When Shakespeare coined the phrase “All that glitters is not gold,” he most likely did not have the jewel beetle in mind. But this particular beetle is not only shiny, it was also considered extremely valuable by those who coveted its luster and iridescence in early India.

Natural Glitter

The use of beetles’ wings as natural glitter for clothing and accessories was widespread throughout India during the Mughal Empire of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When India was colonized by the British Empire during the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, beetle-wing embroidery was appropriated and became a wildly popular fashion fad in England and America.

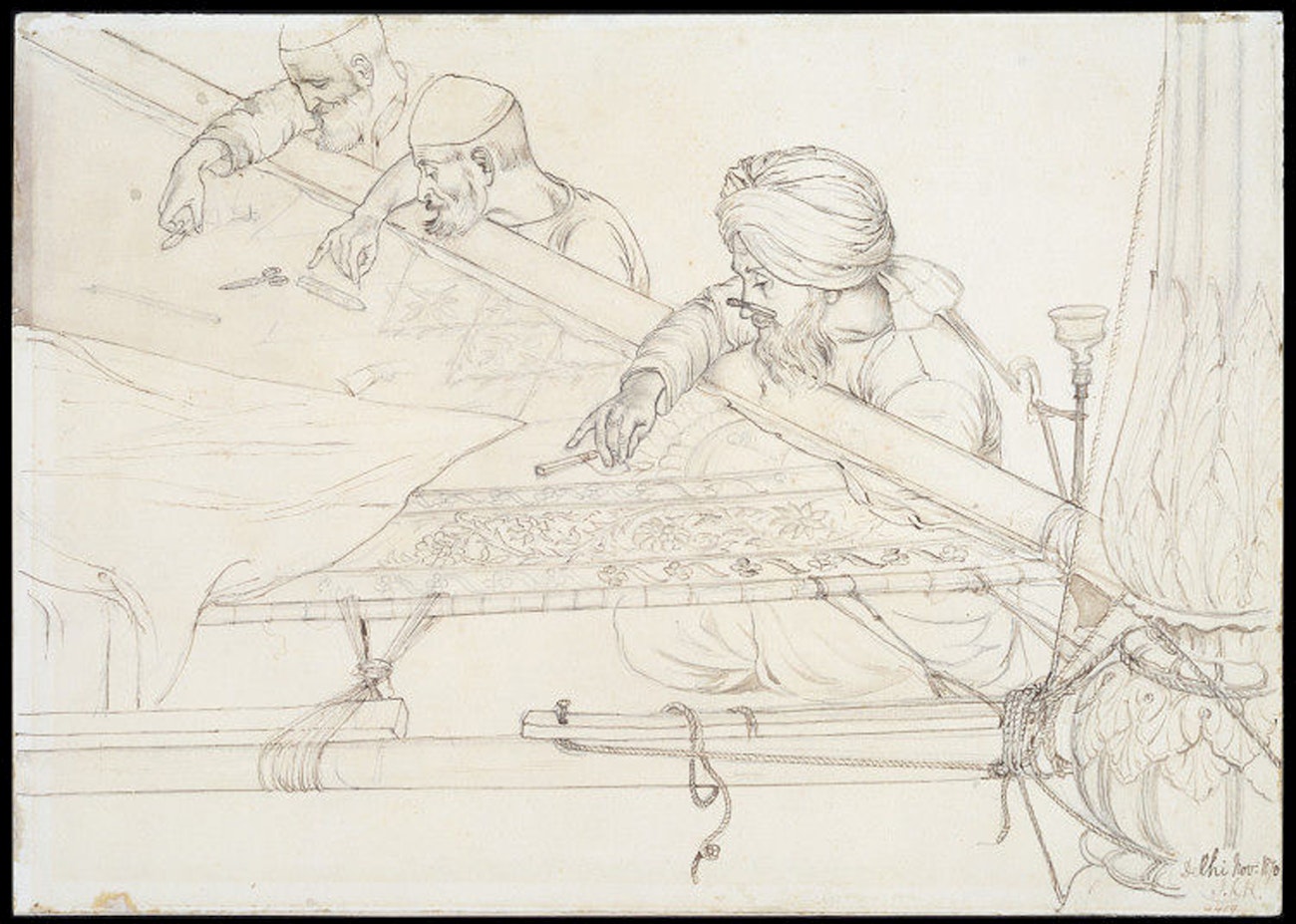

Zardozi embroiderers at work in 1870 India. Delhi Nov 1870 J.L.K 4419: On Verso, 30. Gold embroidery Delhi. J.L.KIPLING. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Zardozi embroiderers at work in 1870 India. Delhi Nov 1870 J.L.K 4419: On Verso, 30. Gold embroidery Delhi. J.L.KIPLING. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Indian Origins

During the rule of the Mughal dynasty, beetle-wing embroidery was used all over India for household textiles and personal garment adornment. The Indian style of beetle-wing embroidery used tiny pieces of the wing casing (elytra) as small features in overall designs and was often done on cotton or silk fabrics for men’s coats (jamas), turbans, and footwear; women’s fitted bodices (cholis) and saris; and children’s belts. Elite members of emperors’ courts enjoyed riches and luxuries of the highest order, which is where the craft likely reached new levels of opulence with one-of-a-kind pieces created specifically for their use.

Beetle Mania

Beginning around the year 1757 through the mid-1900s, India was colonized by the British Empire. Indian textiles were appropriated, with European visitors coveting the exotic, glittering splendor of beetle-wing embroidery. Soon, Indian embroiderers were creating elaborate beetle-wing work solely for export to European and American markets.

To keep up with demand, Indian makers began to create less intricate, more standardized designs geared toward fast-paced production. The work emphasized individual elytra in the overall designs, conforming to Westerners’ desire for beetle-wing embellishments to look like actual, live beetles. In many instances, elytra were embroidered onto cotton netting, most likely to increase its versatility for dressmakers abroad.

Black skirt, silk net with couched gold and java beetle-wing embroidery, Collection of Auckland Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, 1994.201, T1636. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Black skirt, silk net with couched gold and java beetle-wing embroidery, Collection of Auckland Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, 1994.201, T1636. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Heavy Metal

To create beetle-wing embroidery, makers used the wing cases of jewel beetles (Buprestidae family) that were specifically farmed for this purpose. The elytra were pierced with holes, cut into shape, and then sewn directly onto fabric or netting with overlapping threads to secure the pieces. Zardozi, a type of intricate embroidery using precious metal threads of gold and silver, was used to produce heavily ornamented patterns. Designs were built up using hundreds of whole elytra, elytra fragments, metallic threads, gold and silver foil strips, metal-wrapped silk threads, and gilt sequins to create an overall glittering effect.

Off-white cotton sheer ground with embroidered design of a stylized floral spray with two large blossoms and numerous small ones curving to the left. The vines are executed in gold foil strips, the small flowers in gilt sequins, and the leaves in beetle elytra. 1931-43-20. Collection of Cooper Hewitt Museum. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Off-white cotton sheer ground with embroidered design of a stylized floral spray with two large blossoms and numerous small ones curving to the left. The vines are executed in gold foil strips, the small flowers in gilt sequins, and the leaves in beetle elytra. 1931-43-20. Collection of Cooper Hewitt Museum. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Glitterati

Beetle-wing embroidery became a peculiar fad for high-society fashionistas who craved conspicuous clothing with which to announce their elite status. These spectacular garments were worn for special occasions such as presentation ceremonies, coronations, evening balls, and other social functions. Since they were not used for daily wear, the gowns themselves sustained very little wear. Many garments have survived and can be viewed in museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the West Highland Museum in Scotland, among others. Famous examples include garments worn by Ellen Terry for her Lady Macbeth costume (circa 1889), by Mary Jane MacDougall as a presentation gown (circa 1822), by Barbara Morrison as a gown for a social function (circa 1868), and by Lady Curzon for a coronation ceremony in India (circa 1903).

Lady Curzon wearing the "Peacock Dress" created for her in 1903 by the House of Worth (designed by Charles Frederick's son, Jean-Philippe Worth). This portrait completed posthumously in 1909 by William Logsdail following Lady Curzon's death in 1906. Oil on canvas by William Logsdail, 1903. Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

Lady Curzon wearing the "Peacock Dress" created for her in 1903 by the House of Worth (designed by Charles Frederick's son, Jean-Philippe Worth). This portrait completed posthumously in 1909 by William Logsdail following Lady Curzon's death in 1906. Oil on canvas by William Logsdail, 1903. Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. Image via public domain, Wikimedia Commons

The Enduring Allure of the Beetle Wing

Styles changed at the end of the nineteenth century, and beetle-wing embroidery fell out of fashion as the twentieth century approached, in part due to the weight of the metal embellishments. As we view these garments in modern times, we see the shiny part of an insect’s body on clothing disembodied from its previous wearer and maker. While we marvel at the countless hours of painstaking labor that went into the creation of these fabrics, we may also wonder how anyone would consider wearing a bug in any form, let alone hundreds of them all in one place. But the allure of the iridescent blue-green beetle wing lives on.

Resources

- Angus, Jennifer. “Nature’s Sequins,” Cooper Hewitt, September 14, 2018, www.cooperhewitt.org/2018/09/14/natures-sequins.

- “Indian Embroidery,” Victoria and Albert Museum, www.vam.ac.uk/articles/indian-embroidery.

- Libes, Kenna. “Beetle-Wing Embroidery in Nineteenth-Century Fashion,” Fashion History Timeline, July 28, 2021, fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/beetle-wing-19thcentury.

- “The Mughal Court and the Art of Observation,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/curriculum-resources/art-of-the-islamic-world/unit-five/chapter-four/introduction.

- Thomas, Nicola J. “Embodying Imperial Spectacle: Dressing Lady Curzon, Vicereine of India 1899–1905.” Cultural Geographies, Volume 14, Number 3 (July 2007), pages 369–400.

Marsha Borden is a writer, needleworker, and textile artist based in Connecticut. She enjoys researching and writing about historical textile techniques, materials, and makers. Find her @marshamakes on Instagram and at marshaborden.com.