During the early 1930s, the author and textile enthusiast Florence Yoder Wilson (possibly 1888–1950) wrote a series of remarkable articles casting recent immigrants to America in a positive light; remarkable first because the preceding decade had been marked by the enactment of severe laws restricting immigration. Even more remarkably, the series was published in Needlecraft: The Magazine of Home Arts. Readers who anticipated a new quilt or crochet pattern may have been startled to find covers and articles praising the fine needlework and citizenship of the nation’s newcomers.

Needlecraft, published in Augusta, Maine, had taken its place in the magazine world in September 1909. Each month, the magazine sought to inspire and encourage the “wideawake [sic], sensible home-woman” who craved practical information about the home arts, especially needle-art patterns. Charter subscribers—the magazine claimed that thousands subscribed even before the first issue—dubbed the magazine “our little sister in white.”

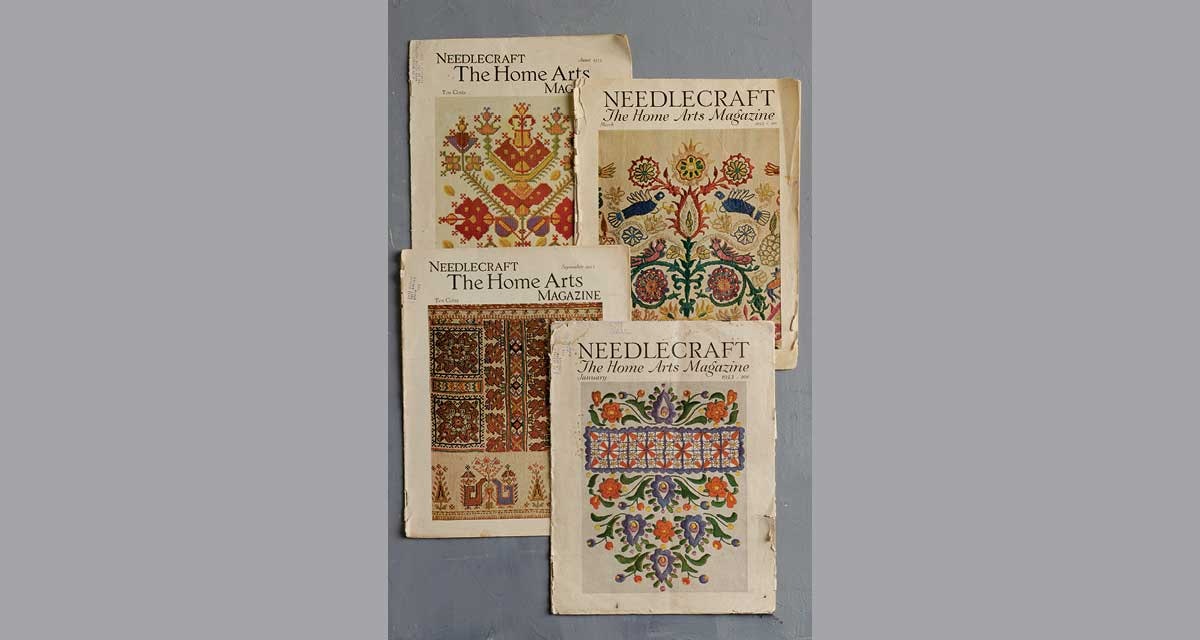

Needlecraft magazine covers, featuring needlework from various countries. Clockwise from top left: June 1933 (Syria), March 1933 (Greece and Turkey), January 1933 (Hungary), September 1933 (Bulgaria). Collection of the author, except for January 1933 collection of PieceWork. Photograph by Joe Coca

A glimpse into the complex history of American immigration law suggests that Needlecraft’s positive stance on immigration was bold indeed. After Ellis Island opened in 1892, the subsequent influx of millions of immigrants alarmed many native-born Americans. The powerful Immigration Restriction League, founded in 1894, blamed the nation’s increasing social ills on immigration and despaired of assimilating “new” immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe (in contrast to “old,” presumably acceptable, immigrants from Northern and Western Europe) into the fabric of American culture. The Dillingham Commission (House-Senate Immigration Commission, 1907–1910) also concluded that immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe threatened the stability of American society. Its findings provided support for immigration restriction laws, beginning with the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which limited annual European immigration to three percent of the number of people from a given country living in the United States in 1910, and culminating in the National Origins Formula of 1929, which barred Asians altogether and capped immigration at 150,000 annually.

Throughout the 1920s, readers counted on Needlecraft for inspirational sentiments about motherhood and the home arts, and cover art tended toward dainty needlework for home and family. Editors, however, delved deeper into social concerns that had crept onto the editorial pages and led the magazine into new territories. In June 1929, the editor, with near-breathless enthusiasm, announced the launch of an “innovative” series on the progress of needlework through the centuries. The cover depicted an Egyptian woman wearing characteristic regalia but with dubious weaving tools and techniques, and a feature article attributed to F. Y. W. extolled the contributions of Ancient Egypt to needlework. (“Tutmania” had gripped American popular culture ever since the discovery in 1922 and subsequent excavation of the tomb of King Tutankhamen.) The July cover and another F. Y. W. article explored the embroidery of Ancient Greece. August’s piece on medieval embroidery was credited to Florence Yoder Wilson, who would write all subsequent series for Needlecraft on historical and cultural themes, culminating in the America’s Heritage series. The editor did not spare the hyperbole about reader enthusiasm for the new covers and articles, which “demonstrate in a most delightful way, and indisputably that ‘all the world is needleworking!’ and somehow they serve to draw us nearer together—we women of one land, and women of another, enlisted in a common cause; they appeal to the hearts of us.”

Such praise no doubt encouraged Florence Yoder Wilson. She tackled Swiss bobbin lace; Irish crochet; Javanese batiks; Italian and Belgian lace; Czechoslovakian, Romanian, Greek, and Polish embroidery; and various needle arts of Sweden, Spain, and Russia. Not only did she elaborate on needlework techniques and aesthetics, Wilson placed needlework and traditional costume within political, geographic, and historical context. In March 1932, she explained:

In the course of preparing and writing this series it has been intended to attempt to show how closely the home arts are allied with the great world of which they are a part, and that although they may have been created in a sheltered and even restricted environment, sometimes by the hands of women who have never ventured outside of the limits of their home, that they nevertheless are closely bound up with the history, geography, art and literature of the country from which they spring.

Needlecraft introduced the America’s Heritage series in July 1932. Clearly, Wilson considered needlework an accessible means of encouraging international understanding and tolerance for America’s immigrant populations. Needlework and costume of other nations were exciting, and the immigrants themselves had much to contribute to the cultural fabric of the nation. “Our naturalized American citizens have not come to us empty-handed,” she wrote. “They have brought with them a dowry, this untold wealth of native handcrafts which have been growing for centuries in foreign lands.”

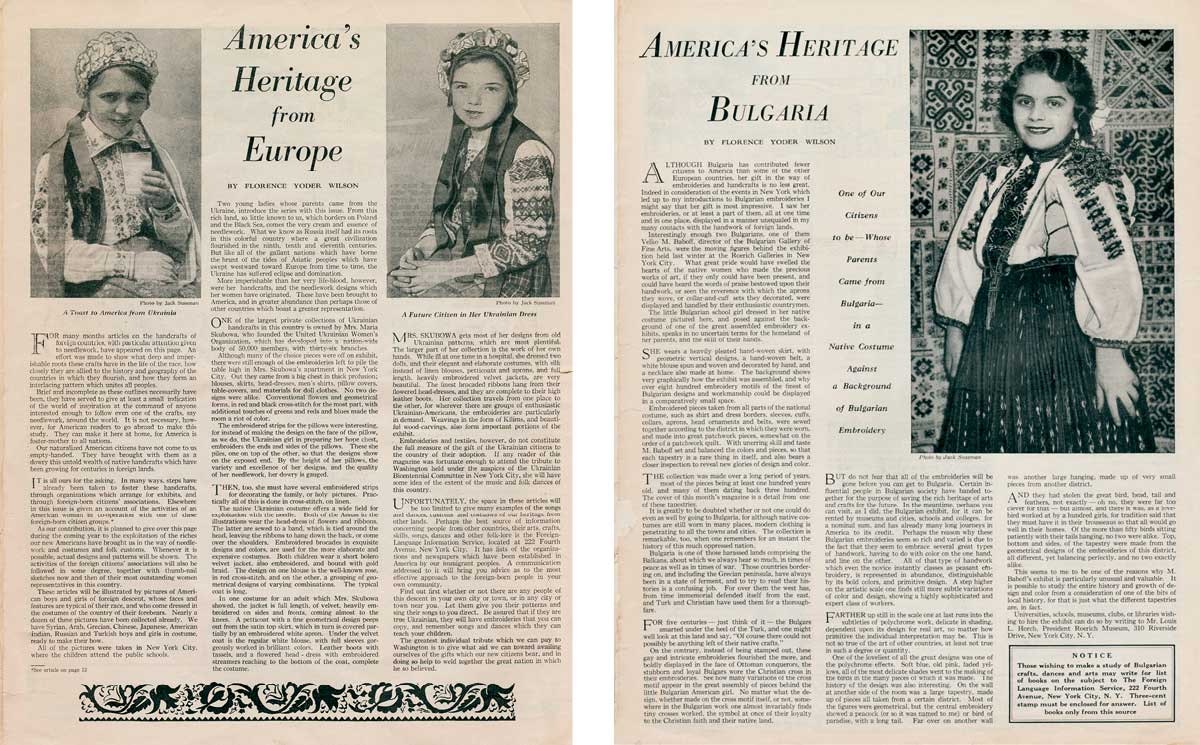

In the inaugural article of America’s Heritage, Wilson elaborated on the cross-stitch embroidery of the Ukraine, a “gallant” nation that had suffered “eclipse and domination” over the centuries. An exceptionally lovely illustration of a Ukrainian woman wearing a traditional embroidered shirt graced the cover. Wilson also established two key features for America’s Heritage articles. First, she guided readers to resources for further study available at public libraries, from immigrant organizations, and from the Foreign-Language Information Service. Second, she illustrated articles whenever possible with contemporary photographs of public-school children of “foreign” descent wearing traditional costume. Wilson detailed the intricate techniques and symbolism of their clothing, and captions called attention to American citizenship for these children: “A Future Citizen in Her Ukrainian Dress”; “Miss Czechoslovakia of America”; and “One of Our Citizens to Be Whose Parents Came from Bulgaria.”

Left: The page from the July 1932 issue of Needlecraft, featuring the first article in the America’s Heritage series written by Florence Yoder Wilson. Collection of the author. Right: The page from the September 1933 issue of Needlecraft, featuring another article in the America’s Heritage series written by Florence Yoder Wilson. Collection of the author.

Photographs of a schoolboy from Turkey and schoolgirl from Greece appear in Wilson’s article about Greek and Turkish embroidery (March 1933). Cautioned that she could not show these children on the same page because Greece and Turkey had been enemies, Wilson responded that “. . . the girl and boy are in America now and will in time be full-fledged citizens like the rest of us.”

Wilson had traveled in Europe during the summer of 1932, collecting textiles and stories. Of the ubiquitous and colorful embroidery of Hungary, she enthused, “Decoration in other countries seems meager after comparison with the Hungarian” (January 1933). Wilson examined the long history of Syrian and Russian handcrafts. She added that aristocratic women of old Russia who had fled to America during or following the Russian Revolution (1917) now served as sources for fine Russian needlework, “the very work we wish to foster and utilize for our own enrichment” (June 1933). Wilson was amazed that the intricate embroideries continued to flourish in Bulgaria, a much-oppressed nation of the Balkans (September 1933); the cover of that issue featured Bulgarian embroidery.

Wilson also celebrated renewed interest in American Indian cultures (July 1933). Despite their tragic history, Wilson assured readers, “Without crossing the ocean, within the confines of our own country there is material enough to keep us busy all the rest of our lives.” In a photograph accompanying the article, Good Eagle Voice, a New York City schoolgirl from the Winnebago Tribe in Nebraska, and Rolling Cloud, a boy from the Hopi Indian Tribe in Arizona, wore traditional costumes, although these were perhaps not authentic to their tribes.

Wilson’s additional articles for Needlecraft promoted the critical importance of education and international understanding. In 1935, writing as an “American Housewife Abroad,” Florence Yoder Wilson wrote her last Needlecraft articles, describing her European travels in search of traditional textiles. Home Arts: Needlecraft (the magazine’s title beginning in the late 1930s), however, was in decline. The number of pages had dwindled from nearly forty in 1929 to ten by July 1940; Needlecraft ceased publication by May 1941. Needlecraft was no longer a vehicle for Florence Yoder Wilson’s fearless ideas and opinions on needlework, immigration, and international understanding during a time of immigration restriction in America.

Florence Yoder Wilson

Apparently an intrepid traveler, Florence Yoder Wilson spared no expense or effort to find traditional textiles, especially needlework, while traveling. She found purses made from old Macedonian sleeves in Ragusa, Yugoslavia (present-day Dubrovnik, Croatia). She also traveled in the American Southwest.

Besides her articles for Needlecraft, she wrote on other subjects, including Russia: Means of Grace and Hope of Glory (New York: Lucis Press, 1941), a book of articles reprinted from The Beacon magazine. Yet none of her writings are accompanied by information about Wilson herself.

An Internet search reveals that Florence Elizabeth Jeffries Yoder was born to Jocelyn Z. Yoder (1848–1933) and Phoebe (or Phebe) Tallman Yoder (1853–1935) on August 6, 1888, in Kansas. She was the youngest of six children and the fifth daughter. Her father, according to his obituary in the Washington Post, had been a land agent for the Department of the Interior, and later was cashier of the House of Representatives during the administration of Grover Cleveland. After that, he worked for the Northwestern National Fire Insurance Company until his retirement. The 1900 and 1910 federal censuses show Florence living with her parents in Washington, D.C. The genealogical website that puts Florence’s birthplace in “Kansas (Garden City?)” also mentions marriage to Leigh Hunt Wilson (no date or place) and a divorce (no details). Another genealogy site has a long article on Jocelyn, a family photograph taken before Florence’s birth, and a note after Florence’s name that she “married a Mr. Wilson.”

The History of Bridgeport and Vicinity, Volume 2 (1917), has an entry for Leigh H. Wilson, son of James A. Wilson and Phebe Curtis Wilson. After being a reporter for newspapers in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, California, Colorado, and Illinois, Wilson worked for a time as managing editor of the Washington Times, leaving in 1915. At the time of the book’s publication, he was president of Bridgeport Y Plate Company, a manufacturer of printing plates.

The Find A Grave website has an entry for Leigh Hunt Wilson, born 1877, died February 2, 1926, buried in Newtown, Connecticut, about five miles from his birthplace of Sandy Hook. There is no mention of a wife or children and no photograph of him.

The Washington Post obituary of Florence Yoder Wilson’s father (1933) says that survivors include a son and three daughters, including Florence Yoder Wilson of New York; her mother’s (1935) says that she is survived by “Mrs. Florence Yoder Wilson, now in Geneva, Switzerland.” The obituary for her sister Bessie, who died in 1931, mentions a surviving sister, “Mrs. Florence Wilson, who resides in New York City.”

Several genealogy sites list the year of Florence Yoder Wilson’s death, 1950, but neither the day nor the month of death. The obituary of her brother, Jocelyn Paul Yoder, dated October 1, 1950, doesn’t mention her as a surviving sibling, so she seems to have died earlier that year.

Susan Strawn, formerly an illustrator and photostylist for Interweave, teaches dress history, cultural perspectives of dress, and surface design at Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois. A knitter herself, she is the author of Knitting America: A Glorious History from Warm Socks to High Art (Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2007) and a member of PieceWork’s editorial advisory panel. She thanks the Seattle Public Library and Museum of History and Industry (Seattle) for access to issues of Needlecraft in their collections and is grateful to the Seattle Public Library for the use of the Scandiuzzi Writer’s Room while preparing this article.

This article was originally published in PieceWork November/December 2012.