Many of us treasure special needlework tools that have come down to us from our ancestors, perhaps an unusual bone crochet hook that our mother used or handcrafted knitting needles inherited from a great-aunt. In my case, they are wooden tatting shuttles that my grandfather Anastasius “Tom” Nicolaides (1890–1966) made for my grandmother Charlotte Sedwick Nicolaides (1901–1984).

The lacemaking technique of tatting began in the sixteenth century as an elaboration of simple knotting, and it evolved over the next three centuries. At its peak in the nineteenth century, tatting embellished the edges of cuffs, collars, and undergarments, as well as constituting the fabric itself of such three-dimensional textiles as baby bonnets, purses, and booties. Needlework publications were filled with patterns for this particularly feminine art—tatting was a graceful pastime, its swift, rhythmic movements resulting in yards of beautiful lace.

Grandma learned to tat in the 1920s. Fifty years later, she tatted like a machine. Without looking at her work, fingers flying, she turned out yards of edgings that she rolled into a ball in her lap, securing her work with a giant safety pin. Her favorite wooden shuttles, crafted by Grandpa, ticked rhythmically in a soothing, hypnotic tempo.

She tatted sweet, simple, blue-and-white edgings to adorn my nightgowns; she also tatted vivid, variegated aqua and hot pink antimacassars for her 1940s-era overstuffed chairs. I find the bold colors and three-dimensional designs of the latter pieces particularly fascinating and amusing.

Shuttles from the author’s collection and examples of Charlotte Sedwick Nicolaides’s tatting.

Grandma was a member of the International Old Lacers Inc. (IOLI, an international organization for lacemakers), and she bought books, experimented with patterns, and filled notebooks and cards with original patterns. She had dozens of balls of DMC thread in wondrous colors.

When I was eight years old, Grandma sat me down with one of her wooden shuttles and size 80 thread and began teaching me to tat. She was strict. No snapping off of mistake-ridden thread was permitted: I was to pick out my mistakes with a pin. If I tried to break off a ring that was not going well, perhaps coughing to cover the snap, she’d say, “I heard that.” There was no fooling Grandma.

Slowly, I learned to tat. I began collecting patterns from books and shared my limited knowledge with schoolyard friends. Forty years later, I am still tatting and using shuttles that Grandpa made sixty years ago. They suit my hand as they did Grandma’s.

A native of the remote town of Rapsani, nestled on the olive-laden slopes of Mount Olympus in Greece, Grandpa immigrated to Monmouth, Illinois, in the 1910s. I don’t know how or when he learned to make tatting shuttles. As a child, I used to like to go to his basement workshop and play with the paper templates that he used to rough out the shuttles before carving them into boat shapes.

Shuttles from the author’s collection, vintage thread, and examples of Charlotte Sedwick Nicolaides’s tatting. The thread, including a ball of DMC Cordonnet Special size 150, belonged to Charlotte Sedwick Nicolaides.

Grandpa used a unique two-post form of his own design (most shuttles have a single post) and wood-burned his initials, “AN,” on the interior of his best work. His shuttles ranged in length from less than 1 inch (2.5 cm) to more than 3 inches (7.6 cm). The small ones were perfect for delicate threads and small projects, the larger just right for sturdier threads and yardage or for larger hands.

Over the years, Grandma gave me several of Grandpa’s shuttles. When she died, my cousin Vicky Saeger and I inherited the rest of them—I assumed. I began to supplement my collection with shuttles by other makers. Not having a lot of money to spend on them, I was content with acquiring the occasional pumpkinseed shuttle on eBay or a special commemorative from a local antique market or lace workshop.

One day about ten years ago, I saw a wooden shuttle on eBay that was unmistakably one of Grandpa’s. It had the same two-post design, and the initials inside were his. Part of my past was out there on the Internet, part of my life, part of my family’s history.

The seller told me that besides the one on eBay, she had sixteen more similar shuttles that she had obtained at an estate sale in Oregon. I arranged to purchase each of the remaining shuttles; I felt that the seller understood my longing and need for these family artifacts and history.

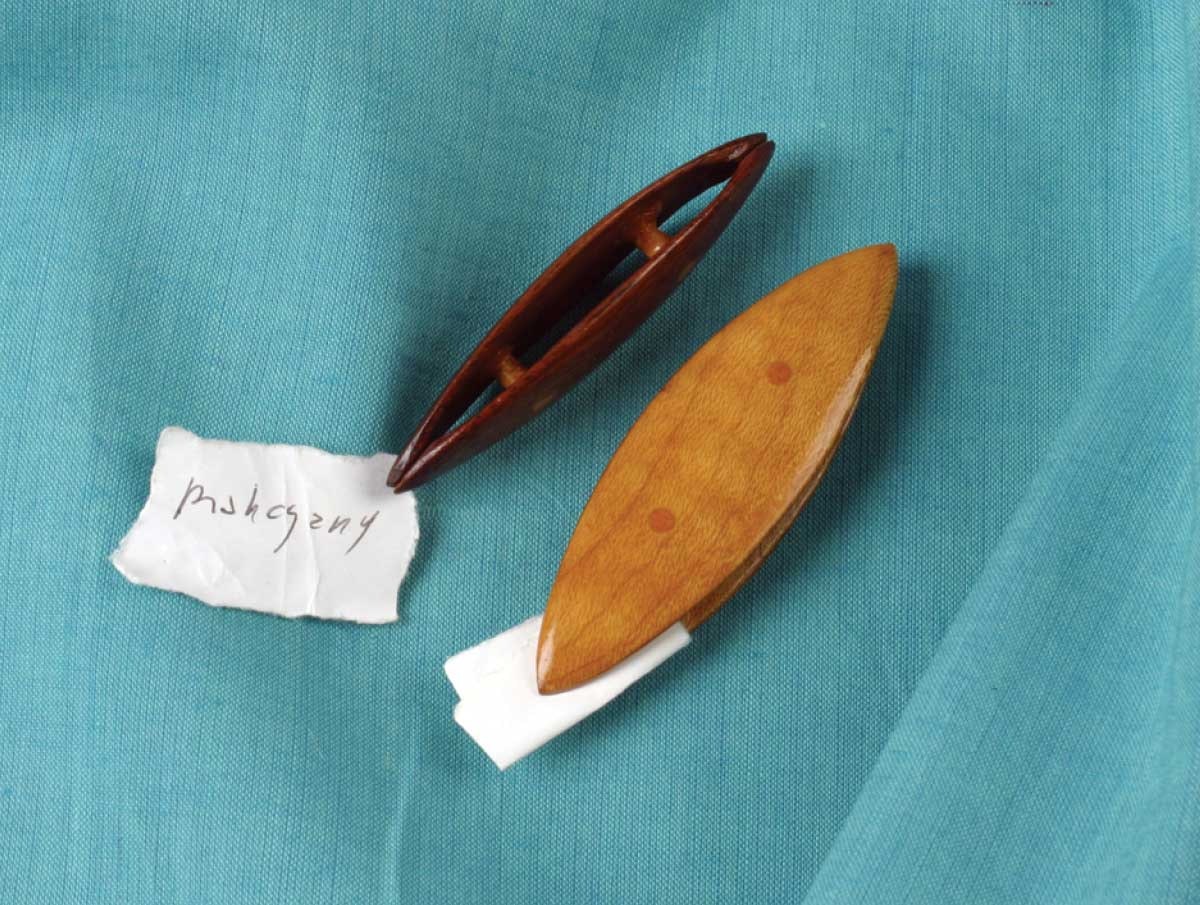

Two of the shuttles with the paper notes written by Anastasius “Tom” Nicolaides indicating the wood he used to make each shuttle. Photo by Jason Reid

Opening the package when it arrived was like Christmas. Each shuttle was in its own bag, and some had little paper notes in Grandpa’s handwriting identifying the type of wood used—woods such as mahogany, maple, and cherry. All work marvelously. I now own more than fifty of Grandpa’s tatting shuttles.

Several more of his shuttles have come up for sale online in recent years, but I am content to know that my grandfather’s creations will bring joy and satisfaction to new owners. In sharing my heritage and that of my family with other lacemakers across the globe, I feel that my grandparents continue to exist.

Mary Nicolaides is a second-generation lacemaker who has been active in the Rocky Mountain Lace Guild (RMLG) and the International Organization of Lace (IOLI). She has served as president of the RMLG and was cochairman of the 2005 IOLI convention in Denver. She is particularly interested in tatting, needle lace, lace history, and collections.

This article was published in the May/June 2008 issue of PieceWork, and this post was updated on September 16, 2020.