal and an insult to an almost-sacred art. More pragmatic crochet artists took the change in stride. After all, smaller items like G-strings took less time to make and sold better than, say, large tablecloths or doilies.

The controversial shift to lingerie-making was just the beginning of a larger renaissance for Koniaków lace, driven in large part by Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut. Growing up in a nearby village, Lucyna saw her grandmother in Koniaków make lace. It wasn’t until Lucyna began her ethnology studies that she came to appreciate how uniquely valuable her heritage was.

A whirlwind of energy, Lucyna has made the promotion and continued production of Koniaków lace her life’s work. In 2019, she opened the Centrum Koronki Koniakówskiej (the Koniaków Lace Center). The Center includes a museum, a shop selling genuine Koniaków lace products, and an educational space for workshops and classes. Although she does not make lace herself, she has taken a three-pronged approach to preserving Koniaków lace: increasing awareness of its beauty, using modern applications to challenge old notions about lace, and providing a space where makers can collaborate and learn from each other.

One of Lucyna’s projects was a 2018 collaboration with Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons. Kawakubo was interested in working with global folk artists and approached the Koniaków lacemakers. Although the designer didn’t quite appreciate that Koniaków lace was genuinely slow fashion—it can take a lacemaker hours to perfect just one small motif—she was intrigued enough to order three hundred rectangular lace tablecloths.

Lacemakers came together to produce them in record time. Kawakubo incorporated the lace into a 2018 wedding dress presented at Paris Fashion Week. The publicity and appreciation of the lacemaker’s art led Lucyna to realize the importance of taking Koniaków lace in new directions.

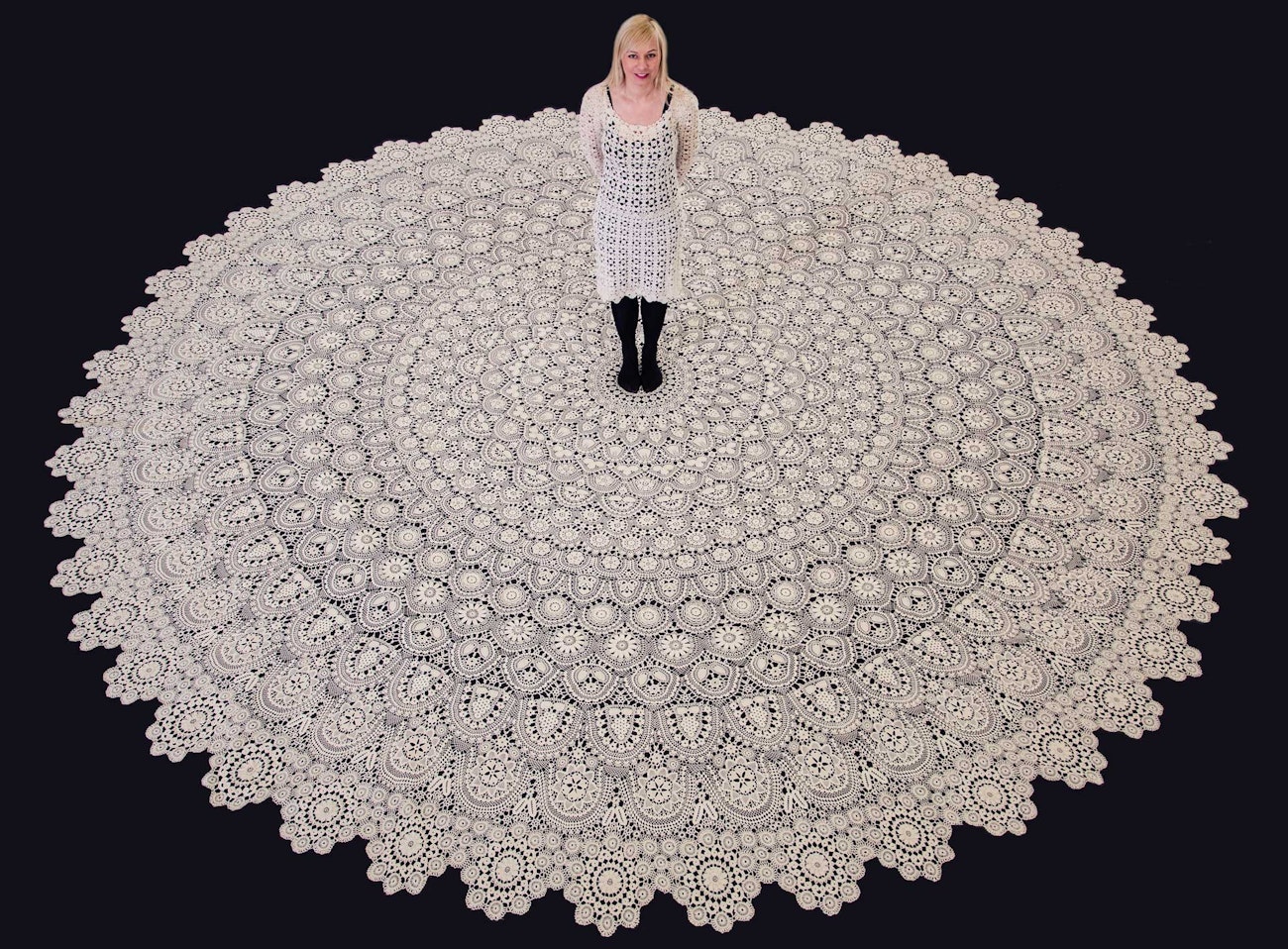

Some other recent projects include the creation of the world’s largest Koniaków lace—a doily measuring 16½ feet across, made from eight thousand individual pieces over a five-month period. The lace was certified by the Guinness Book of World Records, introducing a new audience to the traditional craft. Another success: a display of crocheted dresses, titled “Flowers of Koniaków,” which was on display at the Polish Pavilion of the 2020 Dubai Expo.

The Center has also begun a new initiative to create Koniaków lace from wool, specifically the wool from local sheep. Central to all of these projects is Lucyna’s vision: “We want to encourage [people] to play with Koniaków lace, get to know it and even fall in love with it, to carry this tradition into the future.”

Largest Koniaków lace doily 2013. The piece measures 16½ feet in diameter and took five months to complete. Photo courtesy of Centrum Koronki Koniakówskiej, permission granted by Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut

Interested in reading more about moonlight makers? This article and others can be found in the Spring 2024 issue of PieceWork.

Also, remember that if you are an active subscriber to PieceWork magazine, you have unlimited access to previous issues, including Spring 2024. See our help center for the step-by-step process on how to access them.

Resources

- Barnat, Gabriela. “Meet the Head of Polish Cultural Center Lucyna Ligocka-Kohut,” gabrielabarnat.com/stories/meet-the-head-of-polish-cultural-center-lucyna-ligocka-kohut.

- Centrum Koronki Koniakówskiej (Koniaków Lace Center), centrumkoronkikoniakowskiej.pl.

- Czajor, Paulina. “Koniaków Lace,” Polish Fashion Stories, polishfashionstories.com/we-love-1/2021/11/23/koniakow-lace.

- Jasin′ska, Joanna. “A stitch in time: World Famous Lace Makers Get Grant to Keep Their Skills Safe for Years to Come,” The First News, March 7, 2020.

- Sznajder, Anna. Polish Lace Makers: Gender, Heritage, and Identity. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Carol J. Sulcoski is a knitting author, designer, and teacher. She has published seven knitting books, including Knitting Ephemera (Sixth & Spring), which is full of knitting facts, history, and trivia. Her articles have appeared in publications such as Vogue Knitting, Modern Daily Knitting, and Noro Magazine, as well as on the Craft Industry Alliance website and elsewhere. She lives outside of Philadelphia and teaches at knitting events, knitting shops, and guilds. Her website is blackbunnyfibers.com.